Where have you gone, Mr. September?

Editor’s Note: This story originally was published on Sept. 1, 2016 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Harry Gant’s magical September winning streak in 1991. The 2021 race at Richmond marks the 30th anniversary of Gant’s win as part of his four-race winning streak.

Just months before, the seemingly timeless Nolan Ryan had twirled his seventh no-hitter at the age of 44. Tennis star Jimmy Connors was days into an unlikely, age-defying run into the U.S. Open semifinals at 39.

In 1991, the sports world’s well had been primed for feats that defied both logic and the limits of advancing years. The NASCAR world was no different.

The time was right for 51-year-old Harry Gant.

RELATED: Our picks for Driver by Number | Harry Gant through the years

By the 1991 season, the veteran driver already possessed a handful of nicknames to choose from:

• “Hard-Luck Harry,” a label he finally shook by collecting his first premier-series win (1982, Martinsville) after finishing second a heart-wrenching 10 times.

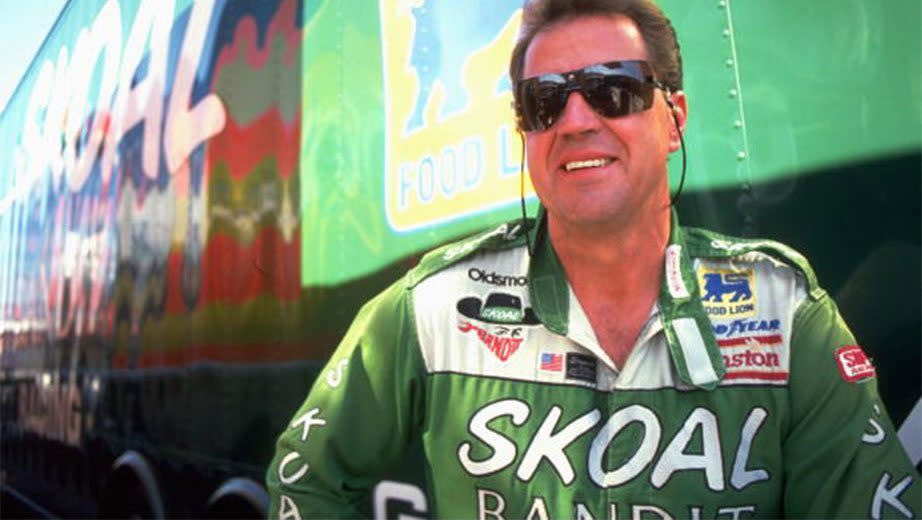

• “The Bandit,” a nod to Gant’s longtime sponsorship from U.S. Smokeless Tobacco’s Skoal brand.

• “Handsome Harry,” his best-known alias, which owed to the matinee-idol good looks that followed him into grandfatherhood.

But 25 years ago this month, Harold Phil Gant earned another affectionate handle for his most notable accomplishment in stock-car racing’s big leagues — a history-making, four-race win streak at age 51 that transformed him into “Mr. September.”

Other drivers with Hall of Fame credentials have amassed wins in fours since the dawn of NASCAR’s modern era in 1971, but other factors beyond his age make Gant’s performance a singular achievement. Gant also won twice in what is now the NASCAR Xfinity Series during that magical September, leaving him a streak of six straight national series triumphs. He won all four premier-series races with the same car — a Leo Jackson-owned No. 33 Oldsmobile Cutlass — and same engine at all four tracks.

“We’ll probably run it until we wreck it,” Gant said back then. The car was involved in two crashes during the four-race romp, but never lost its winning edge.

The phrase “better with age” was Harry Gant defined. He won eight Winston Cup races after the age of 50, a run that made his Skoal Bandit banner a frequent flyer just underneath the American flag at the Alexander County courthouse in his hometown of Taylorsville, North Carolina.

Gant still calls the town of nearly 2,100 residents home. Though he hung up his driving gloves after the 1994 season, he’s far from the formal interpretation of retirement. From sunup to sundown, Gant can be found either raising cattle and raking pastureland on his 300-acre farm or mowing neighboring solar farms with his grandson.

Taking time out to recall the details of his extraordinary record? When his daughter, 55-year-old Debbie Pollard, answers the phone in Gant’s nondescript Taylorsville office, she says he’s simply far too busy. Maybe when the grass stops growing later into October, she says, pointing out a small window to chat this weekend in Darlington.

“That might be a good place to catch him,” Pollard says.

