The worst owners in pro football history, from George Preston Marshall to Dan Snyder

Now that soon-to-be-former Washington Commanders owner has agreed in principle to sell the team to a group led by Josh Harris and includes basketball legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson, the NFL will have to look around for a new worst owner. Snyder, who experienced more team names (three) than playoff wins (two) in a tenure that started in 1999, was absolutely horrible, and you’ll see all the reasons why in a minute.

Not that Snyder is the only horrible owner in the history of professional football. It stands to reason that for every great owner over time, there have been those individuals who were in no way qualified to be in control of any franchise. Whether it was due to financial issues, the ego to believe that personnel decisions should be theirs and theirs alone, or just general incompetence and personality issues, there are those people who have controlled pro football teams when they had no qualifications to do so.

Here, for your consideration, are the worst owners in the history of professional football.

Harry Wismer, New York Titans

(Darryl Norenberg-USA TODAY Sports)

The American Football League was an unstructured mess in its early days, and nobody better personified the league’s tenuous hold on the sporting public than Wismer, the longtime sports broadcaster who became one of the AFL’s original “Foolish Club” when he got the New York Titans off the ground in 1959 for the inaugural 1960 season. The Titans weren’t actually a bad team in their early days — they posted 7-7 records in their first two seasons under head coach Sammy Baugh — but Wismer never had a chance to keep the team. The Titans were competing with the New York Giants for Market share, they played in the decrepit old Polo Ground, and Wismer didn’t have the money to deal with the realities of team ownership. Players and coaches used to have to race to the one bank and the one teller in the city that was authorized to cash their checks before the money ran out.

Eventually, terrified that they’d lose the team in the country’s most important market, the AFL in general set it up so that talent agent Sonny Werblin could buy the team, despite Wismer’s objections. Werblin made the team a serious endeavor with the hiring of head coach Weeb Ewbank and the signing of Joe Namath, and the New York Jets shocked the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III. Without the transition from Wismer to Werblin, the AFL may never have grown to the point where it could be taken seriously enough to force the 1970 merger with the NFL.

Robert Irsay, Indianapolis Colts

(Indy Star-USA TODAY NETWORK)

The gentleman seated to the right of Robert Irsay, with an expression on his face that brings to mind Mike Huckabee’s dog, is Jim Irsay, Robert Irsay’s son, and the Colts’ current owner. Jim Irsay took over the team after Robert Irsay’s death in 1997, but he — and everybody else in the Colts’ orbit — had to deal with a lot before that transition could happen. Irsay purchased majority interest in the Los Angeles Rams in 1972, then traded the team to Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom in an even swap, so things got off to an odd start.

Irsay was famous for berating his coaches and players. He fired head coach Howard Schnellenberger eight after a loss to the Philadelphia Eagles in 1974 because Schnellenberger wouldn’t change quarterbacks in the game. Irsay’s verbal abuse of his players after a 1976 preseason loss to the Detroit Lions led to head coach Ted Marchibroda’s resignation. After players and coaches threatened to walk away from their jobs, Marchibroda was re-hired. Players were treated horribly in contract negotiations, coaches were constantly second-guessed, and eventually, Irsay moved the team to Indianapolis after the city of Baltimore passed a law that would allow the city to seize the team under the rule of eminent domain.

It was never not a circus.

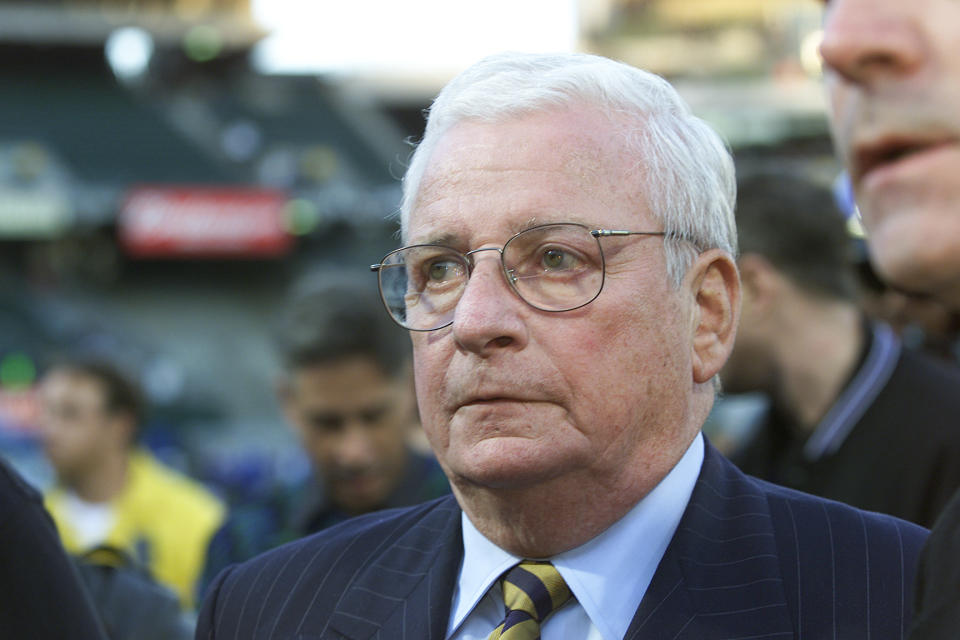

Art Modell, Cleveland Browns/Baltimore Ravens

(Brian Bahr/ALLSPORT)

Modell bought the Cleveland Browns in 1961 for $4 million, using only $250,000 of his own money to do so. It was a good investment, though made less so after he committed the cardinal sin of firing Paul Brown in 1963 from the franchise that bore his name after several disagreements about the direction of the franchise. The Browns did win the NFL championship in 1964 under replacement Blanton Collier, but that was the last championship they’ve ever won.

