Ann Arbor is losing a piece of history. Here's what Angelo's means to me, and so many others.

I learned to write while working a grill.

No, really.

Of all the mentors and freelance editors I had, of all the high school English teachers and professors, nothing taught me more than standing over a sizzling flattop, tickets flying through the window, trying to organize and time up short stacks and omelets, French toast and hash browns, eggs and sausage patties and grilled cheeses.

Newspaper deadline pressure is a thing, sure. But making certain an eight-top gets its food at the same time while the waitstaff peers through the window?

That can make your knees buckle.

Steve Vangelatos made sure mine rarely did. I don’t think I’ve ever told him what his restaurant meant to my journalism career, or to me in general. So, I'm telling him now:

Everything.

I’m not at the Free Press without Angelo’s. Thousands of others could say the same and, in fact, hundreds have said the same to Vangelatos since news broke last week that he was selling his venerable breakfast and lunch spot to the University of Michigan.

They grew up with his food. Took finals with bellies full of corned beef hash and eggs. Made rounds as medical residents dreaming of his open-faced turkey sandwiches and deep-fried French toast.

Learning how to stand over a bustling grill with a line out the door offered confidence. So, too, did surviving — even occasionally thriving — inside one of the busiest restaurants in Ann Arbor.

To call it a restaurant, though, is to undersell what it’s meant to Ann Arbor and beyond. It’s an institution, first and foremost. A meeting place for college students and townies, local politicians and football coaches (Lloyd Carr was known to sit at the counter), for plumbers and mechanics and sales folks and medical students, of whom Vangelatos fed by the thousands over the years.

He has heard from hundreds of them in the last week, and even for those that knew it was coming, it was a shock.

“So many numbers I don’t recognize,” he said. “I have to respond: ‘Who is this?' I feel bad.”

He shouldn’t. What matters is that they know him and Jack Juback, his brother-in-law who partnered with him in the early 90s and is also a face of the corner of Glen and Catherine, hard by U-M's medical school.

“Jack’s a people person,” Vangelatos joked. “I’m not.”

That’s not entirely true. He just likes people from a little more distance, likes to head out from his bread mixer and ovens and survey the crowd, soak in the noise of silver on plates, especially plates that are about emptied.

He has also loved the stories the past week, about how couples found each other at his place or customers met future employers or grieved the loss of a loved one over pancakes and a simple cup of coffee.

Stories about what his place meant to them. The recollections have stunned him, truthfully, because even the owner of an “institution” can have moments of doubt, questioning why it became an institution in the first place.

“We’ve talked about it often,” Juback said. “The food? The atmosphere? The exposed brick? The history? The vibe?”

How about all of it? Restaurants are hard to break down into parts that way. Sometimes alchemy just happens, like when making a movie, or writing a story.

Vangelatos took over from his father in the early 1980s, doubled the seating and size of the kitchen, turned a neighboring house into a café and the to-go arm of the restaurant (run by Juback) in the early 1990s, all the while getting up at 4:30 in the morning for decades to make bread.

Not just any bread. But raisin bread, the kind of bread that inspired lines around the corner for generations (his father, Angelo Vangelatos, opened the place in 1956).

I started in 1988, not long before Angelo died. It felt like I’d won the lottery for short-order cooks.

