Raucous lifestyle leads to fall of Jeff Rubin, former financial adviser to NFL players

DOTHAN, Ala. – Premium parking was easy to find on a hot, muggy day in late May at Center Stage bingo casino. In a sea of almost a thousand parking spaces, just 52 cars sat in the lot.

Inside, the view was drearier. Electronic bingo games were played on silent computer monitors, giving the casino all the excitement of a doctor's waiting room. The adjoining restaurant was an empty, out-of-business shell. The places where a high-end bar and a club were originally supposed to be were either locked up or cast in shadows.

[Related: Terrell Owens, others say Drew Rosenhaus' negligence contributed to lost millions]

Part of the bingo hall was partitioned with an odd black wall featuring flecks of light shimmering through. On closer inspection, the "wall" was actually a bunch of spray-painted plywood sheets patched together.

Customers wore T-shirts and paint-splattered jeans, and the Southern drawl of the man talking over the PA system made the room like a scene from a Jeff Foxworthy routine.

Yet for a group of 35 current and former NFL players, Center Stage is no joke. Raided by Alabama state authorities in July and stripped of its "illegal" bingo computer monitors, the casino is now down to hosting paper bingo – the final shred of economic life in a business that's part of a bankruptcy filing including $68 million in losses, including as much as $43.6 million from NFL players.

Even with the bingo hall's adjoining amphitheater, bed-and-breakfast and RV parking lot on the property, the question that plays on a loop is simple: Where did all the money go?

At the center of the question is Jeff Rubin, who at one time operated one of the largest financial adviser firms in the NFL. Some players came to trust Rubin more than a decade ago when he saved them from a Ponzi scheme involving then-NFL player agent Tank Black.

Rubin – who declined to comment for this story on at least 10 occasions through attorneys, relatives, and friends – is still living in a $2.8 million home on the water just north of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and driving a Mercedes 550 luxury sedan. According to multiple sources and financial documents, Rubin made millions off the players' investments in the casino operation.

Rubin's fall featured more than its share of warning signs, Yahoo! Sports has discovered after a five-month investigation. By about 2005, he was regularly spending $40,000 to $50,000 a month on his corporate credit card with Pro Sports Financial, the company he founded. Seven years later, he's living in the house with a bodyguard and security cameras.

Hero to zero

Rubin attended the University of Florida with future NFL players like Fred Taylor, Reidel Anthony and Ike Hilliard. That was his initial entry into the sports business after he made friends with Gators players like Errict Rhett and Mo Collins.

Rubin, who graduated from Florida in 1997 with a degree in exercise and sports sciences, cemented his relationship with the players when he helped expose a $15 million scheme Black was helping run, one of the biggest scams in NFL agent history at the time. Black eventually went to prison and was driven out of the business. The players received some or all of their money back.

"[Rubin] was a hero to those guys, he helped them," said Peggy Lee, who managed the office at Rubin's firm, Pro Sports Financial.

However, the players and others around Rubin appear to have ignored numerous red flags of troubling behavior as time passed. In 2003, former Rubin client and NFL linebacker Barrett Green hired someone to privately look at Rubin's handling of his money after Green discovered a discrepancy. Green eventually reported the problem to his agent, Drew Rosenhaus, but Rosenhaus continued to work with Rubin. Green retained Rosenhaus, but fired Rubin and told Y! Sports that he eventually recouped his money. Rosenhaus refused comment on the matter.

In 2004, Rubin settled a Financial Industry Regulatory Authority complaint filed by former client and NFL linebacker Johnny Rutledge. Rutledge claimed that several signatures on an insurance document that cost him $119,000 were not his. Rubin settled the issue for $40,000 without admitting or denying responsibility.

Rubin's personal life also raised questions. In July 2005, his on-again, off-again fiancé, 21-year-old Elizabeth McClure, died of a drug overdose after she mixed crack cocaine, prescription medication and alcohol, according to the Broward County medical examiner's report. In September 2011, Rubin and assistant Mike Kneuer were arrested on the casino property on charges including possession of marijuana, Xanax and a substance local police believed was GHB. The charges against Rubin are expected to be dropped after he completes a pretrial diversion program he agreed to on Aug. 13. Kneuer is also expected to have the charges dropped after both he and Rubin left Dothan and resigned their positions with the casino.