Modell’s decision to move the Browns to Baltimore in 1996, turning them into the Ravens, set off a rash of new stadiums around the NFL as other cities were informed by Modell’s performative example, but it’s hard to reconcile Modell’s dissatisfaction with the Cleveland situation when he was making money from his own team’s use of Municipal Stadium as well as renting it to the Cleveland Indians — at least, until the Indians became unhappy with their side of the deal. In 2002, financial issues with the Ravens had the NFL taking steps to have Modell sell the team to Steve Bisciotti in 2003.

Leonard Tose, Philadelphia Eagles

(Darryl Norenberg-USA TODAY Sports)

Tose was one of 100 investors to take partial ownership in the Eagles in 1949, paying $3,000 for the privilege. He tried to take a more prominent interest in the franchise over the next two decades, finally buying the team outright for $16,155 million, which was then the most ever paid for a professional sports franchise. The Eagles were an absolute disaster at that point — in 1968, the infamous incident where fans threw snowballs at a man in a Santa Claus suit on the field came about because fans were so frustrated with the team not only finishing 2-12, but winning two of their last three games and thus eliminating the opportunity to take O.J. Simpson with the first overall pick in the 1969 draft.

Tose did do a lot to improve the franchise, including and especially hiring former UCLA head coach Dick Vermeil in 1976. But Tose’s gambling debts were massive and well-known, and he eventually had to sell the team in 1985 when it all came due. Tose owed more than $25 million to Atlantic City casinos, and overall, his losses totaled somewhere between $40 and $50 million.

Daniel Snyder, Washington Redskins/Football Team/Commanders

(Brad Mills-USA TODAY Sports)

Where do we start with this guy? The constant meddling with coaches and general managers? The toxic environment in the building due to Snyder’s participation in a culture of sexual harassment and emotional abuse? The insistence for years that he would not change the “Redskins” name despite that fact that he had to know just how hurtful it was to so many people? Maybe it’s the fact that Snyder allegedly threatened to make public dirt on other owners were he forced to sell the team?

It’s all part of the recipe, and quite frankly, the NFL will be a far better organization without Snyder’s involvement in it.

George Preston Marshall, Washington Redskins

(AP Photo)

That said, Dan Snyder is not the worst owner in the history of the franchise he’s steered into the dirt for a quarter of a century.

That “honor” belongs to George Preston Marshall,

Why? For one reason and one reason alone” Marshall was the force behind the NFL’s ban on Black players from 1934 through 1945. Not that he was the only team owner who green-lit it, but he was the starting point for one of the most disgusting actions the league has ever taken. The few Black players in the league were summarily drummed out, and for over a decade, we were denied the talents of some of football’s best players of the era because of this racist nonsense. Marshall refused to integrate the Redskins (yes, he also coined the team name) until the early 1960s under serious pressure from Stewart L. Udall, JFK’s Secretary of the Interior, who found Marshall’s lily-white team just as insulting as it was. It wasn’t until Marshall was told in no uncertain terms that he couldn’t have the federal land he wanted for a new stadium that he finally bent.

Even after that, Marshall wasn’t above making a noxious point at the worst possible time. At one team meeting during the Redskins’ annual preseason jaunt through the South, the song “Dixie” began to play in the room. The entire team stood for the de facto anthem of the Confederacy, and Marshall tapped running back/receiver Bobby Mitchell on the shoulder.

“Bobby Mitchell, sing!”

Mitchell wasn’t just expected to stand and sing there and then—he was expected to do so as the song was played before the exhibition games by Marshall’s own band. He mouthed the words, seething inside. Three-time Pro Bowl offensive guard John Nisby, who endured racist taunts from Pittsburgh Steelers coach Buddy Parker before the 1962 trade that he hoped might put him in a more enlightened place, was expected to do the same.

Marshall should have been booted out of the NFL before he had the chance to do any of that, but that is where we are left.

Ken Behring, Seattle Seahawks

(JEFF HAYNES/AFP via Getty Images)

Behring was a savvy car salesman and lend developer, but the intricacies of doing business in the NFL seemed to elude him. He bought the Seahawks from the Nordstrom family for $80 million in 1988, and it was clear that his goal was to move the team to Los Angeles. The problem with this strategy? Well, Behring failed to apply for relocation with the NFL, he was seemingly unaware that the team was tied to the Kingdome in a lease through 2005, and once he had decided in 1995 to transfer operations to the Rams’ former facilities in Anaheim, California regardless, the league threatened to fine him $500,000 per day until he made Seattle the team’s home base again. Behring made $120 million when he sold the team to Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 1997, but one wonders what made the NFL think he was up to this in the first place.

