Coach John McLendon's legacy continues by building pipeline for minorities in athletics administration

As the UCLA men's basketball team was marching through the NCAA tournament this spring, athletic director Martin Jarmond sat down for breakfast with star guard Jaylen Clark.

"It was organic, we just sat there for an hour just talking, talking about life," Jarmond said to USA TODAY Sports. "We weren’t even talking about basketball, just talking about life."

During the conversation, Clark, who declared for the NBA draft after the Bruins were eliminated from the tournament in the Sweet 16, told Jarmond, "You know, I had a high school AD, we had an AD before you got here, I’ve never seen someone look like you being an AD and how you move and how you operate. It’s inspiring."

Why is uplifting minorities in athletics administration important?

Jarmond is UCLA's first Black athletic director. He also was the first to hold the position at Boston College. In 2001, Jarmond was the recipient of the McLendon Minority Postgraduate Scholarship, a program furthering the legacy of John McLendon, the inventor of basketball's "fast break" and a civil rights advocate.

When his basketball career ended due to an injury, Jarmond, who was a senior at University of North Carolina Wilmington, wasn't sure what to do about his future. The scholarship allowed him to attend graduate school at Ohio University to pursue a career in college athletics.

"It matters to our students. Even if they don’t want to be an administrator, even if they don’t want to be a coach," Jarmond said, "to see a leader, someone that is running an organization, it inspires hope and confidence that they can become leaders and do what they want to do."

Adrien Harraway is the senior vice president of the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics and the director of the McLendon Foundation. He spent 13 years at the University of Virginia, climbing the ranks of the athletic department after going to graduate school at Arizona State University as a recipient of the scholarship.

"That just blew my mind that I would be able to get assistance to go to grad school," Harraway said. "... It just propelled my career from there just the network and the financial backing to go get my graduate degree. Because I don’t know how I was going to do it before getting that scholarship."

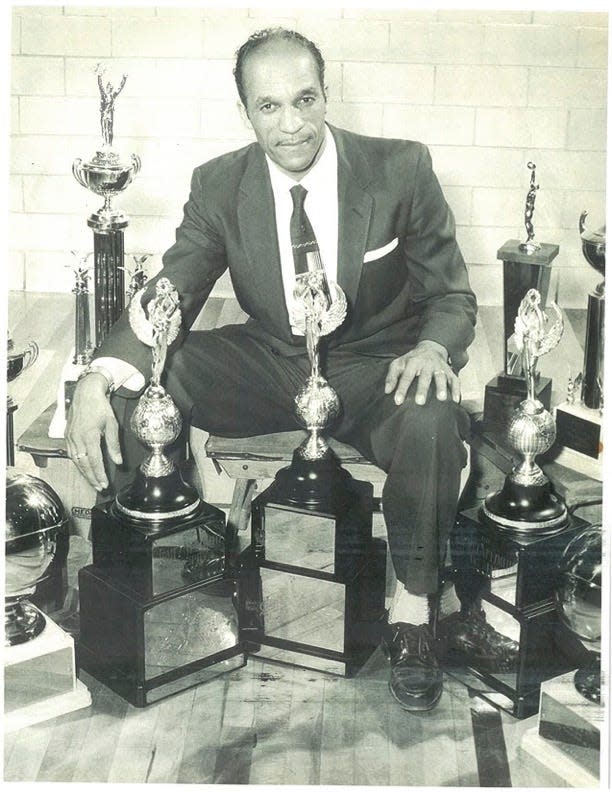

Who was Coach John McLendon?

McLendon was the first person to be inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame twice, as a contributor and then as a coach. He was a student of James Naismith himself at the University of Kansas and was the first Black student to graduate from the physical education program when he received his diploma in 1937. He would later earn a master's degree from the University of Iowa.

While attending Kansas, McLendon led the charge to desegregate the swimming pool. As a coach, he had his team walk to a game when a bus driver refused a player a seat and he also did not commit to participate in an NAIA tournament until he was assured that his team could eat in the same restaurants and sleep in the same hotels as the other teams involved. Black teams weren't allowed to compete in the NCAA tournament and, according to high school basketball coach Dorothy Gaters in the documentary "Soul of the Game," there was a running joke among Black coaches that the association's acronym stood for "No Colored Athletes Allowed."

McLendon won three straight NAIA national championships from 1957-59 with Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State) and in 1966 became the first African American coach at a predominantly white institution when he was hired at Cleveland State.

"When I think it’s hard for me, I think about the battles he had to fight and the path that he had to plow to make it easier for people like me and other coaches and administrators that looked like him to come behind him," Jarmond said. "When you think about that and put it into context just how much he accomplished, what he had to do, it makes it a little easier for me to keep on going. It makes it a little easier for me to see it through because I know that I’m here because of those that came before me and I feel a responsibility to do the same."

A LOOK AT DIVERSITY: The NFL coaches project

McLendon also made his mark in professional basketball, coaching the Cleveland Pipers and becoming to first Black coach in the big leagues in 1962 when the team joined the ABL. He was the first Black coach of an ABA team with the Denver Rockets and also the first Black coach on the U.S. Olympic team.

