High-Volume Running Backs

In 1998, Atlanta Falcons running back Jamaal Anderson tore up the league with 1,846 rushing yards and 16 total touchdowns while carrying the ball an NFL-record 410 times. That's nearly 26 attempts per game.

The massive workload appeared to take a toll on Anderson; he played in only two games the following season and averaged just 3.6 YPC during the rest of his NFL career—a career that lasted only 21 more games.

Anderson's case is extreme, but not totally unusual; anecdotally, there seems to be a whole lot of evidence that running backs coming off of high-volume seasons tend to break down in some way the next year. If you ask the average fantasy football player if running backs break down after receiving lots of carries, he's going to respond "of course" and cite Anderson or some other back who garnered lots of touches and was never the same.

I broke down this concept in my first book, but I wanted to come back to it to 1) update the past data and 2) propose some unique thoughts on the subject. So do running backs really suffer after high-volume seasons? Let's take a look.

The Data on Running Backs Breaking Down

Let me save you the suspense: the numbers are overwhelmingly in support of high-volume running backs regressing in the year following a heavy workload. Take a look at how 300-carry running backs from 2003 to 2013—of which there were 75—fared in the following year (Year X+1).

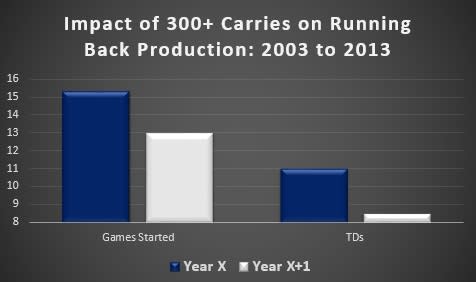

Massive drops—a 15 percent decline in games started and a 23 percent decline in touchdowns. That's pretty startling and of obvious concern for fantasy owners. Running backs coming off of seasons with 300-plus carries have scored exactly 2.5 fewer touchdowns in the following year, on average, which is 15 fantasy points—or about one fantasy point per game from touchdowns alone.

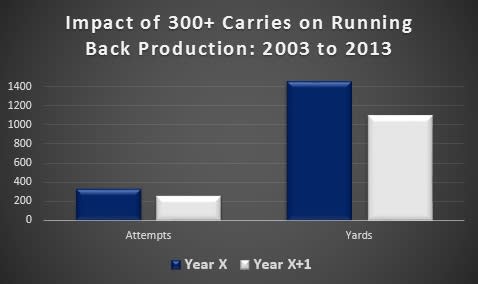

There are other declines in production, too. Take a look at the average number of attempts and rushing yards.

The typical 300-carry running back has seen a massive 22 percent decline in rushing attempts and an even bigger 25 percent drop in rushing yards. If you picked a 300-carry back out of a hat and were asked to predict his rushing yards in Year X+1, you'd probably have a pretty accurate projection if you just sliced his rushing yards by one-quarter.

Well, these numbers are pretty conclusive, right? As Lee Corso likes to say, not so fast my friend…

Editor's Note: For rankings, projections, exclusive columns, mock drafts and tons more, check out our jam-packed online Draft Guide or Draft Guide iOS app, or follow Rotoworld Football on Twitter for the latest news.

Why the Numbers Are Misleading

When we're analyzing any sample of players, we need to ask ourselves if they're representative of the conclusions we draw and if there's any sort of selection bias at work. A selection bias occurs when the individuals we're studying are skewed in some way and not representative of the entire sample.

While there's not an inherent "flaw" analyzing 300-carry running backs to see if they become overworked, there's still a bias toward the type of running backs who reach that threshold of work. Namely, a running back needs certain things to go right for him to see such a heavy workload.

First, he needs to be healthy. Running backs get injured all the time, and I'd argue that no running back is ever likely to start 16 games in a season. That's just the nature of the position. So unusual health is basically a prerequisite for seeing 300 carries.

Second, they need to be efficient. A running back who is averaging 3.2 YPC after 10 games probably won't see a whole lot of carries moving forward. Thus, most high-volume running backs are rushing at a decent level of efficiency.

So what we're really looking at when we examine high-volume running backs is a group that's benefited from better-than-average health and better-than-average efficiency. Both of those things are influenced heavily by randomness, and thus likely to regress in the future. A running back who starts all 16 games is probably going to start fewer games in the following season whether he had a lot of carries or not. Similarly, a running back who rushes for 5.0 YPC is very likely to check in below that number in the next year, again regardless of his workload.

In effect, what we're saying is "running backs who are unusually healthy and probably have higher-than-normal efficiency will have worse health and efficiency the following season." That's pretty obvious though, right?

