All Tarik Cohen ever needed was a chance

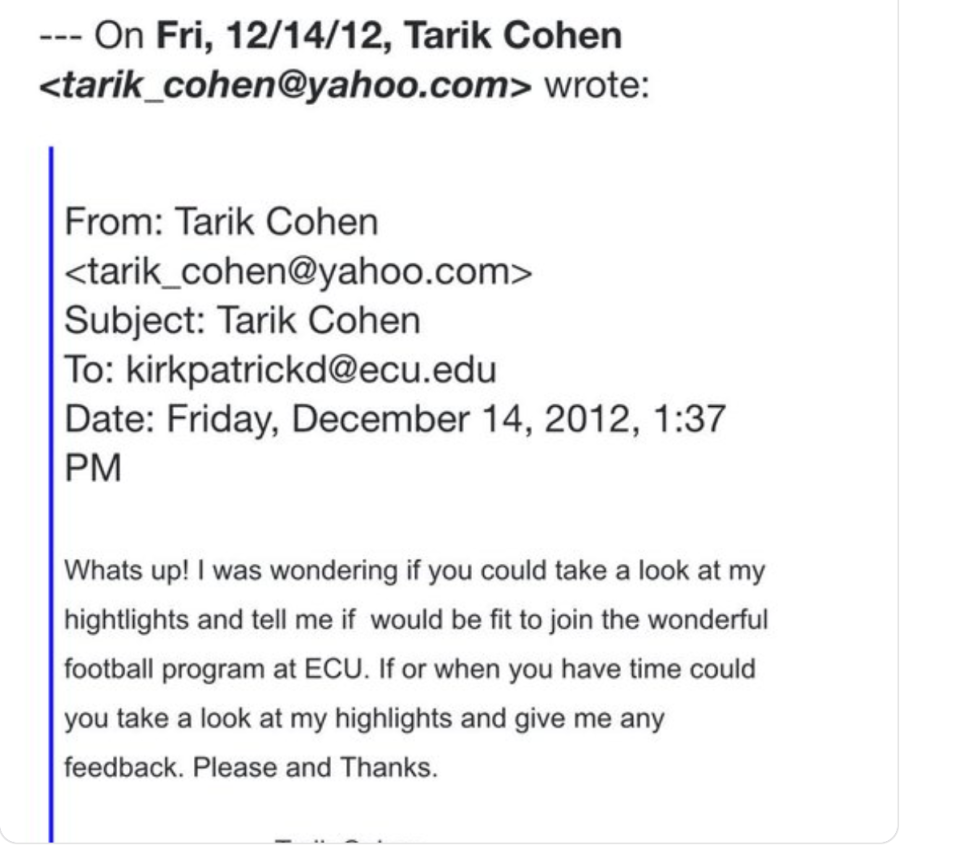

CHICAGO — Before Tarik Cohen became the Human Joystick — before the Chicago Bears‘ do-everything back was bamboozling All-Pro safeties, landing back-flip catches, rewriting record books, or arousing Soldier Field – he was sitting at a computer in his fourth-period class at Bunn High School, dangerously close to his teacher’s desk, composing emails. Clandestine emails.

“What’s up!” he’d begin after slapping his name in the subject line, operating with caution for fear of the teacher’s watchful eye. He’d conclude with a link to a highlight reel that would hypnotize the uninitiated. In between, a plea, to any college coach that would listen: Give me a chance.

There was an unspoken desperation about the exercise. But this, by the winter of senior year, is what Cohen’s recruitment had come to. He had played his last down of high school football. He’d captivated a rural North Carolina town of 344, and compiled his exploits into a motion picture to dangle in front of college talent evaluators. All he needed was one bite.

Yet recruiters came and went. They saw the breakaway speed and absurd production. They looked right past it, right over Cohen’s head. And they’d invariably leave Bunn coach Chris Miller with an all too familiar parting message: “Coach,” they’d say of the 5-foot-6 Cohen, “he’s too small.”

In other words, before the Human Joystick programmed himself with the power to put Pro Bowl linebackers on the seats of their pants, hundreds of collegiate coaches across America were threatening to unplug him. Possibly forever. So contingency plans began to crystalize.

“I had took the ASVAB,” Cohen says, referring to the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test. “I had scored real high. … I was going to go to the Navy.”

Six years later, he sits inside Bears headquarters Halas Hall, speaking just like he moves on Sundays: expressive yet succinct; jumpy and dizzyingly quick; and, most of all, liable to burst with exuberance at any instant. But as he sinks into a sofa, a camouflage-colored jacket preparing him for the early-November cold, the topic of conversation isn’t touchdowns or spin moves or schematic versatility. It isn’t stats or speed or size.

It’s the disadvantages and difficulties that could have preempted all that. It is, in ‘Rik’s words, “perseverance.” It’s the poverty endured; the setbacks withstood; the available excuses shunned.

It isn’t the NFL life Tarik Cohen always dreamed of. It’s the obstacles he leapt over and around to live it.

