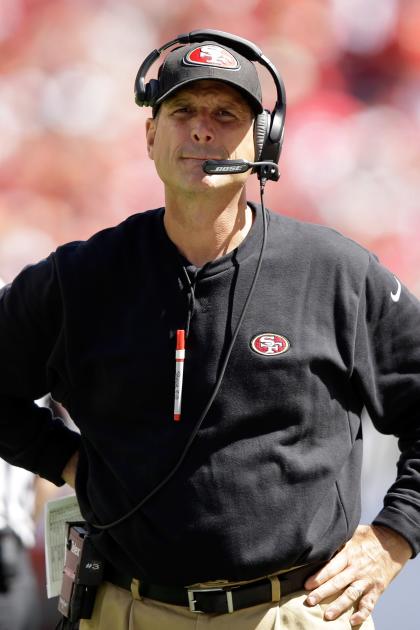

Jim Harbaugh's biggest challenge yet with the 49ers

Jack Harbaugh always told his kids the same thing: "Attack this day with an enthusiasm unknown to mankind!"

That saying has been ingrained and passed down, all the way to dozens of players and coaches in the Harbaugh orbit, from coast to coast. The lesson is about looking for the positive, even if the positive has to be unearthed from within.

It's gotten Jim Harbaugh to the NFL as a quarterback, to a BCS bowl victory as a head coach and to the Super Bowl as the man in charge of the San Francisco 49ers. It's a special kind of fire-and-brimstone phrase, now linked to the famous son of the old football coach.

Now, though, that Harbaugh verve is being challenged in a daunting new way.

Star linebacker Aldon Smith has been suspended nine games for personal conduct and substance abuse violations. And only days after NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell's lengthy letter on domestic violence, defensive lineman Ray McDonald was arrested after police reported "visible injuries" on his pregnant fiancée.

There are other on-field problems: NaVorro Bowman, Glenn Dorsey and Kendall Hunter are all injured, and Pro Bowl safety Antoine Bethea suffered a concussion during the preseason. But it's the legal turmoil that looms largest. A man who has always gotten by with enthusiasm finds himself under intense scrutiny regarding a matter that demands complete sobriety.

His brother responded poorly when confronted with a similar situation. Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice was seen on surveillance cameras dragging his fiancée out of an Atlantic City elevator during the offseason, and Baltimore coach John Harbaugh leapt to his player's defense without stopping to denounce the act of domestic violence. John Harbaugh is a good leader, a Super Bowl winner, and yet in that reaction he was reduced to something less inspiring. His support was tone deaf, and cringe-inducing.

Jim Harbaugh has been more circumspect. In his news conference on Wednesday, he compellingly described two important principles: refusal to tolerate domestic violence, and the support of due process. Both of these principles are crucial to our society, so it's to Harbaugh's credit that he mentions them in the same breath. The alleged victim, as a member of the NFL family (and as a human being), deserves more than lip service. McDonald, as someone who has been accused but not convicted, deserves some protection from a rush to judgment. But if McDonald remains with the team and plays on Sunday against the Dallas Cowboys, it's hard to see how Harbaugh or the 49ers are refusing to tolerate domestic violence. Harbaugh called for "information and facts" as the basis of his decision, yet he probably has a good amount of information and facts already. He could bench McDonald without any withholding of pay until the information and facts come in, and still honor both of the principles he mentioned.

What complicates this, and surely gnaws at Harbaugh, is that part of the equation is his experience with McDonald. He said more than once on Wednesday how long and how well he'd known his player, and it's clear his relationship with McDonald is at stake here. If Harbaugh benches McDonald, it's a show of non-belief, or at least will be interpreted that way. The effects of that decision might not ebb over time, and would become deeply entrenched if McDonald is absolved of this accusation. And there could be a spillover too, as every player in that locker room is watching to see how the head coach reacts.

Meanwhile, in the wake of the Goodell edict, the football community is looking to Harbaugh to see how he'll treat this very delicate situation. If he doesn't come down harshly, the league's tougher stance doesn't look as tough, and the Niners look like enablers. There's also Harbaugh's place in the team hierarchy. He is not calling all the shots; there is general manager Trent Baalke and owner Jed York, as well, who have powerful voices here. It's Harbaugh, though, who is being monitored the closest.

This problem is more acute in Harbaugh's case than it might be elsewhere in the league. Bill Belichick's reputation is not built on enthusiasm. His reputation is that of the cold calculator, getting rid of Wes Welker or Randy Moss or Logan Mankins without an apparent worry. Part of Harbaugh's buy-in is his energy – the emotional power that his dad taught him to show even under the trickiest circumstances. Here, Harbaugh cannot lean on passion in the same way. If he's incensed at McDonald, it's an affront to due process. If he's sympathetic to someone he clearly cares about, he might be coddling a criminal and ignoring the plight of an abused woman.

Emotion has always pushed Harbaugh along. It made him an icon at the University of Michigan, well before quarterbacks regularly jumped to the NFL from that school. It made him Captain Comeback as a passer with the Colts, before the modern era of magic-making quarterbacks in Indianapolis. It galvanized a lesser-known program at San Diego, after he became head coach there, and it gave Stanford a new identity that still lasts years after he left. One of the key moments in his coaching career was when he had his tête-à-tête with then-USC coach Pete Carroll at midfield after a game, yelling "What's your deal?" when Carroll asked the same question. At the next level, there was the overaggressive postgame handshake with then-Lions coach Jim Schwartz. In both cases, fan bases (and probably players) got a charge out of the head coach jutting that lantern jaw out in defiance. Jim Harbaugh could overcome anything with that fire of his.

There is far more to overcome now. He led his team to the Super Bowl, only to face the unprecedented situation of facing the brother who heard the same advice from father Jack. Then the Niners returned to the brink of a championship in 2013, only to lose to Carroll, the old nemesis whose sunniness has so far been unblemished in Seattle. In both games, Harbaugh's team came within a whisper of winning. The coach was left with two offseasons of wondering if a certain play might have cost a championship.

His job now is to cajole his players through another season in which that one play will define everything – unless they don't get that close again. Even if the Niners are as good as they've been, it won't be truly satisfying to anyone until January or later.

For now, heading to Arlington, Texas, for Week 1, there are many pitfalls to the season: the injuries, the age of running back Frank Gore, the underwhelming (borderline unwatchable) play of backup quarterback Blaine Gabbert and the looming cloud of off-field issues that threaten to make a historically immaculate franchise into a West Coast version of the Cincinnati Bengals.

Don't forget the odd contract limbo hanging over him and the team: Harbaugh may earn a long-term deal … or he may no longer coach in San Francisco after this season.

Oh, and then there are the Seahawks.

Harbaugh gets no sympathy, wants none, deserves none. He's a millionaire living his dream and coaching in the NFL. Yet his obstacles are uniquely difficult. He'll need an enthusiasm that feels familiar to his players, fresh for a new season, and also tempered in the eyes of those waiting for him to say the wrong thing. He'll need a collegiate enthusiasm that still comes across as especially professional.

That kind of enthusiasm might not be unknown to mankind, but it's pretty hard to come by.

More NFL coverage: