Homegrown value

|

A measly $1.184 million accounted for a quarter of the victories that transformed the Colorado Rockies from also-rans to National League champions last season.

That’s how much the Rockies paid Troy Tulowitzki, Garrett Atkins and Brad Hawpe, the three gems who combined last year to make 5 percent of what Alex Rodriguez made in 2007. Along with the rest of the Rockies' pre-arbitration players, they accounted for more than half the team's 36 marginal wins – the number above the 54 that a team of replacement-level players is expected to accumulate.

And it's particularly telling when viewed through the payroll prism: The Rockies' $61 million was the fifth-lowest in baseball, showcasing the efficiency of building a first-rate scouting and player-development pipeline. The best farm systems can generate $30 million to $40 million in annual payroll savings – Matt Holliday, who added another five marginal wins to the Rockies, cost only $4.4 million as a first-year arbitration player – as well as unlock the huge revenues gleaned from playoff appearances.

The value of Colorado's devotion to developing from within was an estimated $25 million in 2007 payroll savings and another $30 million in future revenues from reaching the World Series.

No longer is hoarding prospects merely the domain of rebuilding franchises. The defending champion Boston Red Sox rank second in Baseball America's organizational talent rankings, the New York Yankees fifth and the Los Angeles Dodgers sixth. Every executive covets the ability to control a player for his first six years of major league service, especially the first three, during which pay is near the league minimum regardless of performance.

Look at the case of three shortstops from last season. The Atlanta Braves' Edgar Renteria accounted for 18 Win Shares, according to Hardball Times, and the Pittsburgh Pirates' Jack Wilson and Seattle Mariners' Yuniesky Betancourt each posted 19. Essentially, they were the same player. Yet Renteria earned $9 million under his long-term contract and Wilson made $5.25 million.

Betancourt? In his second big-league season, he made $400,000.

Two weeks ago, the Rockies signed Tulowitzki – a rookie last season – to a six-year, $31.6 million deal. They decided to forgo paying him near the minimum for two more seasons, as they had with Atkins, Hawpe and Holliday, and in turn bought out a year of the shortstop's free agency for $10 million, a bargain even now.

These days, this isn't rare. Over the past month, Curtis Granderson, Justin Morneau, Robinson Cano, Carlos Pena, James Shields, Yadier Molina and Nate Robertson also signed deals that will delay their free agency, and it's a reaction to evolution in the free-agent market. Three factors shape free agency: the rising cost of high-impact players on an open market, the reality that not all teams can afford free-agent talent and, in turn, the increased popularity of contract extensions to young stars.

Little has changed with high-revenue teams wading in the free-agent pool and offering whatever it takes to lure a key player – that elusive last piece of the puzzle.

Aggressive ticket price increases and the growth of team-owned regional sports networks have helped the high-revenue teams build an even stronger financial base. Also, the current labor agreement calls for a lower revenue-sharing tax rate, which means teams get to keep more of the revenue they generate from winning. Because the dollar value of each win increases, teams can justify spending more to improve their team.

A handful of teams have the revenue base and revenue growth from winning to justify compulsive shopping in the free-agent market. For less competitive teams, the cost of winning via free agency often exceeds the financial payoff from those victories. In 2007, Torii Hunter generated about four wins (above a replacement level player). Over the next five seasons, the Angels will pay him $18 million per year. If he stays healthy and his skills deteriorate modestly as he ages, Hunter will cost about $5 million (or more) per win over the length of his contract. The Angels can justify this steep price because they expect to stay a contender, meaning they expect Hunter's four wins to be of the highest value – ones that push the Angels into the postseason and the spoils that accompany it.

For an 80-win baseline team, adding four wins at $5 million per win would make little financial sense. Because an 84-win team has only a modest chance of reaching the postseason – based on recent experience, about 6 percent probability in the AL and 16 percent in the NL – teams would have little opportunity to recoup the investment.

Even teams that can afford to pay free-agent prices have realized that scouting and player development provides a cheaper path to procuring talent.

This makes the signings of Tulowitzki and Granderson (by the Detroit Tigers) all the more understandable. As long as other teams continue to lock up their young players, it will reduce the flow of impact players into free agency. A reduced supply will put further upward pressure on free-agent prices. And so begins the cycle once again.

The smartest teams have figured out the inefficiencies of the free-agent market and try to, at the very least, balance them with the challenges of creating a strong player-development system. One way to measure the financial value of internally developed players is to compare their cost – signing bonus, development and the salary over the first six years of major-league service – to the cost of purchasing the same level of performance in the free-agent market.

Take, for example, the Milwaukee Brewers, who have excelled at developing talent under general manager Doug Melvin and scouting director Jack Zduriencik. The Brewers, who led the NL Central most of the season, sported homegrown, pre-arbitration players at nearly every position. Prince Fielder, Ryan Braun, Corey Hart, J. J. Hardy, Rickie Weeks, Yovani Gallardo and Carlos Villanueva were all key contributors.