Twenty-five years ago at Darlington, no one could. In the three magical weeks that followed, Gant’s No. 33 was just as uncatchable.

In the spirit of celebrating NASCAR’s throwback history this weekend, NASCAR.com takes a race-by-race look at Gant’s stunning surge to four wins in a row — and the chance for a fifth that barely slipped away.

DARLINGTON: Sept. 1, 1991

The race: Gant’s hot streak actually took root away from the race track with a Wednesday victory in a driver-invitational golf tournament. Gant qualified fifth for the Heinz Southern 500, but alterations by crew chief Andy Petree had brightened his driver’s outlook on an otherwise cloudy day.

In front of Gant on the starting grid were points leader Dale Earnhardt, going for his third consecutive Southern 500 win, and Davey Allison, who started from the pole position and dominated the early portions of the Labor Day classic. Gant didn’t take the lead until the 151st lap, but once there, he placed cars a lap down at a rapid clip.

Allison loomed as Gant’s closest competition — he ended the day leading 151 laps to Gant’s 152 — but a broken throttle spring doomed the No. 28 Ford’s chances. With his throttle intermittently sticking, Allison barreled into Michael Waltrip, sending the latter into a spin and bringing out a caution period with 70 laps to go.

Gant led the rest of the way, winning by 10.97 seconds and leaving just two other cars on the lead lap. Down the stretch, ESPN anchor Bob Jenkins remarked that Gant was “not getting older, he’s getting better” — a theme that pit reporter Dr. Jerry Punch picked up on in his Victory Lane interview.

“For 51 years of age, you look fresh as a daisy,” Punch said.

Gant, who savored the last of his four career Darlington victories, replied: “Well, I feel good. I figured that was the only way I was going to beat ’em today was just wear ’em out. They may be younger, but I can wear ’em out.”

What was different: The frontstretch and backstretch were flip-flopped, with the start/finish line still on the side closest to the Harry Byrd Highway. Pit road also was separated into frontstraight and backstraight lanes, a huge disadvantage for cars forced to pit last.

Silly season moves: Darlington weekend began with news reports of Geoff Bodine reaching an agreement with car owner Bud Moore for 1992, leaving the Junior Johnson-owned No. 11 team after two years. Bill Elliott, later tapped as Bodine’s replacement, rattled off his own four-race win streak early in the ’92 season.

Race runner-up: Ernie Irvan, the Daytona 500 winner that year. Irvan won twice in 1991 and wound up fifth in the overall standings — the highest points finish of his premier-series career.

RICHMOND: Sept. 7, 1991

The race: Gant had never won back-to-back races in his career, but carried high hopes after a Busch Grand National victory at Richmond Raceway, which had freshly installed lights for its first weekend of night races. Gant quipped after winning the 200-lap preliminary that the track’s switch pushed his celebration past his bedtime.

Gant had questioned Jackson, his car owner, about bringing his Southern 500-winning car to Richmond, hoping to save the familiar No. 33 for the following weekend at Dover. Jackson won the debate, and Gant had that familiar seat for the Miller Genuine Draft 400.

A TBS broadcast crew, which remarkably included NFL great Ken Stabler as a commentator and pit reporter, watched pole-starter Rusty Wallace and Davey Allison rule the early stages while Gant bided his time. By the three-quarter mark of the 400-lap race, Alan Kulwicki and Ernie Irvan came to the front to stage a spirited duel for the top spot.

That battle went sour with 88 laps left when the two front-runners collided. Gant, running third, tried to avoid the spin, but turned into the path of Morgan Shepherd and lost control. Gant looped his car and kept going, actually gaining second place in the aftermath.

The fracas allowed Allison to take control, but his grasp on the lead wasn’t a firm one. Gant reeled in the Robert Yates-owned No. 28 to lead the final 19 laps.

“We’ve been having a lot of fun the past couple of weeks,” Gant said after scoring his only premier-series triumph at Richmond. In Victory Lane, Gant received a prolonged peck on the cheek as he posed for post-race photos with a trophy girl. As Gant smiled, someone shouted: “He’s a grandpa. Not on the mouth.”

What was different: Besides making the transition to nighttime racing, Richmond also featured a pit-entrance wall perilously close to the racing groove in Turn 4. The abutment has since been moved farther away from the preferred racing line.