The fuel

A retelling of Cohen’s journey can begin in many places; after all, he rarely stays still in one for very long. This one begins with sunflower seeds spilling onto a Raleigh, North Carolina, floor. Cohen’s cousin, Cornelius Newell, had bought them. Newell, 11 years Cohen’s elder, has been many things to the now-23-year-old: guardian, role model and trainer among them. On this summer evening, he served as NBA 2K adversary. Against all odds – “He doesn’t even play 2K,” Cohen says – Newell had beaten Tarik. And anger simmered inside Cohen’s teenage body.

After the loss, Cohen eyed the seeds. Because, as he animatedly argues all these years later, “he bought ‘em for me.” Even in defeat, he defiantly thought, “I’m still boutta eat these sunflower seeds.” But Newell had other ideas. Two hands reached for the bag. Pretty soon, neither was chowing down. Instead, they were swinging at each other. The cousins had thrown on boxing gloves to settle arguments before. But this was a legitimate fistfight.

“Our whole family,” Newell later explains, “is sore losers. We hate to lose. But he’s the worst.”

So many elite athletes do. The hatred becomes a work ethic’s catalyst. Cohen, in many ways, is no different. As a child, the rage supplied a temper. After a devastating Madden loss, he hurled his controller at the TV. A separate fit broke his PlayStation. (Cohen, as you’ve probably gathered, was and still is a gaming fiend.)

As the hatred of losing aged, though, it began to stoke an obsession. An obsession with self-improvement. After one set of back-to-back Madden losses to Newell, Cohen begged for a Game 3. Newell refused – and takes the story from here: “He stayed up aaaaaall night practicing, and woke me up in the morning to play again.” The result? “Oh, he beat the hell out of me. He beat me bad.”

Eventually, the competitiveness fused with a love of football and drove ridiculous summer workouts. Newell would devise them: Miles on the treadmill, laps in the pool, pushups, situps, squats. Cohen, more often than not, would complete them. Newell would occasionally float a pair of Jordans or another object of Cohen’s desire as incentive.

But in high school, a new genre of defeat had become incentive enough. Coaches began telling Cohen he wasn’t good enough. Not good enough for varsity as a freshman or sophomore. Not good enough or big enough to succeed at the next level. Cohen interpreted the lack of opportunity as: “I think you’re going to lose.”

And as he says now, “It immediately became fuel” – fuel transcribed in a Twitter bio that begins: “OVERlooked…..UNDERrated.”

Skeptical football minds, though, weren’t the only sources inflaming Cohen’s hunger.

The hardship

Another retelling of Cohen’s journey might unravel chronologically, beginning with a childhood on the move, in search of stability. With uncertainty, stopgaps, and constant upheaval. “We moved so many times when I was in elementary school,” he remembers.

But Cohen isn’t especially fond of talking about all that. Never has been. Never lets it cloud his life. So when I first hint at the family’s struggles, in search of the perseverance that propelled him from backwoods obscurity to this sunlit room lined with Hall of Fame artifacts, he doesn’t take me all the way back. Instead, his mind wanders to eighth grade.

Football, by then, had become a passion. But this particular autumn, several inhibitive factors conspired to make it a void. Cohen didn’t have a ride to and from practice. His mother didn’t have a vehicle. Re-zoned districts left him too far away from school. So rather than strap on an oversized helmet and shoulder pads after his final class of the day, he’d flow right into homework. Or PlayStation. Occasionally tackle football with friends at the park. But mainly “Madden and school,” he says. Football, for the time being, had been stripped away.

The four-letter Q word, though, never infiltrated his mind. Perhaps because adversity, throughout his youth, had been par for the course. Cohen’s father was never a presence in his life. His mother, Tilwanda Newell, toiled tirelessly to support Tarik and his three brothers; to pay for football equipment; to maintain basic necessities.

Sometimes that meant entire weekends away at work, leaving the boys to fix Hamburger Helper, hot dogs and cereal for themselves. Sometimes it meant co-opting the stove as a heater for the whole home. In sixth grade, for Tarik, it meant one pair of jeans. From Walmart. He’d wear them to school three out of five days per week.

But the everyday tribulations, whenever they arose, never seeped onto gridirons. The eighth-grade emptiness merely ramped up ninth-grade anticipation. With coaches and upperclassmen pitching in with rides, Cohen returned to football. By 11th grade, he was a varsity star. In 12th, when Tilwanda moved to Raleigh, Tarik stayed with an aunt, and at Bunn. A scholarship had thus far been elusive. But with one more standout season, Cohen reasoned, he could sustain his dream.

The offer

“Can I tell his family?”

That was Chris Miller’s first question for a college assistant when he heard the news. Midway through Cohen’s senior season, the diminutive playmaker was still without an offer. And without an offer, college would have to wait. The Navy beckoned. But Miller, Cohen’s high school coach, caught wind that a then-FCS school was readying one. He knew, he says, because the recruiter had told him so: Absolutely he could tell the family.

