Cirqula Logic: ‘Vulnerable’ Athletes Say They Were Played by Social App

Welsh badminton player Jordan Hart recalls the desperate state of mind she was in this past April, when she first came across a new professional athlete influencer app called Cirqula.

Two months prior, Hart’s father, a lorry driver, had fallen headfirst out of his truck, cracking his skull and suffering a brain hemorrhage. Though he ultimately survived the accident, Hart says the injuries prevented him from getting back behind the wheel and, therefore, earning his living. Hart, 27, had relied on her parents’ assistance with travel and tournament expenses that can easily exceed $30,000 a year.

More from Sportico.com

Having been ranked as high as No. 60 internationally, Hart was still trying to crack the elite threshold of players who could actually earn a living playing the sport. Now, she felt she could no longer accept her family’s help in pursuit of that goal.

“I was in quite a vulnerable situation in my personal life,” she said. A little online research led Hart to Cirqula, which presented itself as a saving grace—a social media platform geared at maximizing the branding value of up-and-coming professional athletes.

A couple of months after she began following its Instagram account, Hart received a direct message from Cirqula, soliciting her to join. After providing some information online, she received a “personalized performance offer” guaranteeing £9,000 ($10,162) in Year 1 to be among the platform’s early adopters. What the athletes were expected to do in exchange was vague, beyond helping bring their social media followings onto Cirqula’s platform. The introductory email suggested the athletes would not need to spend more than 30 minutes a week on the platform to earn their keep.

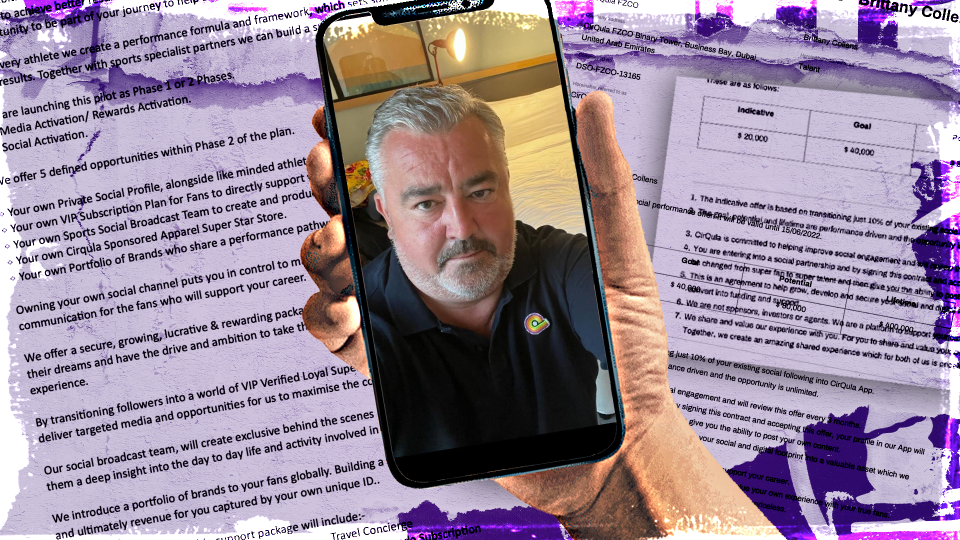

“Now you can afford your dream,” proclaimed the email message that accompanied Hart’s offer. But to join, Hart was first required to pay an upfront onboarding fee of €230 ($228), which was later explained to her as a means of weeding out those who were not truly serious about committing. The company, according to its Scottish founder and CEO Craig Rutherford, didn’t actually need the athletes’ money. It already had serious investors, he assured them.

The official Cirqula contract Hart ultimately signed stipulated minimum earnings of $11,340 a year if she were to convert 10% of her current social media following into Cirqula users, though it was left unclear what she was supposed to base that on. (Hart currently has a little over 14,000 Instagram followers.) Nonetheless, she says she was repeatedly told by the company’s recruiters that she could bank on the guarantee, even if she didn’t reach the conversion goal in the first year. However, six months later, she has received no payments, and her attempts to receive a refund of the €230 upfront fee have been unsuccessful.

