The polar bear plunge: How the Mets landed Pete Alonso with the 64th pick in 2016

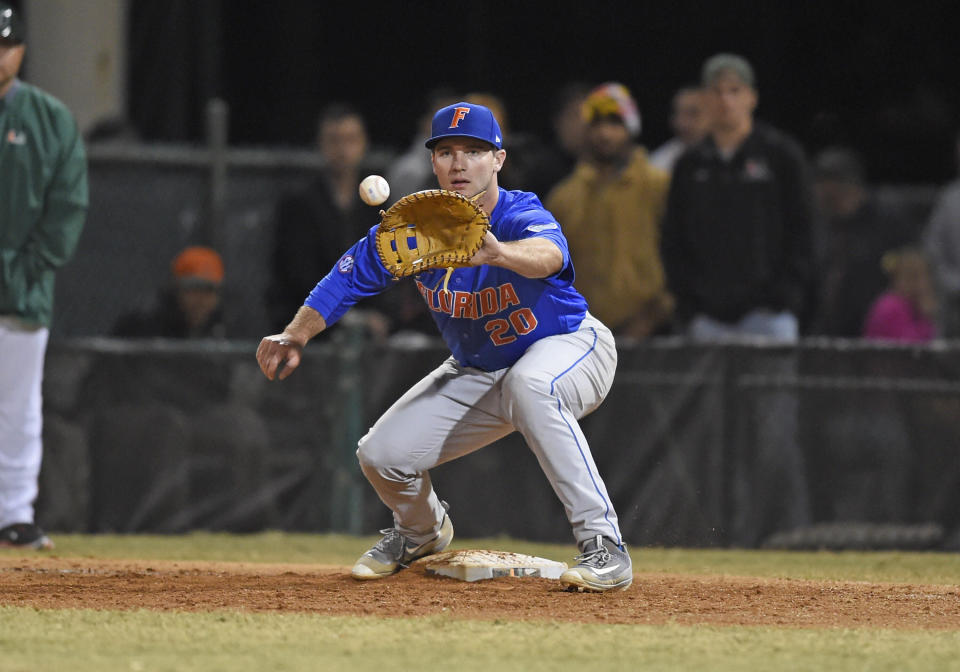

Names kept flying off the board, leaving those in charge of running the Mets draft worried that the powerful slugger from the University of Florida they had been eyeing would soon be gone.

Pete Alonso had impressed Mets scouts for six to seven years now with his work ethic, power, and, yes, some more power, and now those scouts only could wait, hoping he’d fall to pick 64.