[Yahoo! Sports Radio: Jason Cole on Drew Rosenhaus not receiving money from bingo venture]

Before then, Rubin purchased the $2.8 million home in Lighthouse Point, Fla., in June 2005 and acquired two high-end cars, a Mercedes 550 sedan and a Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder, the second car leased for $153,000. Rubin did all of this while running a business that included at least 45 NFL players as clients that Y! Sports was able to confirm. Former Pro Sports Financial vice president Mike McIntyre said the company represented more than 100 clients at its peak.

Subsequently, 35 players lost as much as $43.6 million in the failed casino operation, according to filings with the Florida Secretary of State and bankruptcy documents in the case. Evidence in a July 2011 Alabama gambling corruption trial also showed the FBI was investigating the casino operation.

Among the players who have lost money in the casino are Taylor, Jevon Kearse, Terrell Owens, Plaxico Burress, Clinton Portis, Roscoe Parrish, Gerard Warren, Kyle Orton, Greg Olsen, Santonio Holmes and Santana Moss. Numerous players have filed lawsuits against law firm Greenberg Traurig, which allegedly set up investment vehicles for the players.

Drew Rosenhaus and his brother Jason, who is also an agent and works with his brother, had 26 common clients with Rubin at one time or another. Both said they were surprised by Rubin's rise and fall.

"Jason and I always thought that Jeff would do things the right way because of the fact that he had a tremendous client base," Drew Rosenhaus said. "Players wanted to hire him and it would seem crazy to [screw] that up. It was the only thing that he had, to my knowledge."

As a former Rubin employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said: "At the company's height, [Rubin] was probably making $700,000 or $800,000. If he had just maintained the business, he could have made $500,000 a year for a long, long time. You can have a very good life on that kind of money."

In 2011, Rubin spoke to Y! Sports on several occasions about the casino operation. However, after returning to Lighthouse Point this year, Rubin has repeatedly declined to talk to reporters. In August, attorney Patricia Morales Christiansen of Palm Beach said Rubin had stopped paying her.

Pipeline to players

While attending the University of Florida, Rubin turned a chance encounter with Rhett at an airport into an opportunity to get close to other Florida football players. According to McIntyre, Rubin roomed with Collins and tutored other players.

Rubin's big break came when he discovered Black's financial indiscretions. While playing for the Jacksonville Jaguars in 1998, Taylor returned home to find his luxury house had no electricity. The power had been turned off because Taylor's bill had gone unpaid for months by Black.

Rubin, who had begun a career as an insurance salesman with Northwestern Mutual in South Florida, discovered that Taylor's money, along with that of many other athletes, had been rerouted into an offshore account. Black was investigated, eventually went to prison and was drummed out of the agent business.

Rubin's assistance in the discovery helped him gain the immediate trust of some of the NFL's top young players. And he had just enough financial training to take advantage of that trust. Rubin and McIntyre eventually formed Pro Sports Financial, a concierge financial service that took care of nearly every need for a player, from insurance to bill paying to even running errands.

In the 1999 NFL offseason, Rubin rented a home in South Florida's exclusive Golden Beach community. Players such as Taylor, Kearse, Burress and Samari Rolle lived at the house as they trained and partied during the offseason.

Rubin's insurance business helped him profit. Because life insurance policies are generally one-time sales rather than a renewable, yearly policy, insurance companies give brokers a chance to take their commissions on the policy right away.

In essence, on a $10 million policy, a broker may receive a commission of $150,000. With certain insurance companies, the broker can choose to take as much as $120,000 of the commission in the first year. Even if the policy eventually lapses, the commission is already paid.

"If you sold a life insurance policy, sometimes you'd make $80,000 to $100,000 on one life insurance policy on commission," McIntyre said.

"It's really a bad deal for the insurance company in the short-term because the company has to maintain the coverage for seven or eight years even if the premium hasn't been paid," a source who is familiar with both Rubin's business practices and the insurance industry said. "It's a bad deal for the player in the long-term because just when he really needs the coverage, the policy lapses … the guy who is making out is the broker because he got all his money up front."

Not surprisingly, four players told Y! Sports their life insurance policies had lapsed. One player said he repeatedly asked Rubin about the policy, but was told by Rubin that the policy would "take care of itself."

After Rubin left Northwestern Mutual, he brought Lee and McIntyre with him to start what eventually became Pro Sports Financial. The early years of the company were halcyon times. The company grew quickly and Rubin was considered a power broker.