Hers, it turns out, is not a unique story.

Over the past month, Sportico has spoken with nearly a dozen athletes and several other sources who claim they and scores like them have experienced similar problems with Cirqula. Wooed to the startup platform with promises of thousands of dollars guaranteed each year and various bonus opportunities, the athletes say they endured one delay after another. First, there were a handful of holdups to the official launch last year. Then, there were several snags leading to the release of Cirqula’s app—a “shit original form of Instagram,” according to Elliot Bradley, a British golfer who was among the early adopters. Then, there were purported payment processing difficulties. Finally, the company told the athletes this September they could either rework their original arrangements (with far less desirable terms) or accept refunds.

And yet, many who pursued the refund option are still waiting for that money to be returned. After Cirqula had ceased responding to their status update requests for over a month, the athletes received an email last week from a consultant working for the company, who suggested that the latest hold-up was on account of the athletes going public about their experiences. In his message, Dominic Hayes, the managing director of British sports marketing firm River Media Partners, raised the specter of Cirqula now suing some of its critics, saying, “there has been some significant public defamation.”

Sportico initially requested an interview with Rutherford on Oct. 25, but he said he was busy traveling that week and offered instead to talk last Tuesday. However, shortly before a scheduled Zoom was to take place, Rutherford sent a message that he was sick with COVID and unable to speak. He subsequently declined to address a long list of written questions, describing them as “embarrassing” and saying he would “put them in the hands of our legal team.” He declined to identify who was representing him.

Target Market

Beyond the specific accusations being leveled against Cirqula, the ordeal opens a window into the precariousness faced by so many pro athletes who live on a financial knife’s edge—racking up credit card debt, depleting their savings and putting other money-making options on hold to pursue their sport at the highest level. With little leverage and major travel expenses, they are often compelled to take seriously any financial offer that comes their way, including those dangled over Instagram messenger.

In this case, several of the athletes said they didn’t think Cirqula’s objective was to simply run off with their entry-free payments. Rather, they believed the company had indulged a not uncommon startup tactic of faking it until you make it—and didn’t want to concede failure.

Cirqula initially targeted only tennis players, but eventually expanded its scope to include golfers and other sports participants. While its target demographic consisted of athletes on a shoestring budget, Cirqula was able to draft at least one high earner: Australian tennis pro Ellen Perez, currently the world’s 18th-ranked women’s doubles player, who has made over $400,000 in prize money this year. Cirqula snagged Perez with a guaranteed minimum of around $9,600 per year. In a phone interview, Perez said that although this amounted to a small fraction of her yearly income, it was effectively tendered as free money. She says she also liked the idea of supporting a company that appeared to be on a noble mission.

“They marketed themselves as wanting to help the athletes who were struggling,” Perez said.

She and other athletes say they are now going public to warn others away. In addition to giving interviews, they provided copies of contracts, offer letters and proof of entry-fee payments, as well as emails, WhatsApp messages and voice memos they received from Rutherford and his two Irish collaborators, tennis promoters Mark Wylam and Noel Walsh. Wylam declined to comment, and Walsh did not respond to repeated messages sent over email and WhatsApp.

Cirqula’s Court-ship

Though Cirqula’s onboarding fees were relatively modest, they were not necessarily affordable. Brittany Collens, a former Division I tennis player at UMass who since made a name for herself as a college athlete advocate, says she had to borrow money from a friend to make the initial payment. Collens was among the first of the early adopters who signed on to the platform in the fall of 2021, for what was supposed to be a three-month pilot program. Her deal came with the understanding that Cirqula would pay her a minimum of $20,000 a year once it officially launched.

The early adopters were told that, in addition to the guaranteed money they received, they would be able to partake in the Cirqula Rewards Program. According to the pilot agreements, Cirqula was already “working” with major international brands like Adidas, New Balance and Reebok. When asked by Sportico, representatives from those companies said they did not have any relationship with Cirqula.

