Allred's basketball journey takes new path

Lance Allred’s memoir of his journey to the NBA has received critical acclaim.

(HarperCollins)

One more summer league training camp, one more round of false promises and exaggerated hope, and Lance Allred(notes) found himself on the Orlando Magic's bench honoring the final days of a useless July commitment. As the deaf son of a polygamist colony, the most improbable 7-foot prospect, an NBA front office had once more underestimated his abilities.

"I will just say this about the end in Orlando: Some people don't understand that because my hearing is impaired, I'm really, really good at reading lips from even across the gym," Allred said. "With some of these [team executives], it's just like you're in high school again with all the cliques, the way that they talk about you. I've seen this all before, except now the kids have millions of dollars."

Even before this summer, a painful process of self-examination had taught one of basketball's most fascinating journeymen the cruel truths of his life. From a childhood in a Montana utopian commune to the twisted psychological abuse of ex-Utah coach Rick Majerus, Allred had spent too much of his life chasing the validation of false prophets. He had spent much of his identity pursuing the hallow validation of everyone else.

And with the insecurities of his 75 percent hearing loss – with an obsessive-compulsive disorder – Allred was forever an easy victim, an easier target.

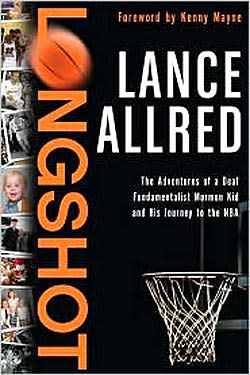

At 28 years old, he has been chasing the NBA so hard, for so long, and he even reached it with two months on the Cleveland Cavaliers' roster in 2008. He hasn't just authored one of basketball's most remarkable young lives, but a moving and funny memoir, "Longshot: The Adventures of a Deaf Fundamentalist Mormon Kid and His Journey to the NBA," which was published in May.

The book has been met with critical acclaim, but mostly it has been cleansing, liberating. Allred has had a dark, confusing journey. In a sport of stereotypical actors, where owners and executives, coaches and players, can be easily compartmentalized, Allred defies it all. His first book is on the shelves and a second manuscript is nearly completed: historical fiction on the 14th century Teutonic Knights in Germany. No, Lance Allred doesn't make the bus trips through the NBA D-League with an Xbox in his bag.

"They fought in the Baltics, a bunch of bad-asses," Allred said of his latest subjects.

Allred never would've considered himself one of those, but his staying power, his resiliency, have proven him so. He survived as the grandson of Mormon royalty – a descendent of Rulon C. Allred, the prophet of the fundamentalist sect. He survived three years with Majerus, whose relentless abuse included declaring Allred a "disgrace to cripples" and telling him he had "weaseled his way through life using his hearing [loss] as an excuse." Allred said Majerus tortured him in ways overt and subtle, pushing him to the brink of a nervous breakdown and ultimately post-traumatic syndrome. Majerus denied saying such things and was cleared of discrimination after a university investigation, but he resigned shortly after Allred's revelations were made public in 2003, citing health problems.

"That took me a long time to get over," Allred said. "I've owned up to my own shortcomings at Utah. Had I been more emotionally healthy and got some help, I might have been better prepared to handle something that nobody should ever have to endure. It seems so absurd now, but I was looking for a prophet to lead me. I wasn't comfortable with myself and got myself into a bind.

"But in turn, I give Majerus no credit for my success. I've learned to combat it all, but every now and then, I still have a nightmare about him where I wake up in a cold sweat and then I just think, ‘Thank God I'm not playing for him anymore.' "

Somehow, Allred found a way to marginalize his deafness as a disability on the basketball court. In his mind, he's had bigger hurdles. And, after all, most players have liabilities. They don't shoot well. Or handle the ball. Or defend. "In the fourth quarter, everyone is deaf," he said. "No one can hear anything. And I think that puts me at an advantage in the environment where a lot of guys get rattled. It allows me to be calm."

Allred became a two-time All-Star in the D-League for the Idaho Stampede, but he has grown weary of chasing the NBA grail on a $30-a-day per diem. He's returning this month for a second tour of European duty, securing a solid six-figure deal in Napoli, Italy. His game has been always more finesse than force, which even he admits might be best suited for Europe. "I'm done trying to figure it out here, done stressing out," he said. "I've had enough of playing along with this charade. I'm going to go where the money is, play and have some fun. I'm done fighting the powers that be here in the NBA. I'm done trying to prove my worth to these people."

It isn't so much bitterness as it is a sense of exasperation. Nevertheless, Allred is a European history major dying to see Italy. He'll keep playing and keep writing. Eventually, he'll go back to school, get his Ph.D. and teach college history in a small town. He's always gathering material, always finding his voice. Between now and then, he thinks about marriage and family, about religion and spirituality.

"I have a clear idea of what kind of family I want, and the kind of parent I want to be for my kids," he said. "I don't want them growing up in a society, like I did, where the guilt and fear is the strongest motivating factor. I want to take my kids to every church in the valley and let them decide for themselves what fits. My feeling on religion is this now: I don't need someone between me and God to mediate.

"With all the places I've been, all the things I've seen, how can any one man tell me if I'm living my life right? It's a big world out there, and the best you can do is learn from your mistakes and your flaws, and make sure that you pass that down to your kids."

He has chased the bouncing ball a long way, through the dark, and always, always, through the silence. For Lance Allred, the floor's finally wide open.