Silly season moves: After Dale Jarrett righted the Wood Brothers No. 21 Ford from an early spin, TBS lead broadcaster Ken Squier remarked about the future NASCAR Hall of Famer: “Of course, next year he’s one of the big stories, moves on with the coach of the Washington Redskins to form a new team. Joe Gibbs will come out here with an organization. That oughta be something.”

Race runner-up: Davey Allison, who led a race-best 150 of 400 laps. The second-generation star finished the 1991 season with five victories and a third-place ranking in the Winston Cup standings.

DOVER: Sept. 15, 1991

The race: With another Grand National victory in the books as a Saturday prelude, Gant entered the Peak Antifreeze 500 at Dover with a ton of momentum. The grandstands were catching on, too, with the Gant faithful sporting pins reading, “Life Begins at 51.”

The fans’ rally of support for the veteran Gant prompted 49-year-old Dick Trickle to quip: “The older you get, the better you get. If I was Harry’s age, we probably could’ve won.”

The Monster Mile took a heavy toll on the field that September, snaring 15 cars in a Lap 70 melee on the backstretch. Three more hopefuls bowed out just past the midpoint when pole-winner Alan Kulwicki’s engine faltered, leaving himself, Dale Earnhardt and Rusty Wallace tangled up in the No. 7 car’s dropped oil. Several more teams succumbed to crashes and mechanical woes, leaving just 16 of the 40 cars running at the finish.

Davey Allison was again Gant’s prime challenger, but after leading the first 114 laps, the engine expired on his No. 28 Havoline Ford. Allison actually continued in a brief relief stint for the ailing Kyle Petty, who missed 11 races that year after suffering a broken left leg in a crash that May at Talladega Superspeedway.

With Allison added to the lengthy attrition list, Gant poured it on, leading all but four of the final 330 laps. His only nuisance down the stretch was a warning light on his dash, indicating a potential hiccup with his car’s alternator. Rather than make a lengthy stop to remedy the issue, Gant said later that he simply unscrewed and discarded the bulb on his Oldsmobile’s dash.

Gant’s performance left little doubt to the outcome, but his excellence left the TNN broadcast booth in awe. “I can’t believe what I’m watching,” said NASCAR Hall of Fame nominee Buddy Baker. “This guy acts like there’s nobody out there but him; the rest of ’em are just traffic, you know?”

By the end, the rest of the field indeed was traffic. Gant finished on a lap by himself, a feat that’s only happened once since (in 1994 with Geoff Bodine at North Wilkesboro).

“I thought yesterday was an easy win, but today was even easier,” Gant told reporters afterward. “It just sat there glued to that race track.”

His plans to celebrate the victory in the days that followed stayed true to his working-man upbringing. “Finishing up some garage doors and just moving some dirt,” Gant said. “I may not be the best race driver, but I’m a good carpenter.”

What was different: Dover has always been known as a punishing venue, but the Monster Mile hosted grueling 500-mile events up until the 1997 season, when the track reduced its race distances by 100 miles. The September 1991 race clocked in at 4 hours, 32 minutes. In 1991, the track also used an asphalt surface, which was replaced by concrete in 1995. Dover Downs International Speedway also dropped the “Downs” part from its name in 2002.

Silly season moves: Baker mentioned during the broadcast that Hall of Famer Bobby Allison had turned laps in testing at Martinsville Speedway earlier in the week. Though the session fueled speculation for a NASCAR comeback, Allison would not race again after his severe crash at Pocono Raceway in June 1988.

Race runner-up: Geoff Bodine, who held off Morgan Shepherd in a closely contested battle for second place over the final five miles. Bodine, who led just two of the 500 laps, exclaimed in post-race interviews: “Can anyone beat Harry Gant?”

MARTINSVILLE: Sept. 22, 1991

The race: With a growing buzz in the grandstands focusing on Gant, ESPN broadcasters Benny Parsons and Ned Jarrett previewed the Goody’s 500 from beside his car. By then, the two TV analysts had retired from their racing days, but it didn’t stop both of them from showing up at Martinsville Speedway in their fire suits, playfully begging Gant for a chance to drive the No. 33 Oldsmobile that had become a fountain of youth.

Gant methodically worked his way to the front from the 12th starting spot, bypassing Rusty Wallace to take the lead for the first time in the 196th of 500 laps. Though Gant set the pace for a race-high 226 laps, his path was not nearly as trouble-free as at Dover the week before.

In a contest for the lead after a Lap 376 restart, Wallace nudged Gant into a spin in the .526-mile track’s third turn. Gant’s No. 33 sustained significant front-end damage after third-place Morgan Shepherd became involved, but the 51-year-old drove away from the stack-up.