Collens recalled her initial conversation with Walsh and Wylam in September 2021, in which she says Walsh described Cirqula as serving as the athletes’ “fairy godparents.” Acknowledging that their pitch sounded too good to be true, she says Wylam implored her to trust them that it wasn’t.

Well beyond the entry fees, athletes say the financial consequences of their involvement with Cirqula were compounded by the decisions they then made under assumptions that the money was coming.

Advan Mujevic, a 22-year-old tennis player from Sweden, says he quit his retail job soon after accepting an early-adopter deal with Cirqula in October 2021, which promised him at least €26,000 per year.

“I can’t explain in words about how much it impacted (athletes),” said Mujevic, whose young tennis career has been hampered by injuries and setbacks. “It is like you are homeless, and you get a rich guy that buys you a house.”

Mujevic said that when it eventually dawned on him that the payments might never come, he was completely demoralized.

“I don’t know how much I should open up at the moment,” Mujevic said, choking up during a phone call last month. “I am pretty depressed.”

Mujevic first learned about Cirqula when Walsh approached his girlfriend Kseniya Sundin, another Swedish tennis player. With more than a million Instagram followers, Sundin was among Cirqula’s most followed content creators, though she had previously struggled at capitalizing on her social footprint.

She recalled a less-than-fruitful experience working with another European influencer online marketplace, which she felt had priced her rate for sponsored posts too high. Later, when she decided to deal with companies directly, she mostly ended up bartering her endorsements for products or services. In the few instances in which she was offered cash, it was no more than a couple hundred dollars per post.

When Sundin was initially informed about Cirqula’s onboarding fee, she says her instinct was to bail out immediately, but that Mujevic persuaded her to join. In addition to the money, he believed Cirqula would help both of them continue their tournament play.

As with Sundin, several of the athletes Sportico interviewed said that they engaged Cirqula with their eyes wide open, but that their initial skepticism was overcome, in no small part, by the way in which Rutherford, Wylam and Walsh demonstrated a keen understanding and empathy for the unique financial challenges they faced. In retrospect, athletes say, this makes them feel even more victimized by the experience.

In her introductory call with Wylam and Walsh, Hart said she promptly laid her negotiating cards on the table by explaining the situation with her injured father, hoping this disclosure would pull at the heartstrings of any potential hustler. She was left feeling assured by their reactions.

“I remember coming off the phone and going to my mom and saying they asked a lot of questions about dad,” Hart said. “It came across as kind questions, and that is what makes it worse. I came off [the call] thinking, ‘Maybe this isn’t a scam, they seem like legit people.’ You know if you are being scammed, they wouldn’t have taken 45 minutes just to scam me.”

Tiphanie Fiquet, a French tennis player and current graduate transfer at TCU, says she was already leery about Walsh, given a previous experience with him. Two years prior, Fiquet says she entered a tournament in Birmingham, Ala., as part of an upstart American tennis league Walsh was trying to launch. (Walsh’s company, TennisInvestor.com, lists both Cirqula and Wylam’s Talent Pros International as two of its three portfolio companies.)

Fiquet recalled that the event, which had promised a four-figure purse, ended up not having enough participants, and players were relegated to teaching lessons in order to make any money.

However, Fiquet says her coach in France vouched for Wylam, based on positive past experiences. Fiquet reached out to Wylam in the spring and signed a Cirqula contract in early June that guaranteed her $500 a month, after she paid the €230 entry fee. Fiquet says she immediately started posting on Cirqula’s platform and quickly converted more than 10% of her modest Instagram following into Cirqula “super fans.” By the end of July, she wrote to Wylam asking why she had yet to be compensated.

In a follow-up voice message, Wylam explained that he was in the process of assessing the content creators’ production, up to that point, to determine who “deserved to be paid” first. He assured Fiquet that, “because of the work you have done,” she and Collens were on that list. Though he was uncertain when the payments could go out, he implored her to post “a little bit more” and to invite more people to join. Fiquet says that was the last she heard from him.