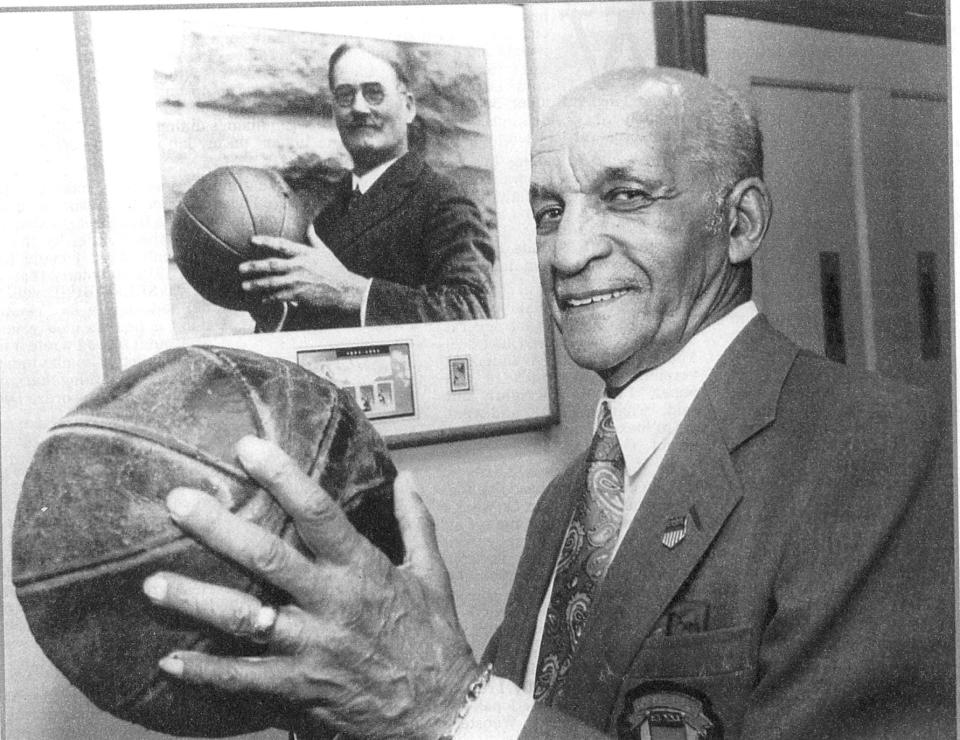

McLendon died in 1999 at the age of 84, but his memory lives on as current players, coaches and administrators acknowledge his contribution to the game. That same year, the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics established the John McLendon Minority Scholarship Foundation.

How did Coach John McLendon help integrate basketball?

A trailblazer for Black coaches, McLendon also won what is now known as "The Secret Game." In 1944, McLendon led his all-Black team from the North Carolina College of Negroes (now North Carolina Central) against the all-white team from Duke University Medical School in a game played in a locked up gym.

"I knew it was against the law," McLendon said in an interview featured in "Soul of the Game," "but it's like any other law that you know is stupid, you just don't pay that much attention to it."

The final score was 88-44. McLendon's team not only won, but dominated.

After the first matchup, the teams split up and played shirts vs. skins in an integrated game in the South during the Jim Crow era.

McLendon was known for his kindness and courage. Harraway points out his relationship with Naismith as exemplary of how McLendon was able to serve as a bridge between races.

"There was something about him that people were drawn to, whether it’s players, faculty that may not look like him," he said.

"That’s what he did being a legendary iconic figure in the world of basketball, but more than that, a gentleman, a leader, a man that gave an incredible amount of service for all people," Harvard men's basketball coach Tommy Amaker said. "It wasn’t just about him doing things for Black people. He wanted to be a person that could help everybody and anybody."

How is the McLendon Foundation carrying on the coach's legacy?

In 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, it was on the heart of Kentucky Wildcats coach John Calipari to make an impact in McLendon's name. He called up Amaker, a longtime friend, to pitch the idea of creating a coach-run program to open doors for people of color in athletics administration. The McLendon Minority Leadership Initiative was born.

"It allowed so many people to have a moment of reflection and a moment of thought and a moment of anger and willingness to want to help and be a better servant," Amaker said of how Floyd's murder served as a catalyst for the program. "And John Calipari I think sat back and started thinking, 'We need to have more Black coaches.' He was really thoughtful in the way, 'Well how do we do that?'...

"He came up with the thought of, 'How do we have more youngsters getting involved in positions and putting them in the pathway and the access of becoming more leaders?'"

The coach-led and -funded program has placed students on more than 100 college campuses from across the country. The scholarship program continues to give out awards to eight students a year and has given away more than $1 million in tuition assistance.

Jarmond is noticing the positive change because of programs like these from The McLendon Foundation.

"I’m talking to younger minority professionals that are calling me for advice and counsel," he said, "and it just seems like they’re more in the pipeline. And that’s what we’ve always talked about is getting younger people, minorities, in the pipeline so that we can have more people to fill spots that come open and grow and develop them in their career."

The McLendon Foundation's logo is a torch because Harraway wants every student impacted by the organization to recognize that they are carrying the light of coach McLendon's work.

"Sports is the ultimate example of life and how you can succeed," Harraway said. "Because you need help and you can’t do it on your own. You need your teammates and you need other people from coaches to help you succeed."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coach John McLendon's legacy carried on by foundation work