Hugh Culverhouse, Tampa Bay Buccaneers

(Allen Dean Steele /Allsport)

Culverhouse, a tax lawyer and real estate investor, first tried to gain entrance into the NFL with what he thought was a handshake deal to buy the Los Angeles Rams in 1972 for $17 million, but he was outbid by the aforementioned Bob Irsay. Instead, he was given control of the expansion Tampa Bay Buccaneers after suing the league.

We can’t really blame the Bucs’ 0-26 start on Culverhouse (the roster rules of the time made it nearly impossible for expansion teams to succeed), and he was patient enough with head coach John McKay to let things progress as they did — by the end of the 1979 season, McKay had Culverhouse’s team in the NFC Championship game. However, Culverhouse’s decision to let general manager Ron Wolf walk in 1978 before he was fired was singularly ill-informed, as Wolf is one of the greatest personnel men in pro football history, and he built a lot of the team that rose so quickly.

So, what was the problem? Everything that happened after. Culverhouse’s refusal to pay quarterback Doug Williams anywhere near what he was worth was the most obvious example of his preference for profits over winning. Eventually, Culverhouse’s inability to spend smartly and focus on the things that made good teams good put the Bucs back in the doldrums, and that’s where they stayed well after Culverhouse’s death in 1994. From 1984 (following Williams signing with the USFL) and 1996, when things finally started to turn around, the Buccaneers’ 62 wins were the league’s lowest, as was the team’s .350 winning percentage, and -1,470 point differential.

The Ford Family, Detroit Lions

(Syndication: Detroit Free Press)

William Clay Ford Sr., the grandson of Henry Ford, became a minority owner in the Detroit Lions franchise in 1961, and took over the team in a power struggle in 1963. This was a team that won three NFL championships in the 1950s, and they’ve never gotten past the conference championship (once, in the 1991 season) since. The Lions have cycled through players and coaches at a breakneck pace, but their winning percentage of .418 is the lowest among all teams in existence since 1963, as are their 3226 wins and -1,413 point differential. Amazingly, since Ford took over and through the Ford family stewardship, the Lions have just 12 playoff seasons — in 59 years.

Mike Brown, Cincinnati Bengals

(Syndication: The Enquirer)

When Mike Brown’s father Paul was in charge of the Bengals from the team’s inception in 1968 through his death in August, 1991, the team had the 11th-best winning percentage (.504), the 11th-most wins (171), and the ninth-best point differential (+458). When Mike Brown took over… well, let’s just say that things devolved for a long period of time. From 1991 through 2000, the Bengals had the worst winning percentage (.294), the fourth-fewest number of wins (47), and the league’s worst point differential (-1,131). The younger Brown famously skimped on the scouting the department to a comical degree, and that’s why Cincinnati’s drafts in the 1990s were a big box of yikes. Things got better through the years the decision was made to let head coach Marvin Lewis and director of player personnel Duke Tobin take over personnel matters, but the first decade in which the younger Brown was in charge makes him an easy pick for this list.

Bill Bidwill, St. Louis/Phoenix/Arizona Cardinals

(Herb Weitman-USA TODAY Sports)

Bidwill, whose father Charles bought the Chicago Cardinals franchise in 1933, became the team’s sole owner in 1972. He had been co-owner with his brother Charles in the 10 years before that, and had operational control of the team through his death in 2019, through he had ceded the day-to-day to his son Michael, who currently owns the franchise. During Bidwill’s 61 years as at least part-owner, the Cardinals had just 17 winning seasons and made the playoffs in just eight of those seasons. That four of those playoff seasons came in 2008, 2009, 2014, and 2015 tells you about when Bidwill was less involved.

Bidwill was notorious for running his team on the cheap, as the Cardinals frequently had among the league’s lowest payrolls. His worst move came in 1978, when he refused to let head coach Don Coryell have his way in personnel matters after Coryell’s offensive philosophies had put the Cardinals in the playoffs in two of his five seasons. It was only after Bidwill started letting the players who wanted to be paid walk out the door that things went south.

It came to a head when Coryell stood Bidwill up when the two men were to have a meeting about the coach’s future — Coryell was on a plane to Los Angeles to inquire about the Rams’ open head coach position. Bidwill responded by refusing to let Coryell out of the last three years of his contract, blocking potential positions in Los Angeles and San Diego, and eventually locking him out of his own office.

“Don saw the handwriting on the wall, that nothing good was going to come of staying in St. Louis,” quarterback Jim Hart said years later. “We were very upset that he left. We knew Don was going to be successful wherever he coached, and we wanted to be a part of it. His tenure with the Cardinals coincided with my best years, so to say I was sorry to see him go was an understatement.”

Bidwill finally and mercifully fired Coryell in February of that year, replacing him with Bud Wilkinson and saying, “I’d be inclined to seek out an offensive-oriented coach. I like offense.”

Well, he already had that.