Moreover, Rubin had what many considered a strong relationship with many of the players. Kearse, for instance, was seen as a true friend to Rubin, not just an athlete using him for a service.

When approached at his ocean-front home in Pompano Beach, Fla., Kearse declined to elaborate on the situation with Rubin because of pending litigation. Three sources said Kearse invested at least $1 million in the Alabama casino project, although his attorney Andy Kagan declined to comment. Kagan represents approximately 20 players who were involved with the casino and other investments overseen by Rubin. However, Kearse admitted he and Rubin were close friends at one time.

"I'm just learning about a lot of stuff now," Kearse said.

The housing play

As it turns out, Kearse's mini-mansion on the water is another example of how Rubin made money off players.

In June 2005, Rubin bought a 4,739-square foot "McMansion" in Lighthouse Point, just north of Fort Lauderdale. The home is typical of the nouveau riche-style that that has taken over the area. Older Florida-style vacation homes that were built in the 1960s and 1970s have been torn down and replaced with oversized, zero-lot-line houses (Rubin's house is built on a quarter-acre lot), complete with a pool and a place to dock a boat in the backyard.

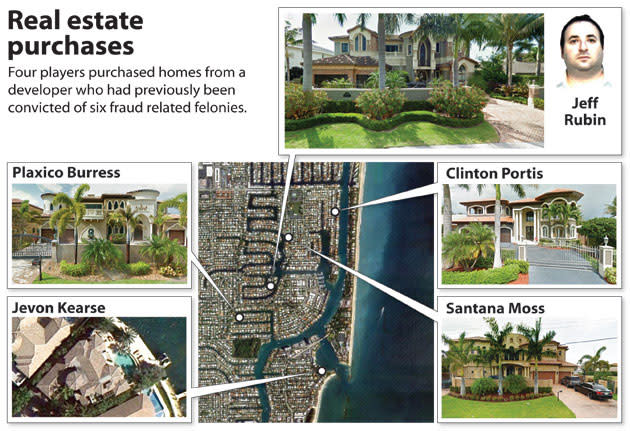

By March 2006, Kearse, Burress, Moss and Portis – all Rubin clients – had purchased similar homes in Lighthouse Point or the surrounding area.

However, Burress' house cost $3.99 million, Portis' house was $4.1 million, Moss spent $5.2 million and Kearse topped the group at $6.1 million. Although comparative pricing is difficult for these homes because they are relatively new on the market (they were all built around 2005), Rubin's house sold for $2.8 million despite being comparable in size and structure to the houses purchased by Burress and Portis. The house Moss bought was more than 9,000 square feet and Kearse's house sits on an ocean-front.

All of the homes were built by Michael Friend of Remi Properties. McIntyre said that Rubin negotiated with Friend to receive a discount on his home by convincing the players to buy their homes.

"They kind of worked out a deal for those … prices, it brought down the price for Jeff's house," McIntyre said. "That's how [Rubin] got his house."

A second source with knowledge of the transactions confirmed that. In addition, two South Florida real estate agents with experience in forensic price analysis said the purchase prices on the five homes and the subsequent decline in their respective values raised questions about the houses' initial pricing. The value of Rubin's home, which he is currently living in, has dropped roughly 24 percent, compared with roughly 60 percent drops for the other four homes.

"There were a lot of games played with houses in that area," said one of the real estate agents who declined to speak on the record because he had not seen the homes personally.

The homes of Burress, Moss and Portis have either been subject to foreclosure proceedings or sold at significant loss. Kearse is still living in his home, but multiple sources said they expect he will eventually lose it. Kearse refused to discuss the matter.

Friend also refused to speak in-depth about his relationship with Rubin. Before becoming a builder, Friend twice filed for bankruptcy and was convicted six times on fraud and/or other economic crimes.

"I'm trying to rebuild my life after all of that," Friend said before hanging up.

Spinning out of control

Rubin was considered a recruiting dynamo in the early years of Pro Sports Financial, a man who could overcome his un-athletic looks. In the macho, alpha-male culture of the NFL, the dumpy Rubin somehow fit. Part of it was his reputation built on saving players from the Tank Black days. Part of it was his hubris, a striking sense of confidence that fit the culture even if he didn't measure up physically.

"Our clients were mesmerized by this guy," Jason Rosenhaus said.

