In shadows of World Cup stadium, neighbors left empty-handed

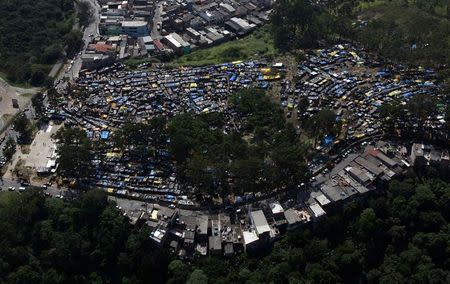

By Brad Haynes SAO PAULO (Reuters) - For Sao Paulo's most popular soccer team, the World Cup has provided a new home after 100 years playing in rented stadiums. Thousands of neighbors, however, say it has left them homeless. They are squatting on land a couple miles south of Arena Corinthians, a glistening white stadium built for nearly 1 billion reais ($450 million) to host six games during the tournament, including the opening match in less than a month. The encampment has grown tenfold in ten days, swelling to more than 4,000 families sleeping in plastic tents and cooking on open fires as they protest against the publicly funded stadium that they say priced them out of their working class neighborhood. President Dilma Rousseff responded swiftly last week, meeting with organizers during a visit to the stadium and promising help. But that did not stop the camp's explosive growth or a wave of related protests revealing deep concerns about the longer-term impact of the World Cup in Brazil. "It's absurd that you're spending a billion reais on a stadium over there and here you've got families under tarps," said Guilherme Boulos, a leader of the Homeless Workers Movement, who promised more protests later this week. "I wish it didn't come to this, but we have no other options," said Regina, an elderly woman waving a wad of burning paper to fend off mosquitoes near recently cleared brush. She watched her family's campsite while her son went to work and her grandsons were at school. "They want you to pay double the rent they were asking a couple of years ago, and now they demand three months in advance. That's what kills you," she said, shaking her head. Up and down snaking rows of numbered tents, protesters echo those complaints about soaring rents - stories supported by public data. Many of them are working-class parents willing to endure the squalid conditions of the encampment to force the mayor's hand for public assistance. Apart from giving the Corinthians club a 48,000-seat home for decades to come, the stadium was supposed to help drive development of Sao Paulo's long-ignored eastern reaches, much as the 2012 Olympics served to revitalize East London. Instead, the huge public investment has raised expectations - and rents - while leaving the question of how to provide crucial public services until after the foreign fans go home. Throughout Brazil, host cities have spared little expense in the rush to prepare arenas for the World Cup, but skimped on the longer-term benefits they promised to ordinary citizens. Officials have cut back, canceled or put off rail projects and bus corridors while dragging their feet on developments around the new stadiums. Brazil is soccer mad and the only country to win the World Cup five times, but support for hosting the tournament fell to just 48 percent last month from 79 percent in 2008, according to pollster Datafolha. Violent protests last year during the Confederations Cup soccer tournament, considered a dress rehearsal for the World Cup, rocked Brazil's government, which is concerned about more people taking to the streets in the coming weeks. The housing protests in Sao Paulo are part of that broader frustration. PROMISES Officials opted to build the brand new World Cup venue for Sao Paulo despite already having a 65,000-seat stadium on the city's verdant west side. The new stadium in the city's gritty eastern outskirts is being built with the help of state-subsized credit and fiscal incentives. [ID:nL1N0JQ1G4] Officials promised it would help accelerate development in the surrounding Itaquera neighborhood along with a new business district, cultural centers, courts and other public services. Those projects are still just promises. State and municipal governments have plowed nearly $250 million into new avenues, overpasses and other public works improving access to the new stadium. But the only public facility on the newly developed land is a technical college serving as a base of operations for world soccer body FIFA. "I believe in a period of at least two to three years we can install most of the other facilities," deputy mayor Nadia Campeão said in an interview. "It wasn't possible to advance much without improving accessibility and circulation." However, the original development plan was also scaled back and now the health clinic and courthouse will be built elsewhere, as well as a proposed police headquarters and fire station. One concern was game-day traffic in the area - and the antics of notoriously rowdy Corinthians fans. Public land by the stadium will be used for vocational training, a cultural center and a children's museum. The promise of 50,000 new jobs will hinge on development of a former quarry behind the stadium, which could become an office park with new public incentives. Marcos Lindenberg, a partner in the private development, said he was in early talks with companies and he could see construction over the next three to five years. HOUSING DEFICIT Public works may be slow, but the housing market is not. Spurred by the stadium, new roads and the prospect of more to come, rents nearly doubled in Itaquera in the year after the stadium was announced, according to economic think tank FIPE. "You can't even afford the favelas around here," said Maria Ivete dos Santos Dias, 49, referring to the slums that ring the city. She used to rent for 50 reais per month when she arrived in the adjacent Jardim Helian neighborhood a decade ago. Last year, the rent bill jumped from 200 reais to 350 reais - half what her daughter earns at a diner while she takes care of four grandchildren. So they moved out of the two-bedroom home their family shared with three others and into a tent with just as much space to themselves. Dias was part of the first few hundred families that launched the occupation in a lot that has sat empty for decades. Since then, the camp has grown up a hillside and into a grove of trees as others joined from surrounding neighborhoods. Rapid development in Itaquera has aggravated soaring rents city-wide. Average property values in Sao Paulo tripled since 2008 due to government stimulus and broader access to credit. Decades of under-investment have left Sao Paulo with a housing deficit of over 200,000 new homes, but officials say Itaquera is not the place to build them. Sao Paulo's east side has a third of its population but just a sixth of its jobs. The city's mayor, Fernando Haddad, is pushing for affordable housing downtown and more businesses in outer boroughs such as Itaquera. That means higher rent, the deputy mayor conceded, adding that rising property values are good news for the homeowners who helped build the neighborhood as they arrived in recent generations. Renters stranded by the rising tide have grown the ranks of the Homeless Workers Movement. The group is one of many housing rights movements in Sao Paulo that have occupied over 100 vacant lots and buildings in the past year. "If you can't pay rent anymore, you're not able to spend 10 years on city hall's waiting list for a housing lottery," wrote Raquel Rolnik, a special rapporteur to the United Nations on housing and professor of urban studies at the University of Sao Paulo, in a recent essay published to her personal website. "The World Cup is a global showcase for sponsors and host cities, but it's also a showcase for those calling attention to social issues the country faces." (Reporting by Brad Haynes; Editing by Kieran Murray)