‘Incredibly Convincing’

Like Fiquet, David Gommez, an American-born tennis strength and conditioning coach based in Bangkok, says his previous dealings with Wylam had convinced him to bring nine athletes and other coaches aboard Cirqula’s platform this summer. Gommez says Wylam’s company, Talent Pros International, was known to have a positive reputation in international tennis coaching circles.

“I decided to trust him at his word, and he emphasized the urgency to sign up with a paid subscription,” Gommez said.

Motivated in part by Cirqula’s referral bonus offer, Gommez says he ended up paying the onboarding fees for three others–a tennis player, a triathlete and an MMA coach—and promised six more athletes who joined Cirqula after his recommendation that he would comp their fees if it didn’t work out for them.

Now that it hasn’t, Gommez says he is personally in the hole for over €2,500 euros. But of greater consequence, he believes, is the reputational hit he has taken.

“My credibility in that regard is lost,” Gommez said. “This is more important to me than money.”

Cirqula’s biggest known financial commitment was the deal it struck with The English Trophy, a first-year event on The Challenge Tour European golfing circuit. According to the tournament’s organizers, Cirqula had agreed to be the inaugural title sponsor at a cost of several hundred thousand pounds. However, last month, a message posted on The English Trophy’s Instagram account announced it had severed ties with Cirqula and was contemplating litigation.

Daryl Evans, a sports marketing consultant whose firm, Rocket Yard Sports, is one of The English Trophy’s co-promoters, said that after Rutherford failed to make good on an initial six-figure installment, the event tried to work with him by allowing a more flexible pay schedule. Instead, Evans said, Rutherford tried to argue that the sponsorship agreement had been nullified because The English Trophy failed to deliver enough of its participants onto Cirqula’s platform. Evans says this was not part of their contract and now believes Rutherford never had the money to pay in the first place. In light of his experience, Evans says the athletes shouldn’t feel bad about falling for Rutherford’s pitch.

“He was incredibly convincing,” Evans said. “I come from South Africa; I don’t trust anybody anyway.”

Paper Trail

At the same time Rutherford was presenting himself as the financial lifeline for striving athletes, he was apparently, unbeknownst to them, leaving a trail of unpaid debts. Gayle, a former girlfriend of Rutherford’s, who asked that her last name not be used, provided photos showing numerous notices and court filings against Rutherford in Scotland, suggesting he potentially owed tens of thousands of pounds in back payments.

The various documents—which Gayle said Rutherford left behind at her home after their relationship ended—included an eviction letter for an apartment he leased in Edinburgh, along with numerous other collection notices for past due bills. As with the athletes, Rutherford attempted to convince the Scottish courts that he was standing on the precipice of a moneymaker.

“Whilst this [funding] has not yet arrived, we are now in the pilot phase of launching this business,” he wrote to a court in August 2021, when petitioning for additional time to address one of his late payments. “I am happy to provide assurances of infusion to support this.”

According to Gayle, who says she and Rutherford dated from April 2021 to April 2022, the revelation of his delinquencies came as a surprise given how he lavished her over the course of their relationship.

“When we were going out for dinner, we were having champagne and lobster,” Gayle said. “It wasn’t like we were going out for burgers and beers. I stupidly never asked a lot of questions.”

When they first began dating, Gayle said she was under the impression Rutherford’s company was already up and running. He spoke of Cirqula’s success in finding partners, from streaming platforms to crypto companies, and high levels of interest from incredibly wealthy firms in coming on board. “The whole time he was telling me, ‘This time next year, I’m going to be a millionaire.’”

Rutherford’s LinkedIn profile shows that his pre-Cirqula résumé included working as a commercial director for an English CBD company and forming a handful of short-lived marketing firms, including a grassroots, sports-focused one called “Wear the Shirt.”

Gayle claims their relationship ended with Rutherford owing her money. Last fall, she said, Rutherford returned home from Ireland carrying “literal pockets full of” euros, which he said he was unable to deposit in the bank. Gayle said she agreed to trade him an equivalent amount in pounds, providing Sportico a screengrab of her online bank account showing a transaction of £2,500 to Rutherford. She says she kept the stash of euros in her home until Rutherford took them with him the following month on a trip to Spain, never reimbursing her afterward.