McIntyre, Lee and others who knew Rubin from the business said there was a "Rubin Factor," a polite and humorous way of describing his boastfulness about anything from how the business was doing to how he was doing in his dating life.

One employee said that as time went on, that factor morphed from humorous to reckless.

"He started to believe his own lies," the employee said. "It went from something somewhat funny, a wink of an eye or a laugh, to a way to sell everybody that things were going to be OK."

McIntyre and others said Rubin would continually surround himself with women, which impressed players.

Jason Rosenhaus was blunt when describing Rubin's dating life: "He picked bad women, I think. Just seeing him with women, [it] was a problem with him. He never once was with a nice girl who cared about him. He was always with sluts who were into money. He was handing [out] money and being a flashy guy. He had the Napoleon syndrome to the 10th degree."

Eventually, Rubin's focus on Pro Sports Financial fluctuated. After the early days of hard recruiting, Rubin progressively turned that part of the business over to underlings. He hired Mike Rowan and Jason Jernigan as recruiters around 2003. Rowan and Jernigan were immediately successful.

"[Rubin was] like, 'You know what? The business is running itself. I can kick back and party and hang out with the girls, meet girls, buy a big house on Lighthouse Point,' " McIntyre said.

However, Rowan and Jernigan eventually broke off and started their own company, Capital Management Group Wealth Advisors, before getting into trouble themselves .

The pair left the same week that McClure died, adding to Rubin's stress and shock, Lee said. In the short-term, Rubin again focused on the business.

The focus didn't last long. By 2008, Rubin became a regular at Automatic Slims, a nightclub in Fort Lauderdale. After the club closed, Rubin borrowed money to become a part-owner and re-opened the spot under the name SHO. The club didn't last long and neither did Rubin's financial stake.

By 2010, Rubin would go months without showing up at the Pro Sports Financial office and weeks without returning phone calls, Lee and McIntyre said. The firm's client list began to erode.

Lee said some employees took pay cuts as the company's income started to dry up. She said she eventually had to take money out of her own pocket to buy office supplies to keep the company running from day-to-day.

McIntyre said he could see the writing on the wall about the company heading south. Despite his seemingly critical statements about Rubin, he repeatedly said he's not bitter. Rather, McIntyre said he enjoyed the ride while it lasted.

Even when it headed to the Deep South.

Alabama is calling

At roughly the same time that Rubin was investing in his nightclub, developer Ronnie Gilley was recruiting investors for his bingo casino project. Gilley fashioned the idea from Victoryland, a bingo casino, hotel and greyhound track project that Milton McGregor opened near Montgomery, Ala., in 2008. Victoryland featured 1,700 bingo machines and was projected to bring in more than $100 million annually. McGregor even became one of Gilley's top single investors.

Most of Gilley's early investors were not athletes. He eventually met Cornelius Griffin, a defensive tackle who played 10 years in the NFL and was with the Washington Redskins at the time. Griffin grew up in Troy and attended the University of Alabama.

The idea for athletes to invest in the project germinated in the Washington locker room with fellow Redskins players such as Moss and Portis getting involved. They eventually introduced Gilley to Rubin.

Gilley began flying Rubin and many of the players on private jets from Fort Lauderdale's Executive Airport to see McGregor's casino in Montgomery and then down to Dothan to see the land where the new casino would be built. McIntyre said Rubin was enthralled by Gilley's presentation.

"It would have been a huge operation, big money coming in," McIntyre said. "[Rubin] was like: 'This is it, we're all going to retire and make tons of money off this deal. We're going to be able to cash out. This is going to be it right here.' Big expectations, I was excited … I was going to move to Dothan, Alabama. I'll do whatever you need to do. [Pro Sports Financial] was kind of dying out and hopefully we were going to make money from this here.

"We would have been a small shareholder and get percentages. So I was like, 'OK, this would be good retirement for me,' and I'd have residual income for as long as it is open. Jeff talks a big game. It's very easy to believe in this stuff. Once the whole project came along, Jeff stopped recruiting guys."

A player who spoke on the condition of anonymity described the trip from South Florida to tour McGregor's casino: "They took us around the casino, to the hotel and then into the back room where all the money was. It was a real-deal casino and the cash was back there in giant stacks."

The NFL has strict prohibitions on players and other league personnel investing with gambling operations. In addition, bingo in Alabama is only supposed to be a charity operation. Some money is allowed to be taken out of the gross to cover expenses, but the law in the state is relatively strict.