So he did. Excitement built. The following week, a coordinator arrived for the follow-up visit. And the happy ending to Cohen’s scholarship-less ordeal was minutes away.

Or so Cohen thought. He doesn’t quite recall a concrete promise. But he was “under the impression … Yeah, they ‘bout to offer me.”

When the meeting commenced, though, the vibe was “funky,” according to Miller. It concluded with a, “Thanks a lot, we’ll be in touch.” Miller sniffed trouble, and asked for a private word. Minutes later, he was seething. “They kind of rescinded the offer,” he says now. “I went off.”

“Then I had to tell [Tarik],” he continues. “And that’s a crusher, man. Because you have the dream. You didn’t think it was necessarily going to happen. Then it’s there. And then it’s snatched. He could have easily just folded up.”

The opportunity

The two-hour drive through the heart of North Carolina, from Greensboro to Bunn, isn’t the most eventful of excursions. The odd southern fast-food staple interrupts otherwise unremitting greenery. But Rod Broadway, at the time North Carolina A&T’s head football coach, is grateful he made it.

Trei Oliver, a then-A&T assistant, had fallen in love with an undersized running back from the tiny town, and had been imploring Broadway to trek east to see for himself. Broadway’s initial response had echoed dozens of others: Tarik Cohen was too short.

Nobody ever told him so to his face. And size hadn’t prevented him from gashing a defense for 262 yards in a state playoff game. But he was aware. Aware that he just needed one believer. But aware he might not have any.

Until Broadway hopped on the road and saw past the physical traits. Rather than being turned off by Cohen’s size, he was turned on by his “bubbly” personality. Less than a year later, Cohen was slipping in between engaged offensive and defensive linemen at Aggie practice, as if ducking underneath a human arch, forcing coaches to rewind film dozens of times in astonishment. Four years later, he’d toppled the MEAC’s all-time rushing record, and scored more touchdowns than any other player in school history.

These days, he remains fiercely loyal. To the family that supported him, of course. And to his new brothers, his Bears teammates – “watch how you talkin bout my QB boy,” he tweets at Mitchell Trubisky doubters. But his attachment to his school is undying. He rocks A&T sweats; gives back to Greensboro kids; and gloats about rivalry-game victories. And on a Sunday night in November, gives Minnesota Viking defenders the sauce in prime time. But he knows he wouldn’t be here without the one institution that gave him a chance.

The moral

Nowadays, no retelling of Cohen’s journey remains complete for very long. Because nowadays, the Tarik Cohen story adds chapters weekly. It’s the boundless energy. The mazy scampers. The video game-like shiftiness that earned him his nickname.

It’s the type of play that became a regular occurrence back at Bunn, when hundreds bore witness rather than millions. The attention-snaring one-handed grabs. The soul-stealing jukes. The scoop-and-scuttles that rendered squib kicks futile.

Cohen poses a similar all-purpose threat today. He lines up in the backfield and the slot; darts in motion or stays split out wide. He is, to Bears offensive coordinator Mark Helfrich, a “fun toy.” And “there’s more there,” says Helfrich, who smiles dreamily at the thought.

But the 70-yard catch-and-runs, the impossible cuts that infuse frigid Chicago nights with Carolina heat … they’re merely a sliver of who Cohen is. Head coach Matt Nagy hails his “infectious” enthusiasm. Others claim Cohen “never has a bad day.” The energy, according to locker room neighbor Prince Amukamara, isn’t quite bottomless. That is, “unless there’s music playing,” Amukamara says. Then Cohen comes alive.

Just another Sunday Funday at #ClubDub. ¯_(ツ)_/¯ pic.twitter.com/neOxPHqkSK

— Chicago Bears (@ChicagoBears) November 12, 2018

But would Tarik Cohen be Tarik Cohen without all the obstacles? Without the parentless weekends, or the eighth-grade football deprivation? Without his mother’s brief homelessness while he was in college, for which his best antidote was to “hurry up and get to the NFL?”

As if to answer, he heads across town on an in-season off day, to 103rd and South Elizabeth Street, down to Julian High School on Chicago’s South Side. He scans a room full of students, and sees at-risk kids, some from single-parent households, wrestling with hardships. He looks around, and in one sense, sees himself.

He’s reticent to talk about his challenging upbringing publicly, in part because he knows millions of Americans face worse. But here, he’s “equal.” He has come to listen to the teens, to “give them somebody in my position to hear them out.” Somebody who can relate. Somebody who is walking, flourishing proof that perseverance paves a path to rewards.

He now relegates most of his athletic perseverance to back pages. Though he still retweets dismissive scouting reports, and brandishes ignored emails as receipts, most non-believers have become afterthoughts.

But he wants to ensure that kids like 13-year-old Tarik never are. “That’s why I like to share my story and give hope,” he says. Perhaps not hope that others can one day whiz around a football field like the Human Joystick. But hope that endurance pays off.

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.