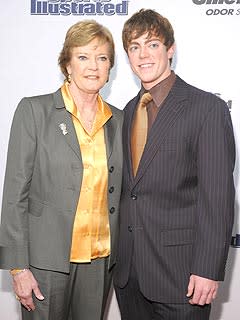

Tyler Summitt battling alongside his legendary mom

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. – Sitting in a conference room in the Tennessee basketball offices, I looked across the table at Tyler Summitt and saw myself.

He’s a more mature college sophomore than I was. Smarter, more polished, seemingly more secure. The son of Pat Summitt was raised in a celebrity coach’s world, where lessons are learned early about how to carry and present yourself. He does those things well.

But beneath the impressive persona is a regular guy with regular-guy problems. The biggest problem: His mom has been diagnosed with early-onset dementia, Alzheimer’s Type.

That’s where I can relate.

In 1984, when I was a sophomore at the University of Missouri, my family in Colorado got the official diagnosis that my mom was suffering from early-onset Alzheimer’s. She was 60 – the same age as Pat Summitt today.

We knew something had been wrong for a few years – not just forgetfulness and confusion, but random mood swings and a gradual inhibition of her effervescent personality. Lynn Forde always was a lot of fun, but that joie de vivre was draining away.

It was good to know what the problem was, but also very bad. Because we knew Alzheimer’s was chronic and incurable.

It took 18 years for Alzheimer’s to finish cruelly killing my mom. She was remarkably healthy physically, so her body kept going long after her mind had been robbed of almost everything. With heavy hearts and great misgiving, we moved her into an Alzheimer’s care facility in 1987 – my father could not sustain the burden of caring for her at home.

The caregivers were wonderfully decent and kind and professional, but Alzheimer’s is undefeated. Nobody beats it.

It didn’t take long before she forgot the names of her three sons, and eventually the name of her husband, our dad. She remembered faces a little while longer, but eventually that was lost as well. The twinkle in her eye was extinguished, replaced by a glassy look of non-recognition for everyone around her. Visits were routinely heartbreaking.

She missed a lot: weddings and births and many other family milestones. I don’t believe she ever read a story I wrote. She died April 5, 2002.

The worst part: Millions of others can tell stories similar to mine.

So when the news of Pat Summitt’s diagnosis was made public last August, a lot of old feelings bubbled to the surface. Most of all, even though I’d never met him, I felt a great empathy for Tyler.

That changed Wednesday. We met in the Tennessee basketball offices, a place Tyler probably knows as well as his bedroom at home. In addition to tagging along after mom since he was a toddler, he’s also a walk-on with the men’s team.

Sitting in the conference room, Tyler said the thing that has impressed him most about his mom was her ability to gracefully handle everything life put on her plate on a daily basis.

[Related: No. 8 Tennessee upset by South Carolina]

“She could do seven things at one time,” he said. “And she always did them the right way.”

One of the signs that something was wrong surfaced when having seven balls in the air became too much. Two or three of those balls hit the ground instead of being handled.

“It’s not that she wasn’t capable of doing things,” Tyler said. “It was that maybe she could only do four things instead of seven. She just wasn’t ‘Wonder Woman’ for a while. We just knew something was amiss.”

That led to a succession of medical evaluations and, ultimately, a diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic. What followed was a significant difference between Tyler’s experience and my own.

The Summitts are going through this with the entire world watching, which can be both disconcerting and comforting.

The hard part was knowing that Pat Summitt’s every move from that announcement on would be viewed through the prism of Alzheimer’s. And snap judgments would be made based on scant information.

If fans saw assistant coach Mickie DeMoss doing most of the talking during a timeout, it must mean that Pat was feeling badly. If the team had a bad game, it must mean that Pat isn’t in charge anymore. And everyone wants to know how long she can and will coach.

“It was obviously the right move, going public,” Tyler said. “Her program’s always been an open book. But it has put a bigger spotlight on this.

“She is still the boss – of the house and of this office. Whatever is going to happen after this season, it’s up to the boss.”

That’s the disconcerting part. The comforting part comes in the form of worldwide support for a woman who has universal respect in the athletics community. Emails, phone calls and texts arrive every day, from friends and family and former players and coaching peers. She has coached so many players and maintained so many great relationships with them that they have flocked to offer support.

“There was an instant explosion of support from around the world,” Tyler said. “It was really comforting to know everyone had her back.”

Fans everywhere have her name on their backs. The “We Back Pat” campaign, to show support for Summitt and raise money for Alzheimer’s research, has become an SEC point of emphasis and a nationwide movement. Tyler was wearing a “We Back Pat” T-shirt when we spoke, and he has his own business cards related to his work with the Pat Summitt Foundation.

He’d like to coach someday, and it’s easy to understand why. He watched arguably the greatest coach in basketball history up-close all his life, and soaked up most of it. Every few sentences, he repeats an aphorism or piece of advice his mom gave him.

But as much as Tyler Summitt has lived a basketball life, the legend he knows is his mom first. She is the woman who loves to cook, loves her yellow labs, loves a boat ride on the Tennessee River, a round of golf in the offseason and a house full of visitors.

“That motherly side is the other side of her,” Tyler said. “It seems like there are always at least two guests at the Summitt house, and they’re going to gain a few pounds eating all the meals and they’re going to sleep great. That’s the other side of Mom.

“I want that family atmosphere to endure. Hopefully, I can be like her in that respect.”

Tyler Summitt is going through this 28 years later than I did. We know a lot more about Alzheimer’s now, and how to treat those who have it. We know how much diet and rest and exercise – both physical and mental – can help. There is a far greater body of knowledge today than in 1984, and a far greater hope.

But there still is no cure.

I was a scared college sophomore then. If Tyler is scared today, he isn’t letting on.

“I don’t focus on what I can’t control,” he said. “We can control the memories we still make together. I’d rather focus on the new memories and the life at hand than worry about losing the past.”

That’s a great outlook, and it should sustain Tyler Summitt in the months and years to come. And hopefully, sooner rather than later, there will be a cure that will help Tyler’s mom. It’s past time for a different ending to a family's Alzheimer’s story.

Editor’s note: For more information on the “We Back Pat” campaign and the Pat Summitt Foundation, visit www.patsummitt.org. For more information on Alzheimer’s disease, visit www.alz.org.

Other popular content on the Yahoo! network:

• Legendary coach Jim Calhoun taking indefinite medical leave

• NCAA Football: Ex-Ohio State coach Jim Tressel takes Akron administrative job

• OMG: Best and worst renditions of national anthem