The way around those prohibitions was by using a loophole. Technically, the players were not investing in the casino. They were investing in the land the casino sat on and the building in which it was housed. The players were then going to lease the space to the casino operation, creating an expense that could be deducted from any charitable earnings.

However, the most significant problem was, as the subscription agreement specifically noted, that electronic bingo may not have been legal in Alabama at the time. McGregor was skirting the law in Montgomery and a second casino project was even more problematic.

"The Country Crossing Project [which later became Center Stage] and its future plans are dependent … [on] Ronnie Gilley Properties, LLC and its affiliate companies to conduct electronic bingo operations which may be characterized as illegal gambling under Alabama law," the agreement read.

At least two people associated with Rubin and Pro Sports Financial said they advised Rubin against the investment.

"He disregarded what I said," one of them said.

Worse, the players said they were never informed that electronic bingo was illegal in any way. When Owens was asked whether he was informed of potential legal problems with bingo, he said via text message, "Absolutely not." Two other players said they were never informed that electronic bingo was illegal. Both said they would not have invested in the project had they known.

Rubin clearly knew of the problem. He participated in a viral marketing effort to make it appear that gambling had more support in Alabama as Gilley worked to get electronic bingo legalized. During the July 2011 gambling corruption trial, Gilley testified that when pro-gambling articles appeared on different media websites in the state, he and McGregor paid a marketing firm to add comments at the bottom of the articles to make it appear that there was strong support for gambling in the state.

Gilley then admitted during testimony that the marketing firm was run by Rubin.

By the middle of 2011, Pro Sports Financial shut down. Lee said she received a call from Rubin saying the company was going to close. On the final day, as everyone left the office, the players' files, including their tax information, were sitting in boxes on the floor.

"I just called him to tell him all this stuff was here and we didn't know what to do with it," Lee said.

Rubin was too caught up in the casino operation and had plenty of incentive to secure money. Gilley agreed to give Rubin a 4 percent stake in the casino operation for bringing in investors, according to bankruptcy documents. In addition, Gilley gave Rubin a 10 percent "finder's fee" on any money he brought in. In essence, Rubin was getting a polite version of a kickback on what the players put in, according to paperwork possessed by one of the attorneys.

According to a source with knowledge of Gilley's transactions, Gilley made several large deposits into accounts belonging to Pankas Holdings. That is a corporation formed by Rubin, according to documents acquired by Y! Sports.

But just as the doors to the bingo casino were opening in 2010, the project was about to unravel. That year, Alabama authorities, pushed by then-Governor Bob Riley, raided the casino in Dothan and McGregor's Victoryland operation. There were two other attempts at raids that year in Dothan, but the casino was able to get an injunction or shut its doors before authorities arrived.

Gilley was eventually arrested and charged in 2010 on numerous counts of bribery, conspiracy and money laundering. Gilley eventually pleaded guilty to 11 counts. During interviews with Y! Sports in 2011, Rubin said that Riley's ties to the Mississippi Choctaw Indian gaming interests pushed Riley to close down the casinos (the Choctaw's reportedly donated $13 million to Riley's campaign in 2002). However, Alabama's war on the casinos continued after Riley was out of office (Robert Bentley was elected governor in 2010).

The state has upgraded its laws against electronic bingo to make it a felony to even transport a bingo machine into the state. During the raid of Center Stage in July, authorities seized all the bingo machines and the state attorney general's office is now pushing to have them destroyed.

After Gilley was arrested, Rubin tried to salvage the casino operation. He moved from South Florida into the bed-and-breakfast hotel on the casino property. Time and again, he promised players and their attorneys that he would get their money back to them, according to sources.

However, after Rubin was arrested in September 2011 on the drug charges (authorities also said they were investigating a charge of sexual assault), his days in Alabama were numbered. By the end of 2011, Rubin left the casino operation.

For the time being, Rubin now lives back in his ornate, Renaissance-style home on the water, living off the money he allegedly made from Gilley and the players. Some of the players still talk to him. Others have written him off as a bad experience and are just hoping to get their money back.

Other popular content on the Yahoo! network:

• Flames: RG3 is about to drop bombs on the Bayou

• Donovan McNabb accepts reality, moves toward a career in broadcasting

• Donovan McNabb accepts reality, moves toward a career in broadcasting

• Shine: White House releases Obama's beer recipe