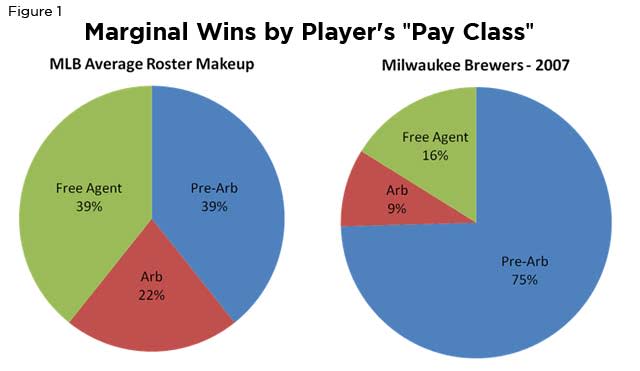

The Brewers' pre-arbitration players accounted for 21 of the team's 29 marginal wins, and for them, the Brewers paid $4.4 million in salary. The average 83-win team would have generated only about 11 marginal wins from its pre-arbitration players. (See Figure 1)

On a typical MLB roster, the 10 extra wins would have been divided between free agents and arbitration-eligible players. And, according to an analysis by Dave Studenmund at Hardball Times, the average cost of a marginal win in the free-agent market for 2007 was $5.3 million, compared to $2.5 million for arbitration-eligible players and $52,000 for pre-arbitration players.

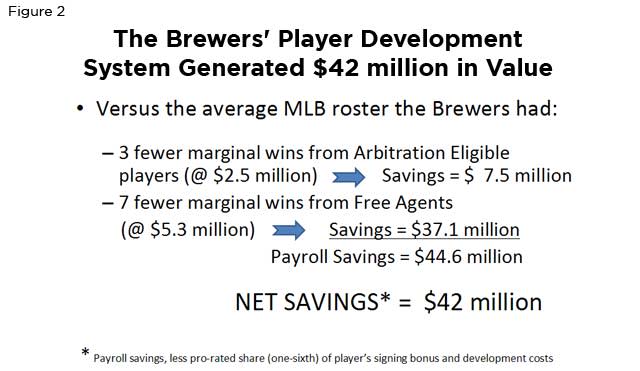

From the standpoint of the cost of a marginal win, Milwaukee's superior scouting and player-development system saved more than $44 million in salary. Even adding back a pro-rated share of the $9.9 million in signing bonuses and $2.25 million of player development costs, the value of player development to the 2007 Brewers was $42 million. (See Figure 2)

Of course, developing prospects who turn into genuine major-league ballplayers is an inexact science. No team wants to handicap itself with a thin system.

No team has to, either.

Maximizing the value created by player development takes three tactics, the first of which is a commitment to high-value positions. The free-agent market consistently prices pitchers above position players when it comes to annual salary and length of contract. Barry Zito, not even a league-average pitcher last season, is one year into a seven-year, $126 million deal. The Chicago White Sox gave reliever Scott Linebrink $19 million for four seasons this winter. Similar examples can be found all over baseball.

Much like a farmer who considers the market for his crops when he decides how to allocate his acreage, MLB teams need to bias their development resources toward the highest-value positions – primarily pitching – when scouting, drafting and signing key prospects. Harvesting a Mark Mulder-type lefty starter from your farm system versus an equally talented second baseman – say Orlando Hudson – would create $5 million to $10 million more value annually. Especially when the alternative is replacing the performance in free agency.

The next step deals directly with the draft: ignoring the slotting recommendations designed by MLB to keep a lid on signing bonuses for early-round draft picks. Some teams, such as the Houston Astros, heed MLB’s scale – and now they have perhaps the worst farm system in baseball.

By failing to sign top prospects, teams miss the chance to capitalize on the single lowest-cost source of future major league talent – the draft. The Detroit Tigers, habitual slot ignorers, have gone over slot for Cameron Maybin and Andrew Miller (who netted them Miguel Cabrera and Dontrelle Willis), and in June chose Rick Porcello, the right-handed high school pitcher compared to Josh Beckett, with the 27th pick. Porcello slipped because of bonus demands. Detroit didn't blink and paid him $7 million to sign.

If Porcello ultimately develops into even a No. 4-level starter, he will save the Tigers millions of dollars.

Bonuses are even cheaper in Latin America, the third key to building a farm system. With players there signing at 16 years old, it’s a daunting task to project their development. Yet the pricing allows for high risk. In 2007, Boston signed the most coveted player in the Dominican Republic, Michael Almanzar, for $1.5 million, while the Yankees doled out $3.25 million in signing bonuses to four of the top 10 prospects. Although signing bonuses have escalated dramatically over the last five years in Latin America, a top international signing likely is a worthwhile, albeit speculative, investment.

Beyond the financial savings, player development adds intangible value to a franchise. The Internet allows fans to closely monitor their team’s minor-league system, thereby establishing a connection to potential stars long before they set foot in a major-league ballpark. Such connections help build fan loyalty and commitment to not only the player but also the team – and the knowledge that the player likely will wear the same major-league uniform for at least six years only enhances that.

Because for whatever a store-bought counterpart brings to a team, strong player development is the lifeblood of a team – on the field and in the books. Developing talent internally and reaping the financial benefits from the pre-free agency years is the most efficient, low-cost way to assemble a roster.

The economics of the free agency virtually guarantee it.

Vince Gennaro is a consultant to several Major League Baseball teams and the author of "Diamond Dollars: The Economics of Winning in Baseball," an innovative look at the business of baseball. This followed a 20-year career at PepsiCo, where he was president of a billion-dollar division. Gennaro teaches a graduate course on the business of baseball in the Sports Business Management program at Manhattanville College.

Send Vince a question or comment for potential use in a future column or webcast.