How Deion Sanders' Colorado roster rebuild echoes history from 50 years ago

One of the most intriguing storylines in college football history featured a bold new coach who rode into town and caused a stir after he took over a downtrodden team that had won only one game the previous year.

The same coach then tried to build an instant winner by bringing in more than 65 new scholarship players during his first year – a massive class of newcomers that helped replace the players who quit the team in droves before the season.

But this was not just Deion Sanders, the new head coach of Colorado.

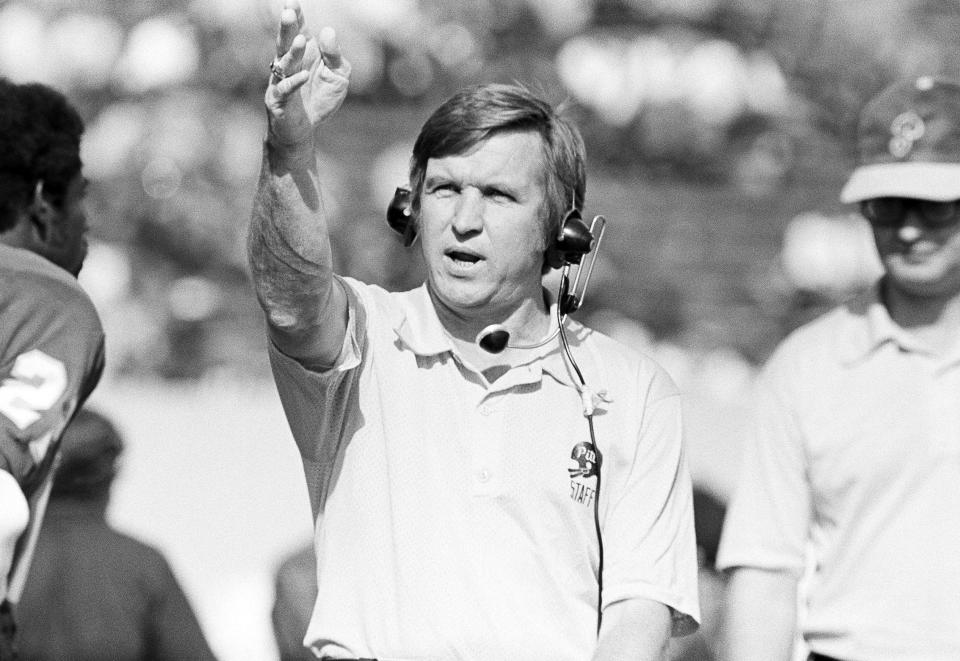

This was also Johnny Majors, the new head coach at Pittsburgh in 1973, 50 years ago this summer.

Their situations are so similar that it fuels wonder about whether Sanders can follow the same trajectory as Majors, who led Pitt back to national prominence in four seasons before departing to coach his alma mater, Tennessee.

A half-century later, Sanders’ drastic roster overhaul at Colorado is unprecedented in its size and dimension.

Yet there may be no closer comparison to it in major college football history than what Majors did at Pitt in 1973. The rules wouldn’t allow it until recently. And the lessons learned from then still echo today.

“In that first year, everyone was hoping for us to win three or four games,” said former NFL head coach Dave Wannstedt, who was an offensive lineman on that ’73 team for Pitt. “We won six and went to a bowl game. So now all of a sudden, everything that Coach Majors and all coaches were preaching and what they were doing, everything made sense. Because we won. That’s going to be the deal with Deion at Colorado.”

How are Sanders and Majors alike?

USA TODAY Sports discussed that year and the lessons from it with three members of that Pittsburgh team: Wannstedt, Pro Football Hall of Famer Tony Dorsett and former college head coach Jackie Sherrill.

“Deion, I think is on the right path to make things happen,” Dorsett said.

Both Pittsburgh in 1i973 and Colorado in 2023 brought in massive recruiting classes with players from across the nation, leading to criticism and suspicion from coaches at other schools. (In Sanders’ case, he recently drew criticism from the current coach of Pittsburgh.)