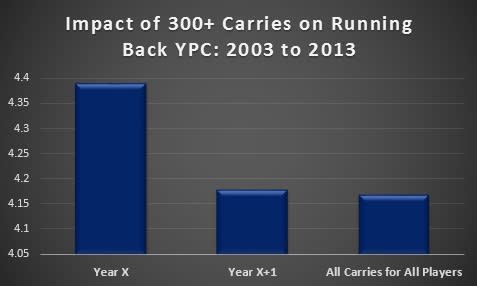

Here's how running back efficiency has tanked after a season with 300-plus carries.

Running backs who have rushed 300 or more times over the past decade have averaged 4.39 YPC during their high-volume season and just 4.18 YPC the next year—a small but meaningful drop of 4.8 percent.

But here's the key: take a look at the rushing efficiency for all players on all carries during that time. At 4.17 YPC, it's actually worse than the 300-carry backs in Year X+1. That suggests that backs aren't falling off of a cliff after seasons with high volume, but rather just regressing naturally. Since the sample of 300-carry backs is naturally skewed to include mainly just those backs with high efficiency and great health, we'd expect a drop in YPC and games played whether they get "overworked" or not.

To lend more credence to that idea, I charted the efficiency of high-volume running backs as the season progresses. If lots of carries really take a toll on a running back, we'd expect decreased efficiency late in the year.

There's no trend here at all. In the final four games of the season, running backs with 300 or more carries have actually been at their best, averaging 4.43 YPC. They don't seem to be breaking down at all. What we're seeing is normal regression toward the mean that's creating the illusion of wear and tear.

The Effect of Age

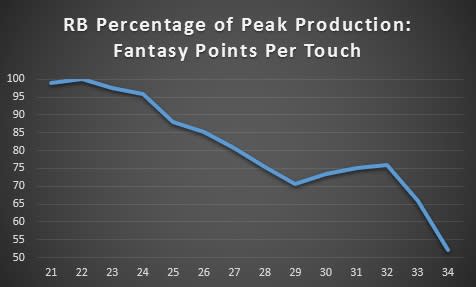

Very quickly, I want to touch on another potential issue—that running backs as a whole are normally going to be less efficient than they were the previous season.

The average age for running backs with 300-plus carries during the time frame I studied was 26.3-years-old. That's right in the midst of a very steep yearly decline for the position as a whole, meaning at least part of the drop in efficiency that we see is due to the aging process.

Summing It Up

Do running backs really get overworked? I don't think so, and if there is an effect, it's likely so small that we can't turn it into actionable information. We do see a steep regression in health, efficiency and bulk stats in running backs who garner lots of carries in a given year, but that's due almost entirely to the nature of that sample of runners—unusually healthy and efficient, and thus in position to post quality bulk stats.

If we analyze all running backs who have abnormal health or very high efficiency in a given season, we see that they also regress in the following year; it likely has very little to do with workload. It's just regression toward the mean.

Further, if you really think about the idea that a few extra carries are going to wear down a running back, it's silly. First, why use 300 carries (or 280, or any other number)? We have to pick a "line in the sand" to study, but it's totally arbitrary. Is a 300-carry back really going to be much worse than a 280-carry running back?

Second, running backs get touches other ways. These studies frequently don't include receptions, but why not? They also don't include practice reps. Teams hit in practice, and some coaches work their players rather hard between games. How can we quantify that effect? What about runners who don't take a lot of big hits (such as a guy like LeSean McCoy) versus players who get hit hard on nearly every run (like Adrian Peterson)?

Sports Injury Predictor—an algorithm that uses past data to predict future injuries—doesn't even include past workload in their model because it has no predictive ability; the biggest predictor of injury is future opportunities, not past touches.

If there's a reason to be scared off by a high-volume back, it would be his age. But that really has nothing to do with the carries and everything to do with running backs naturally breaking down as they get older.

So should you avoid high-volume backs? After all, they do see a steep decline in production in Year X+1. The answer is no, not at all. They're unlikely to repeat their big season, but that's due to that year being an outlier. If you're betting on a running back to remain healthy and record above-average efficiency, there's probably a slightly better chance that a high-volume back will do it than one with moderate "tread on the tires."

In a day and age when there are only a handful of workhorse running backs remaining in the league, there's simply no reason to bypass one because he's coming off a season with some arbitrarily high number of carries; he's likely to regress, but his chances of matching Year X's production in Year X+1 are probably about the same as they were prior to Year X.

Heavily worked running backs will normally see a drop in health and efficiency in the future, but those declines are only correlated with a heavy workload and not caused by it. When it comes to actionable intel, there's not much to be gleaned from a running back's previous workload besides that he's probably in a pretty good spot since he got those opportunities in the first place.