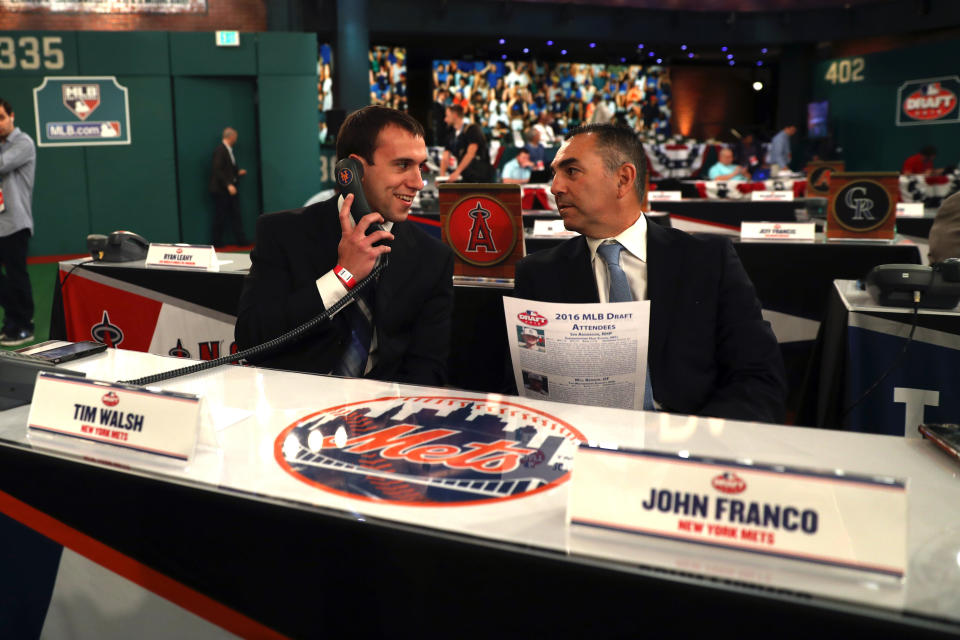

Around the 54th pick, Mets scouting director Tommy Tanous and his assistant scouting director, Marc Tramuta, had decided Alonso was their guy, even if draft history said they could use a later pick.

“Our board blew up quicker than usual,” Tanous, now the Mets’ VP of international and amateur scouting, told Yahoo Sports in a phone interview. “I looked at Tram and asked if he was comfortable taking Alonso. He said, ‘I absolutely am.’ I said, ‘me too.

“We were kind of sweating it out.”

The teams in front of the Mets mostly took position players, but at no point did any of them select the Gators’ righty masher.

Alonso made it to 64, allowing the Mets to keep him in orange and blue, just as the area scout, John Updike, had told Alonso that they hoped to do.

The selection of Alonso has proven to be a potential franchise-changing moment with the rookie emerging as an All-Star candidate and a cornerstone player for years to come.

For the men who played a part in helping Alonso land in Flushing, his success is part of what makes all the hours on the road away from their family worth it.

“There’s no better feeling than watching somebody that all of us played a part in drafting,” Tramuta said. “This was such a group effort. It’s really gratifying.”

MAKING FIRST CONTACT

Steven Barningham has always appreciated the open-door policy at Henry B. Plant High School in Tampa, Fla.

Barningham, now a global crosschecker for the Mets, served as the Mets’ southeast supervisor during Alonso’s prep years, and would stop by Plant HS about every two weeks. The school has produced big leaguers like Hall-of-Famer Wade Boggs and Orioles reliever Mychal Givens.

The scout remembered showing up one day in the early 2010s to watch a potential early-round pick, but leaving that day enamored with a powerful righty.

“There was this underclassman hitting the ball as hard as anybody,” Barningham said.

That underclassman was, of course, Alonso, a third baseman at the time.

Barningham immediately called part-time area scout Les Parker, who had been the first Mets scout to introduce himself to Alonso, and had gotten to know the slugger and his family.

Parker raved about Alonso’s work ethic and his makeup to Barningham, just like he had to Alonso whenever he’d seen him.

“He said he loved watching me play,” Alonso recalled.

The more Barningham saw Alonso, he grew even more fond of the youngster especially since Alonso showcased a hitting skill that is on display quite often now that he’s in the show.

According to Birmingham’s estimations, the right-center fence at Plant is roughly 250 feet from home plate. It breeds pull-happy lefties, and tempts righties who can go the other way.

The ability to go the other way sounds simple, but if it were that easy, there would not be as many shifts as there are in today’s game.

Alonso learned how to go to right-center and take advantage of the short fence.

“That’s what I loved about Pete right away,” Barningham said. “He was trying to hit everything to right-center.”

LANDING A GATOR

While the Mets certainly had interest in Alonso as a high schooler, they and the other 29 teams passed on drafting since they know it would take decent coin for him to forego his commitment to Florida.

Alonso, who enjoyed watching the Florida softball team in the college World Series this past weekend, is happy with the decision he made to attend college.

He blossomed into a top-tier talent during his three years at Florida, and, as Tanous put it, the first baseman checked all of the Mets’ boxes.

Let’s start with the power.

Yes, the power that has him in the same exit velocity conversation with Giancarlo Stanton and Aaron Judge. The power that has him hitting as many homers before June 1 as Mark McGwire did as a rookie. The power that allows him to homer to the opposite field on 98-mph fastballs on the outside corner.