Waiting Game

Some of Cirqula’s earliest adopters, including Collens, were told they first needed to create an online profile through Wylam’s Talent Pros International, for a cost of €70. That was in addition to the onboarding fee of around €230 to become a Cirqula “content creator.”

“You’re likely to get so much access to more funds and more money and also more sponsorship opportunities that it’s crazy for you to have to turn it down based on [the onboarding fee],” Wylam told Collens in a voice message in late October 2021, after she expressed hesitation over having to pay the Cirqula fee. She says this wasn’t disclosed in their initial conversations.

Pilot agreements, which also made reference to an additional 3% management fee, were distributed last year to an initial group of early adopters while Cirqula’s app was under development. The athletes who spoke to Sportico estimated that there were ultimately between 100 to 300 “content creators” who joined the app, with many more waiting in the wings for proof of concept. In addition to posting content and trying to convince their followers to become Cirqula “super fans,” Cirqula offered financial incentives for the talent to bring others into the fold.

The platform’s official launch date, which was first supposed to be around Thanksgiving 2021, was pushed back month after month. Over the course of the delays, Cirqula’s organizers offered various explanations for why even the initial months’ payments had yet to be disbursed, insisting it had nothing to do with their core business model.

Throughout the recruitment phase, sources said, Cirqula repeatedly made it seem as if everything was going better than expected. In a series of webinars he hosted at the start of this year, Rutherford described the possibility of Cirqula exploding into a “multibillion-pound business.” Though he was sparse on specifics, he repeatedly alluded to major investors he had already lined up.

At the same time, Rutherford began slipping new variables into the mix, though he said they would only benefit the early adopters. For example, during a Jan. 19 call over Google Meet, Rutherford said that Cirqula had decided it would review the payment structure for each athlete every three months, based on 40 key performance indicators. However, the initial guarantees would remain intact for at least 12 months.

“You guys are the first ones and will always be dear to our hearts,” Rutherford said.

In a video conference a month later, on Feb. 24, Rutherford reiterated that, behind the scenes, things were going even better than he hoped. If anything, Cirqula was almost getting too big, too quickly.

“A lot of what I have set out to create with this business has really shaped in the last few weeks and really brought together a much stronger proposition than we originally set out to achieve,” he said.

So why hadn’t anyone gotten paid? Rutherford chalked it up to a logistical matter.

“One of the issues we faced in our pilot [program] is we can’t send transactions or payments to thousands of athletes,” he said. “Banks will close you down.”

So the athletes were instructed to open up new accounts with a bank in the United Arab Emirates, where Cirqula was registered as a business. Later, they were told that their disbursements would come through a fiat/crypto wallet app. In May, Rutherford explained that the company had finally secured a deal with Visa to become its payment facilitator. “This has been the major hold up,” he wrote to Collens in a WhatsApp message, “not money.” He added that there were “10,000 athletes coming on board alongside major sponsors and major investment.”

At the same, Rutherford was trying to fend off the pleadings of his ex-girlfriend to repay the £2500 Gayle says she loaned him.

“I’m operating off a credit card and desperately waiting for this [Cirqula] account to open,” he wrote her on May 22, claiming to have only £150 in his bank account at that point.

Two days later, Cirqula sent out a “Welcome Message” to the athletes, which began, “All good things come to those who wait…we will now reward your patience by supporting your future career.”

Though it had still yet to pay them any money, it now purported to offer a wide-ranging “Cirqula Support Package,” which included personalized pro coaching, travel insurance and travel concierge service.

‘False Promises’

In June, Cirqula sent out new contracts for the athletes to sign, including those early adopters who had previously inked pilot agreements. The official contracts shielded Cirqula from liability for delays or failure to hold up its end of the agreement to the extent that such missteps were “caused by an event beyond its reasonable control.” The documents also set forth that any disputes between the company and its contractors would be adjudicated according to UAE laws.

