Piniella to make a bittersweet farewell

Over the years, Lou Piniella's fire faded into a few crackling embers. He announced his retirement effective season's end Tuesday, beaten down by the most unforgiving job in baseball. Managing the Chicago Cubs changes a man, and it turned Lou Piniella from belligerent of the highest order to colicky grandfather.

To shoulder a century of failure takes a person of great strength, and not even Piniella was up to the task. The Cubs haven't won a World Series since 1908. Whoever takes over will be the team's 50th manager since the championship. Each previous one hoped to be the savior, though few came with the pedigree – the playing chops, managerial experience and unfettered ability to slay people with the might of his tongue – of Louis Victor Piniella.

He was hope. He is failure.

What Piniella embodied when the Cubs hired him – a whip-cracking, name-taking, dirt-kicking firebrand – no longer exists. Resignation gripped his face. He hasn't really blown up at an umpire in more than three years. He is 66. The energy escapes him. So Mt. Lou lay dormant as his teams faded into irrelevance.

Which is a shame, because what made Piniella such a force never was his tactical aptitude or his nurturing of players. Piniella was one of the last great intimidators. In his formative days, he would intimidate players, berate them or, in the case of Rob Dibble, fight them. He was angry and out of control and brought elegance to the umpire argument that little Earl Weaver never could.

Piniella wielded his temper with the dexterity of a fencer, and the sheer possibility of him blowing up was worth the price of admission to a game for any of the five teams he managed. Lou-clear explosions never took much. Maybe a bad call at a base. Perhaps a tight strike zone. Sometimes even less. Whatever the case, when Piniella lit the wick, off he went, never, ever quietly, and his June 2, 2007 rant embedded itself in YouTube history.

Spinal surgeons one day will study how Piniella so fluidly rocked his head back and forth as spittle jumped from his mouth to umpires' faces in the midst of a fit. He was a human bobblehead. If it wasn't his signature move, the various applications of dirt – kicked onto umpires or piled onto home plate – qualified Piniella for an honorary degree in soil science.

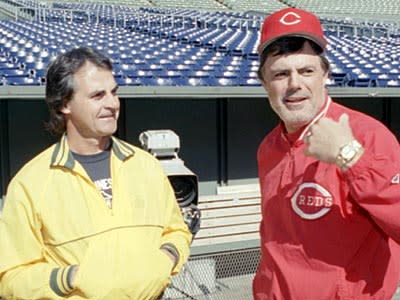

Surely Piniella would prefer his legacy consist of more than a temperament that befit a petulant child, and it does. He won two World Series with the Yankees as a player and managed the 1990 Cincinnati Reds to another championship. The 116 regular-season victories his 2001 Seattle team put up will be nearly impossible to top. Piniella has 1,826 wins as a manager, 14th most in history. Nine ahead of him are in the Hall of Fame. Tony La Russa, Bobby Cox and Joe Torre will be there. Only Gene Mauch isn't, and his winning percentage was .483. Piniella's is .519.

Never will winning be the thing with which Piniella is most associated, though, because he couldn't complement the Cincinnati title with one in Seattle and, particularly, Chicago. Nine Hall of Famers tried since Frank Chance led the Cubs to a championship. None succeeded, though Ryne Sandberg might be next in line. P.K. Wrigley, so desperate for something that worked, tried rotating managers in 1961 and '62. Sorry. The Cubs have searched and searched, pined and pined, and they really believed Lou was the one.

Only the job wore on him. His belly distended. Bags formed under his eyes. It wasn't some sort of mystical curse rendering itself on Piniella. It was a team that Piniella mismanaged in 2007 – remember when he yanked Carlos Zambrano(notes) after 85 pitches to save him for Game 4 of the NL Division Series? – blew its best chance with a first-round flameout the next season and woefully underachieved last year. Today, the Cubs are 42-52, saddled with more bad contracts than Freddie Mac, in the sort of purgatory teams dread.

Rebuild or retool? The middle remains possible because Chicago is a big-revenue team that can spend its way out of misery, though giving $136 million to Alfonso Soriano(notes) and $91.5 million to Zambrano and $48 million to Kosuke Fukudome(notes) doesn't exactly engender faith in management's ability to spend such largesse wisely.

Someone, sometime, somehow is going to take the Cubs and make champions of them. In a game whose economics have nearly eradicated the middle class, the Cubs are on the side of the haves, and their resources are too plentiful to deny that a GM and manager will find the formula that continues to evade the North Side.

On that day, somewhere on a golf course or at a bar, Lou Piniella will celebrate. Everyone who sits on the bench at Wrigley Field and calls the shots wants the Cubs to win. They were all hope, and they were all failure, and such a cycle deserves breaking.

Until then, Piniella gets to savor 68 games as a lame-duck. His farewell tour should include huzzahs and ovations. Piniella is a fading breed in baseball: the character. His fights, his mannerisms, his malapropisms – few are as good for an unintentional laugh as Piniella. He doesn't mind chuckling at himself, either.

So it doesn't seem too much to request one more eruption. Picasso found neo-expressionism in his later years. Mozart wrote the Magic Flute before he passed. While he couldn't bring Chicago a World Series, Lou Piniella, artiste of the argument, can summon up the strength to kick his hat and throw a base one final time, a fitting send-off for an unforgettable baseball man.