Each reeled in an uncommonly talented player who could alter the course of a game singlehandedly. Both also benefited from new decisions by their school administrations that eased restrictions for incoming recruits and allowed both to pursue their aggressive rebuilding strategies.

What were the results?

Majors finished 6-5-1 in his first year after inheriting a team that went 1-10 in 1972 and had only one winning season in the previous 12 years. Three years later, he went 12-0 and won the national championship.

Sanders inherited a team that went 1-11 in 2022 and had only two winning seasons in the previous 17. But it’s anybody’s guess how well his team will do this year with what may be the biggest class of newcomers for an established major program since 1973.

That was the last year before the NCAA installed what some informally called the “Majors Rule,” named after the coach, who had taken advantage of a window that was soon to close in major college football. Many schools back then had no limits on how many football scholarships they could give out, unlike now, when each team is limited to 85 overall.

But a year later, the NCAA limited scholarships to 30 per year for new recruits, preventing the signing of such a big class of newcomers until the rules changed again recently.

Colorado “is the biggest since ‘73, no question,” said Sherrill, Majors’ top assistant coach at Pittsburgh before moving on to become head coach at Washington State, Pittsburgh, Texas A&M and Mississippi State.

What was the big deal at Colorado?

What Sanders has done with his first roster is unprecedented because he’s done it mostly through the transfer portal, which did not exist in 1973 and did not become such a big roster-building tool until recently because of rule changes since 2021. Sanders used it to bring in 46 transfers from other four-year colleges, the largest transfer class in the nation. One of them was the No. 1 recruit in the nation in 2022: cornerback and receiver Travis Hunter, who played for Sanders at Jackson State last season.

Along with 17 scholarship freshmen and five junior college transfers, Sanders reeled in 68 new scholarship players for 2023, as of June 30, according to the school.

What was the big deal at Pittsburgh?

By comparison, an NCAA history book published in 2006 noted the extreme case at Pittsburgh in 1973, when “a first-year coach had 83 grants to offer to his recruiting class.” About 70 went to freshmen and the rest went to junior college transfers. One of those new players was the “best football player in the country at that time,” Sherrill said.

That was Dorsett, a freshman running back in 1973 who went on to win the Heisman Trophy in 1976.

“We just started beating the bushes because we didn’t know anybody in that part of the country,” said Sherrill, who had come to Pittsburgh with Majors from Iowa State. “We went south. We signed kids out of Georgia, out of Florida.”

So did Sanders. Both brought in a huge crop of talent. But both still had to clean house to make room for it, to different degrees.

“There was a whole lot of quitting my first year,” Dorsett said with a laugh. “Oh yeah man, it was unbelievable. They had so many guys on scholarship that they didn’t even really know who was on scholarship. John Majors and them came in, and it was cleaning house.”

How did they clean house?

At Pittsburgh, Majors took five buses of players to his first preseason training camp that summer in Johnstown, but only three buses came back after the rest quit under Majors’ tough new physical standards, according to Sherrill and others.

“For a while there, it was a matter of who was going to show up at breakfast,” Wannstedt said of camp that year. Wannstedt said his goal was to “survive” the new competition as a returning player from the previous 1-10 season.

At Colorado, out of a roster limit of 85, only 10 scholarship players from last year’s team remain, including just one who started more than eight games. The other inherited players transferred out or left the team after Sanders told them after his hiring in December that he would try to make them quit. Since April alone, at least 39 entered the transfer portal to leave.

“We’re going to move on from some of the team members, and we’re going to reload and get some kids that we really identify with,” Sanders said after his spring practice finale April 22. “This process is going to be quick.”

What were other key comparisons?

Unlike Sanders, Majors kept a much bigger core of inherited players, including Wannstedt. The 1973 Pitt media guide says the team returned 30 lettermen from 1972, including 16 starters. But the overhaul was still considered drastic and required support from the school's administration to pay for and accept so many new players.