Tramuta compared Alonso’s batting practice to that of a home run derby.

“His batting practice just stood out from everybody else really that I had seen in the past 20 years of scouting,” Tramuta said. “It’s just a different look in how he elevated and how far he hit it.”

What makes Alonso different more than just a slugger, according to Tanous, is his power isn’t just for show. He can utilize it in a game.

He’s not just hitting homers on mistake pitches. He’s a good enough hitter that he can utilize his power on those pitches that aren’t down Broadway.

Alonso also has the uncanny ability to generate his power in short time, which gives him more time to see the pitch. He has a short swing, and when he connects, the ball is crushed. Sometimes, he just flicks his wrists and the ball lands in the stands.

“This was not brain surgery as far as did he have power,” Tanous said. “This is a power hitter with a short swing. It’s a really nice recipe for success.”

During his junior season, Alonso set the record for the longest homer hit at TD Ameritrade Park Omaha, home of the College World Series, breaking the record set earlier in the game by his friend and teammate, Harrison Bader, who is now a Cardinals outfielder.

“Ever since he stepped on campus when he was a freshman, and I was a sophomore, I knew he was a talent. I told everybody that,” Bader said at Busch Stadium in late April. “I know the game so it was a different sound, different look. He had that look. …Just a great hitter.”

Complementing Alonso’s power was his plate discipline.

Tanous and former general manager Sandy Alderson are firm believers that a hitter needs to have a strong eye. Power is great, but if a hitter can’t get on base, that limits that player’s ability to help his team win.

It’s a philosophy that has paid dividends with fellow first-rounders Michael Conforto and Brandon Nimmo, and Tanous and his staff also drafted Jeff McNeil.

Alonso walked as many times as he struck out –31 times – his junior year, and only struck out at a 12 percent clip, a statistic that the scouts still can cite.

“He can get deep in counts and doesn’t chase,” Barningham said. “He’s holding a 12 percent K rate in a league with a 17 percent K rate. For a first baseman, it was unheard of.”

Updike, the Mets’ area scout who covers central and north Florida, noted how Alonso was willing to walk and pass the baton to his teammates if the pitcher didn’t give him anything to hit. And if they pitched him away, he had no problem serving a hit to the opposite field. Alonso has a strong understanding of the strike zone.

“You see how a guy adjusts pitch to pitch, at-bat to at-bat, while they’re trying to get him out,” Updike said. “He’s more than a one-trick pony. He can do many things. We’re seeing that right now at the major league level since he does a very good job of controlling the zone.”

GOING AGAINST THE GRAIN

For as much as the Mets wanted to add Alonso to their farm system, there was one major concern: the draft is not kind to first basemen, especially right-handed hitters.

The general consensus is that teams are better off taking a first baseman later in the draft than using an early pick, and even those early picks are usually lefties.

Freddie Freeman went in the second round in 2007. Joey Votto, the second round in 2002. Eric Hosmer and Adrian Gonzalez both had their names called in the first round.

The Mets actually drafted lefty first baseman Dom Smith in the first round in 2013, and while Smith has blossomed this year, Alonso's emergence likely means Smith will be traded.

Among righties, Paul Goldschmidt waited until the eighth round to be drafted in 2009. Rhys Hoskins fell to the fifth round in 2014. The Angels used a first-round pick on C.J. Cron in 2011, and though he’s been an above-average offensive player during his career, he’s on his third team in six seasons.

“There are some good (early picks), some really good ones,” Tanous said. “But not so much right-handers …We certainly had our concerns with the history of it.”

Ultimately, the Mets had enough belief in Alonso’s abilities as a hitter – that he was more than just a masher — that they were willing to see if could buck that trend.

They knew he would work his tail off to address any shortcomings –especially on the defensive end – and he wouldn’t be an all-or-nothing bat.

Tanous stressed that he and his scouts were all convinced that they were making the right call, and no one objected.