One crucial distinction within the new contracts were “indicative” minimum payments contingent on the athlete converting 10% of their social media followers to Cirqula users. There was no timeline given for when this needed to be accomplished, nor specifications on how the athletes should calculate their current followings.

Perez and others sought clarification from Wylam, who had previously promised that she would receive her first payment by the end of April.

Wylam sought to allay her concerns in a voice message, explaining that since Perez was originally part of the Cirqula pilot program, her “indicative” amount was still guaranteed, regardless of her conversion rate.

“The reason that (says) ‘indicative’ and not guaranteed is because we are preparing this contract for everybody and only our first early adopters get access to the guaranteed amount,” Wylam said. “So, we are sending the same contract to everybody but it is important that you know that the ‘indicative’ offer is your guaranteed payment.”

Rutherford relayed the same assurances to Collens, telling her in a text message that early adopters “remain guaranteed,” despite the contractual changes suggesting otherwise. “We are very confident this will be much more lucrative than our initial projections,” he wrote.

Other athletes told Sportico that the Cirqula organizers repeatedly downplayed the idea that their baseline pay was contingent on reaching the 10% conversion.

As Cirqula’s terms were shifting internally, Rutherford continued to assure Gayle that his personal financial windfall was imminent. In a message sent June 22, two months after their breakup, Rutherford wrote that he had just signed a contract for “$300K a month,” due to kick in immediately. He said he hoped to pay her that week, but admitted he was “a bit skint to say the least, so [I] have to wait for this to drop.”

June turned into July, then August, and still no one had received any money.

Like many of the other athletes, Elliot Bradley, who had joined Cirqula with the expectation of earning £700 per month, was losing his patience. He was told in March that if he paid the entry fee within a certain timeframe, he would be eligible to receive his first check in April.

Banking on that, Bradley had decided to dramatically scale back on his work as a golf instructor, his main source of income. He was chewing through his savings, £2,000 of which he set aside to attend the European Tour Qualifying School, which was set to open in this year for the first time since the pandemic. Bradley says that, at one point, when he relayed his financial concerns to Wylam, he was encouraged to put the Q School fees on a credit card, under the expectation the Cirqula money would arrive soon afterwards to pay it off.

“That was the point that really frustrated me,” Bradley said. “Because now he’s not just trying to cheat people out of a few hundred dollars, he’s encouraging people to make really reckless life and career choices on false promises. Ethically, that’s a whole different thing.”

Group Chat

On Aug. 9, Cirqula’s Instagram posted a photo of Rutherford at a Hilton hotel in Dubai, posing with retired British boxer Amir Khan. Tagging Khan, Bradley commented on the post with a message castigating Rutherford for “conning hundreds of young sportspeople out of money with empty promises of support.” The Cirqula account deleted Bradley’s comment and replied in the thread intimating potential legal action, which marked a shift in the company’s tone with its partners.

Increasingly, athletes were being told by Wylam and Rutherford, in messages and phone calls, that they weren’t pulling enough of their weight. When Petra Januskova, a Canadian tennis player, pressed Wylam about her money over WhatsApp, he suggested she was out of line.

“Unbelievable,” he wrote. “Do you get money before you play tournaments? DO you get paid for working at burger [sic] King before you have done any work?”

In late August, Perez met Wylam face-to-face, for the first time, at tennis’ U.S. Open, where she would eventually reach the semifinals in women’s doubles. In a conversation she described as having an “awkward vibe,” Perez says Wylam blamed the athletes not getting paid on The English Trophy failing to recruit thousands of golfers to the app.

Two days after she met with Wylam, Perez received an Instagram message from Collens, who had begun reaching out to other tennis players on Cirqula’s app to compare notes.

For better or worse, Collens had some formative experience as an unpaid athlete under siege. Two years earlier, the NCAA put UMass women’s tennis on probation and vacated many of its previous wins after finding that in 2015, Collens and a teammate had improperly received $504 dollars in extra scholarship money from the school. For what amounted to a “clerical error,” Collens later wrote in an April 2021 essay for The Players Tribune, “the NCAA wiped my career—and my teammate’s—from the record books.”