“The biggest resemblance (to Colorado now) is the administration has made a commitment,” Sherrill said. “Pitt opened the door … The transformation was real, and it happened ASAP.”

A roster shake-up like that also never really happened again until 50 years later.

Why not?

The rules changed. Though some think it was in response to Majors’ huge recruiting class that year, that wasn’t the cause. Cost concerns fueled the drive to limit the number of football scholarships per team. So did a new gender equity law in 1972 called Title IX, which called for more funding and scholarships for female college athletes.

The NCAA then set scholarship limits for football teams that went into effect after the 1973 season – an overall team cap that went from 105 and 95 in the 1970s to 85 in the 1990s, the same as it is now, according to the NCAA.

The new rules also limited the number of scholarships that could be awarded to new recruits – 30 per year after Majors’ debut season at Pitt, which later went down to 25. These limits prevented other huge new classes of newcomers until more recent rule changes allowed Sanders to make like Majors 50 years later.

What happened then?

A big new rule change in 2021 allowed undergraduate transfers to change teams without first having to sit out a year at their new school. This created huge demand by transfer players for roster spots on new teams − demand that couldn’t be met under the constraints of the previous limit of only allowing 25 new scholarship players per year.

In response to that demand, last year the NCAA granted a two-year waiver of that limit as long as it didn’t exceed the overall team limit of 85.

“The change is intended to address the impact of the one-time transfer exception in the sport and the extended seasons of competition students received due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic,” the NCAA said in a release last year.

This meant huge new recruiting classes suddenly became possible, if not practical, for the first time since 1973. Enter Sanders, who pounced on it and took advantage of another relatively new rule that made it easier for him to cut players from the team as a new head coach.

This aggressiveness also caused some chirping from critics at other schools, much like Majors had heard in ‘73.

What were the criticisms?

In 1973, after Pittsburgh started the season 6-3-1, the New York Times published a story about the team’s sudden turnaround and its big class of freshmen and junior college transfers.

“Johnny Majors has turned the University of Pittsburgh football team into a winner so quickly that opponents are restless and suspicious,” the article read.

Fifty years later, in May, current Panthers head coach Pat Narduzzi criticized Sanders’ drastic roster overhaul.

“We'll see how it works out but that, to me, looks bad on college football coaches across the country,” Narduzzi told 247Sports.

According to Athlon Sports, an anonymous coach in the Pac-12 Conference also said the situation is “lose-lose” for Colorado with Sanders. “Either he’s gonna be really good really fast and leave for another gig, which, looking at that roster, doesn’t seem possible,” the coach said.

Majors, who died in 2020 at age 85, dismissed the criticism, much like Sanders has.

What's next?

Colorado opens the season Sept. 2 at TCU in Fort Worth, Texas. On Sept. 15, 1973, Majors and Pitt also had a tough season opener − on the road at Georgia.

Pitt missed a 34-yard field goal late in the game and ended up with a 7-7 tie, but the Associated Press reported it as a “surprising” showing by Majors’ team.

“We didn’t beat Georgia in that opener, but on the plane on the way home and the next day in the locker room, we were saying, 'Damn, man, if we make that kick, we’d have beat Georgia,' " Wannstedt said.

A blowout loss in that first game could have had a much different effect.

“You’ve got to win some games you’re supposed to, and the ones you don’t win, the players have to feel like they’re competing now, that they have a chance,” Wannstedt said. “Otherwise, they’re going to say, 'We could have kept the guys we had. Who are these guys? What did we make all these changes for? This didn’t do anything for us.' "

Colorado’s first game seems to have a similar potential dynamic. “That will be like us going to Georgia,” Wannstedt said. “You could draw that parallel.”

The same goes for the overnight change in the team’s outlook after all the roster moves.

“There was more competition because of the numbers, and there was more energy because of the youth in the coaching staff than anything we had been around,” Wannstedt said. “It became contagious.”

Follow reporter Brent Schrotenboer @Schrotenboer. Email: bschrotenb@usatoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Deion Sanders’ roster rebuild at Colorado echoes Johnny Majors in 1973