“His ability outweighed the history of the draft,” Tanous said. “If you look at him as a hitter who happens to have a lot of power, that’s how you look at him. …This was a hitter first. This was not a guy we thought would hit .220 with 25 home runs.”

MAKING THE PICK

By the time the draft rolled around, the Mets now had all the information they ever could have needed. All their talks with Alonso’s coaches, from high school to the Northwoods League to Florida, came back clean, reaffirming that he wouldn’t blow his opportunity.

“He was a worker. The thing that stood out the most wasn’t his hitting but his ability to turn himself into a good first baseman, and a defensive first baseman. You got a hit tool, you got a hit tool. Defense is something you can work on,” Bader said. “When he stepped on campus, he wasn’t nearly as talented as he is now. To see him put it all together is great.”

During a May meeting with Alonso, one of two scouting meetings that were allowed, Updike had a simple message for the first baseman.

“I told him I was going to do my best to keep him in blue and orange. I looked him right in the eye,” Updike recalled. “You don’t forget stuff like that.”

Alonso wasn’t sure whether it was just scout speak or a legit preview of what would happen.

“At the time, I didn’t think it really meant anything,” Alonso said. “I thought it was a good sign he likes me as a player. I didn’t think it was going to come to 100 percent fruition.”

The Mets actually passed on Alonso twice before they finally selected him, grabbing Justin Dunn –whom they traded to Seattle this offseason – with the 19th pick, and choosing UConn lefty Anthony Kay, who has been excellent for Double-A Binghamton, with the 31st selection.

Alonso wasn’t in play for either pick, but he had a grade in line with some other first-rounders. The Mets were hot on Dunn’s trail all this year, and he and Alonso are actually close friends.

“Obviously we would have taken (Alonso) with the first pick if we knew he was going to be hitting 40 homers,” Barningham said.

Alonso watched the draft at his Tampa home with his now fiancé, parents and little brother.

Alonso’s agent, Tripper Johnson, called to tell him that the Reds were a possible landing spot at 43, but if the Reds selected catcher Chris Okey, it would clear the path for Alonso to land in New York.

Okey landed in Cincinnati, and Johnson’s prediction rang true.

Alonso still appreciates that the Mets were willing to take a shot on a righty first baseman since he knew that could be held against him.

“The Mets believed in me that much,” Alonso said. “That was extremely special.”

WATCHING FROM AFAR

Scattered across the country, Mets scouts stay in constant connect with one another through a group text.

Nineteen times this year, Alonso has caused one of them – usually Tramuta – to send out an Apple — in reference to the Citi Field home run apple — to the group.

Tramuta includes a screenshot of Alonso rounding the bases when he homered in the Futures Game last year to let them know the Polar Bear hit the bomb.

“You know that guys are spread across the country are watching Pete’s box scores,” Barningham said. “It’s awesome.”

The first apple text came on April 1 when Alonso hit a three-sun shot to dead center at spacious Marlins Park that helped seal a win over the Marlins.

Updike and his wife were at the game, and Updike thought it was a routine out off the bat. But that ball just kept carrying.

“He’s got big time juice,” Updike said. “I’m just so happy for Pete. You realize how hard he works and everything he has overcome to be in this position.''

Ten days later, Alonso hit an Oh-my-God homer into the water in center field at SunTrust Park, a 118-mph rocket that almost broke Statcast.

The homers are coming at what could be a franchise-record pace with Alonso needing 22 more to tie the record set by Carlos Beltran (2006) and Todd Hundley (1996). He should obliterate Daryl Strawberry’s 1983 rookie record of 26 homers.

Alonso’s 19 homers are the third-most in the majors, and he’s hitting .265 with a .940 OPS. The first baseman is a top candidate to be the NL Rookie of the Year.

He’s the classic example of a pick that makes the scouts proud, and one the Mets will be trying to replicate when they pick 12th in Monday’s raft.

“Just the rush you get when you have a player like that, and especially the early success, that’s fun to watch,” Tramuta said. “You hope it continues.”