A gamer and a giver, taken away too soon

Her dream, she told friends, was to become a baseball general manager, which was a long way from where she started out in the game, as a ballgirl for the Seattle Mariners.

Her inspiration, she wrote on her blog, was Jackie Robinson. "Just as Jackie Robinson once said,'' she wrote, 'A life is not important except for the impact it has on others' lives.' ''

Rosie Santizo and Edgar Martinez.

(Special to Yahoo! Sports)

Rosie Santizo's gifts were abundant, said Mariners broadcaster Rick Rizzs, his voice catching as he struggled to describe the void left by her death at age 29. She taught English and life skills to Latin-born players for the Red Sox, Orioles and Mariners, and was a self-taught artist who wowed people with her pen-and-ink drawings of ballplayers. But Santizo was more than a couple of lines on a résumé.

"You know how you encounter people who say they want to make a difference?'' Rizzs said. "Well, she went out and did it.''

Santizo was killed in a car accident in Jordan, evidently as she was returning with friends from a visit to the Wadi Rum, a desert landscape of breathtaking rock formations. She was between semesters of a year-long exchange program in Kuwait, her grandfather Don Lovitt said, as part of her studies at the University of Washington. She'd gone back to school and was studying Arabic, but even as her life veered in a different direction, she had not abandoned her passion for baseball.

"I don't think Rosie ever turned that page,'' said her grandmother, Polly Lovitt.

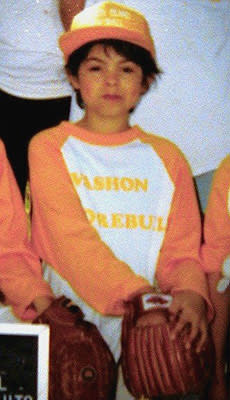

Rosie was born in Guatemala City and moved with her mother, Maria, and father, Mike, to suburban Seattle as a child. She grew to love baseball listening to radio broadcasts with her father, who was legally blind. Her grandparents have a photo of Rosie, no more than 7 or 8, posing in her Little League uniform.

Santizo in her Little League uniform.

(Special to Yahoo! Sports)

Mariners fans at the Kingdome were introduced to her passion during her teen years as this left-handed ballgirl who thought nothing of diving with abandon after foul balls – and at least one fair one. That was the one that made it onto the TV highlight reels; Rosie, 19 at the time, going airborne to field a drive by Craig Grebeck. "In midair,'' she said afterward, "I was so fired (up)."

Grebeck was awarded a ground-rule double. Rosie became a fan favorite. "When she was first hired as a ballgirl,'' Rizzs said, "she was so excited to be on the field, so excited about doing a good job. She went after balls like (Ken) Griffey going over the wall.

"She loved her job. She loved the fans.''

And they loved her back. One Seattle cop, Eric Mitchell, used to walk her down to the ferry each night from the Kingdome to make sure she got home safely to Vashon Island. "That touched us deeply, to hear of that,'' said Polly Lovitt, whose son, Bryan, married Rosie's mother, Maria, after her divorce.

Talented? One day Rosie picked up a pencil and sketched a drawing of Mariners star Edgar Martinez that was striking in its resemblance. Soon, orders came in for more, and she eventually was licensed by the players' association to market her sketches.

"I still have drawings she did of Dan Wilson and Edgar Martinez,'' Rizzs said. "She was gifted, and I mean gifted. I went to see her in a high school play in Vashon Island. She was the star of the show. She had the audience eating out of her hand. She was absolutely brilliant. I wasn't surprised. That was Rosie. Everything she did, she put her heart and soul in it.''

While in the Middle East this summer, Rosie reached out to Dan Duquette, the former general manager of the Montreal Expos and Boston Red Sox, who is trying to develop a baseball league in Israel. "She called me the last week of August,'' Duquette said. "She wanted to get together, but we didn't connect. I think she was having some kind of passport problems.''

In Duquette's office, he still has a copy of the orientation program Rosie developed for the team's Spanish-speaking players after he hired her to work for the Red Sox. He had jumped at the chance to do so when he noticed that she spoke both English and Japanese; at the time, the Red Sox were sharing a complex in the Dominican Republic with a Japanese team, the Hiroshima Carp.

"She was full of life, that kid,'' Duquette said. "She really helped a lot of those kids, not only with learning the language, but teaching them the skills they needed to make the transition to their new life – how to order meals, pay bills, how to do their laundry. She nurtured those kids, encouraged them.

"She taught them the skills that gave them the confidence to come to the States. And she was very positive. She never criticized them.''

Raquel Ferreira, the Red Sox director of minor league administration, remembers that wherever Rosie went during spring training, she wore her glove. "She was ready to play catch with anyone who asked.''

Felix Maldonado, a player consultant who has spent more than four decades with the Red Sox, much of his time with the team's Latin players, remembers those games of catch.

"She was a very, very smart lady,'' he said. "She was very aggressive, very enthusiastic and well respected by all of our players. She loved baseball. Sometimes she kept score for us in the rookie league games.'

While in the Dominican Republic, she also did some volunteer work for Esperanza International, the foundation run by former Mariners catcher and broadcaster Dave Valle that has granted thousands of small loans to impoverished Dominicans and Haitians, mostly women, looking to start or expand a business. When Valle began a similar program in the U.S., the first Latina he gave a loan to was Rosie, to assist her in her artistic endeavors.

She was thrilled when one of her former Red Sox pupils, Hanley Ramirez, won the National League Rookie of the Year award last season, and another, Anibal Sanchez, threw a no-hitter, even though both players accomplished the feats with the Florida Marlins.

"She was a great person and I'm very sad to hear the terrible news about the accident,'' Sanchez said in a message conveyed by Matt Roebuck, the Marlins' publicist. ''She really helped all of us as our first English teacher, and was a good friend as well."

Rosie later went on to run a similar program for the Orioles, then worked again with the Mariners when she returned to school to Seattle. One of her prized pupils was Yuniesky Betancourt, the team's young Cuban shortstop.

"One day she and Yuniesky were walking down the hallway toward me,'' Rizzs said. "I said, 'How you doing, Yuni?' I expected a nod or something.

"He hesitated, then said, 'I'm very fine, thank you very much.' I said, 'Nice job with the English, Yuni.' Rosie was very proud.''

Tom DeVries, a science teacher at Vashon Island High, once wrote a letter of recommendation for Rosie. "She seems intent,'' he wrote, "on squeezing several lifetimes out of one."

No one ever imagined she'd be given so little time to do so.

When word of her death reached the Mariners, a moment of silence was held for her at Safeco Field. On Saturday night, friends and mourners will gather at the Salavation Army temple in Seattle to remember her.

"What a loss,'' Rizzs said. "What a wonderful young lady.

"I still can't believe she's gone. I refuse to believe it.''