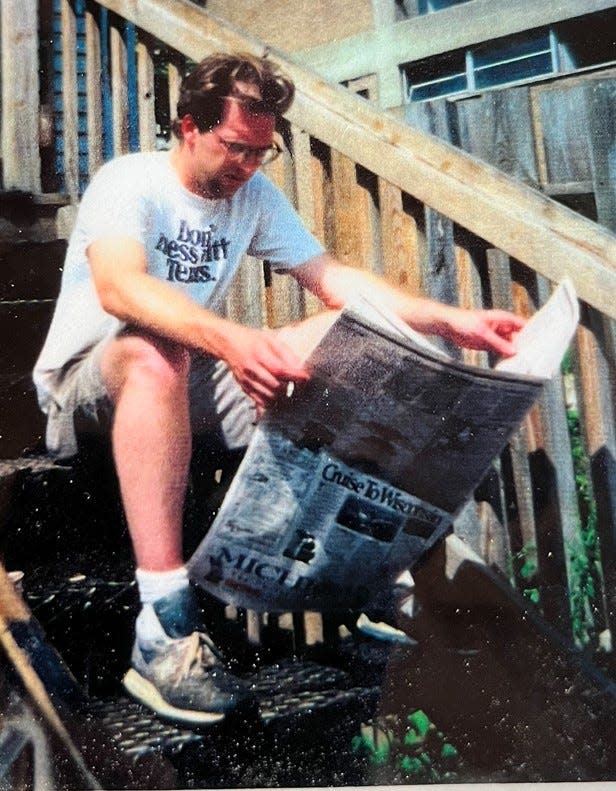

Then the lines started forming, and on some days, they seemed like they stretched forever, snaking through the lobby, out the front door, to the corner, up the side, pooling around the newspaper vending boxes that used to dot the perimeter of so many restaurants.

And if you wanted to drop a quarter in the slot and catch up on the news of the day while you waited, well, you had several choices. Or you could mingle with the group ahead or behind. Say hello. Talk about the weather or the Wolverines or the deep-fried French toast.

There were no cell phones, which was just as well when buried under a sea of handwritten tickets. Distractions were the enemy of organizing the grill, not to mention a path to cutting yourself or burning yourself or, worst of all, overcooking an egg.

When someone expects over-easy and forks into a congealed center? That ain’t the way to survive a line that never ends. Nor is untying your apron, angrily tossing it onto the floor and storming off to the walk-in cooler.

I did that once in the middle of a rush. A weak-kneed lapse from which I had to be coaxed back upstairs by Vangelatos after one too many tirades from my line partner, a talented but ornery short-order cook.

I’d left the line, and my co-workers in a lurch, a DEFCON 1 no-no in the high-pressure industry of eggs benedict and blueberry waffles, cheeseburgers, hash browns and dry — DRY! — egg-white omelets; oh yes, egg-white omelets, a status symbol in those days and a contradictory concoction of veggies and, say, ham, impossible to flip without oil or butter or even a spray of "Pam."

Wide drywall mud spreaders worked best; God forbid a yolk and a little grease.

The customer was always right, though, and in the tensest moments, remembering this simple platitude helped navigate the day.

I thought of that phrase last week when the news broke. I thought about Vangelatos and Juback and all the other family members who helped build Angelo’s into an iconic spot.

I thought about what it means to build a gathering place that can survive endless food trends, adapt through three generations of cultural and technological change, the loss of its founder and a pandemic.

I thought about what it means to embed in a community so long a group of regulars from the early 90s can graduate from U-M, head back east, start careers, begin families, return 30 years later to celebrate their own kids’ graduation from the same university, and take a drive to the corner of Glen and Catherine, pray for a parking spot, and order the exact same dish they did all those years ago:

Hot turkey sandwiches, open-faced and steaming, smothered in chicken gravy.

They were known as the “hot turkey boys,” and when they were students, they came in most Friday afternoons. A few of them reached out to Vangelatos last week, planning a trip for this fall for one last meal, preferably around Ohio State weekend.

“They want to throw a party,” Vangelatos said.

They’ll need to get in line. No, not that line, but the line to mark the end of something meaningful, the line to reflect, to say thanks, to buy a T-shirt — Vangelatos sold 60 of them the day after the sale.

The line to remember where you were when Angelo’s came into your life, and where you are now as it prepares to slip away this December. I’d cooked before I got the job at Angelo’s. I’d written a few freelance pieces, too.

But I didn’t know I could do either until I learned to breathe in the middle of all that heat and pressure, and to find calm in the face of all those tickets.

Contact Shawn Windsor: 313-222-6487 or swindsor@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @shawnwindsor.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Angelo's in Ann Arbor: An institution that taught me how to write