“The biggest thing I learned from the NCAA is to follow the money,” Collens told Sportico. “And (Cirqula) is another situation where athletes are getting screwed over by a money situation where somebody wants to take advantage.”

Over the course of a few days, Collens’ Instagram reach-outs soon turned into a group chat of several dozen Cirqula content creators. Several said they were relieved to find out that they weren’t the only ones in this position. Collens wrote up a demand letter she planned to send to Rutherford, asking for the reinstatements of their original terms or refunds of their entry fees. Though she never sent it, a draft was leaked to the Cirqula boss.

“We are really hurt,” Rutherford texted Collens on Sept. 3. “We are trying to help atheletes [sic] and events and this witch hunt is unbelievable.” In a series of back-and-forth messages, Rutherford alleged that Collens’ “actions” had imperiled a £750,000 deal between Cirqula and a British professional tennis circuit called the UK Pro League. “Our lawyers will be in touch,” he added.

A week later, the athletes received an email from Hayes, a former WWE executive whose River Media Partners runs the UK Pro League and had been recently hired by Cirqula. Hayes offered the early adopters two choices: They could accept revised agreements, which provided far less money in exchange for much greater commitments, or they could terminate the relationships and receive their entry fee back.

“Cirqula are sorry that these changes have been a cause of stress for some,” Hayes wrote, “but sincerely hope that you will take this opportunity for a fresh start to build what they believe is a revolutionary platform that enables talent to realise the value of their social following.”

Despite Hayes’ proposal, none of the early adopters interviewed by Sportico who requested refunds have received anything, nor were they aware of any other Cirqula athletes being reimbursed.

Hayes declined to directly address whether his company was ever discussing a six-figure partnership with Rutherford’s, but told Sportico in an email last week that he continues to want to “work with Cirqula on a long-term basis.”

When asked about the message he sent last week on Cirqula’s behalf, threatening a potential defamation suit against some athletes, Hayes said: “Cirqula need to be certain of their legal position as it relates to some of the public comment that has been made before moving forward on this. This is understandable and it is what has held up the process over the last few weeks. We are trying to ensure that players understand that this is a work in progress and to maintain communication with them rather than them feeling that they aren’t being heard.”

Risky Business

Collens says she is currently in the process of “trying to figure out my finances,” now that she has resolved that a $1,600 monthly check from Cirqula is never coming.

“I don’t want to say I banked on that, but I did make poor decisions to go on more expensive [tennis] trips,” she said, lamenting, in particular, the trek she made in August to Europe, which prematurely ended after 11 days when she got sick.

As of a few weeks ago, Collens was prepared to retire from her sport, but after speaking to her coaches, and in light of some good tennis she’s been playing of late, she decided to postpone that decision. For now, the only thing she is sure of is she won’t be traveling through the remainder of the year.

“I can’t afford to go to these one-off tournaments,” Collens said. “It is not conducive for anybody who doesn’t have a lot of money.”

Several of the athletes said that their experience with Cirqula had taught them to raise their bar of scrutiny for any future business opportunities they are pitched, especially if it requires them to be a first mover.

On the other hand, there is the risk of not taking risks.

Jordan Hart, for instance, plans to continue pursuing professional badminton’s pinnacle, despite her mounting financial challenges. To supplement her income, she has started coaching more and recently began giving paid motivational speeches at schools. She got this gig through a company called Sports for Champions UK, which she started following on Instagram over the summer. As with Cirqula, the company sent her a direct message, asking if she would be interested in talking about an opportunity.

Given recent experiences, she admits to being hesitant. But she accepted the overture, and the gig has gone well so far. Whatever is to come, Hart sees no other option than to proceed optimistically.

“I am in a situation where I want to do my sport, but I need help,” she said. “So, I have to be the one who is open for help. I am at the mercy of everyone. I have to take everything at face value.”

Best of Sportico.com