The amount of torn-up sheet metal and smoke around the No. 33’s nose seemed terminal, at least to Parsons. “Looks like that right-front tire is going south and the car is going north,” he said. “Pretty heavy damage to that car, so Harry Gant will not win his fourth in a row, I’m sad to say.”

Gant had fallen out of the top 10, but made a fierce charge to prove Parsons wrong. Gant said later that he “ran about 10 laps as mad as a bull,” the hood of his battered Olds held down by bungee cords and the right-front fender peeled away.

On the ensuing restart, Gant deftly jumped back up to ninth place, causing Parson to doubt his proclamation. When Gant slipped past Terry Labonte for third, Parsons was beside himself: “This is unbelievable! I crossed Harry Gant off. I said he’s not going to win four in a row, and I don’t know — he just might still do it.”

By Lap 448, Gant had come all the way back to the top spot, passing Ernie Irvan and Brett Bodine to take control. After being bumped out of the lead by Bodine one lap later, Gant capitalized when Petree & Co. made quick work of his final pit stop, winning the race off pit road and staying out front the last 47 laps.

“I figured we had it in the bag, but then I realized how many laps were still left, and I knew it couldn’t be this easy,” Gant told reporters later. “… It sure is special. I don’t even know what to say about all this anymore.”

What was different: Martinsville Speedway’s curbs in the corners have endured, but in 1991, the pit road was split into separate lanes on the frontstretch and the backstretch. The entire area was rebuilt in 2008, creating one contiguous pit lane. Like other short tracks of its era, the 1991 starting lineup had a scant 32 cars.

Race runner-up: Brett Bodine, who faded down the stretch with a broken exhaust and worn brakes. Bodine, now NASCAR’s pace car driver, held on to secure the final top-five finish for a Buick in stock-car racing’s top series. “If it means winning races like Harry, I’ll say I’m 51 right now,” Bodine marveled post-race.

NORTH WILKESBORO: Sept. 29, 1991

The race: The final Winston Cup race of the month offered Gant a chance at more history: An unprecedented five-in-a-row streak in the sanctioning body’s modern era. North Wilkesboro Speedway was at a fevered pitch, the .625-mile track nestled just 20 miles away from Gant’s hometown in the next county over.

“I think we’ve got a home-track crowd, but I don’t think there’s any advantage for this car today,” Gant told ESPN’s Dr. Jerry Punch in interviews just before the start of the Tyson Holly Farms 400.

Qualifying indicated a clear-cut edge, with Gant netting his first pole position in more than four years, ending a dry spell of 126 races. His lap was just .004 seconds better than second-fastest Davey Allison, who was granted permission to go first in the qualifying order so that he could attend a wedding that Friday evening.

Gant sailed effortlessly from the start, placing all but 11 other cars a lap down before the race was even 100 laps old. He led the first 252 of 400 laps before surrendering the top spot to Morgan Shepherd in a pit-stop exchange. Just 41 laps later, Gant had reassumed the lead as the anticipation built for a potential September sweep.

But the No. 33 car that had been seemingly indestructible for the stellar four-race stretch finally developed a weak point. A faulty brake line caused Gant’s car to lose fluid for the final run to the checkered flag, allowing points leader Dale Earnhardt to close in.

Gant couldn’t hold on, and Earnhardt worked his car around on the high side with nine laps remaining. ESPN’s Ned Jarrett remarked: “First time that Harry Gant has been passed in how long?” Benny Parsons, his colleague, told lead announcer Bob Jenkins: “I feel like there’s not going to be Christmas this year.”

Off camera in Victory Lane, Earnhardt — who had assembled his own four-race sweep in 1987 — cracked: “I didn’t want ol’ Harry breaking my four-straight streak.” More significantly, the win provided a boost to his lead in the series standings, an edge that Earnhardt would carry to his fifth championship at season’s end.

Gant simply shrugged at his misfortune and managed a smile: “I was outrunning them down the straights and coasting through the corners. But with a driver like Earnhardt behind you, that won’t work for very long.”

What was different: Second-day qualifying, which allowed drivers to try to improve upon their first-round times. Earnhardt used the rule to improve his starting position from 28th to 16th in Saturday’s qualifying. NASCAR officials abandoned the next-day session after the 2000 season.

Silly season moves: Petty Enterprises made plans for a news conference, scheduled two days after the North Wilkesboro race. At the Oct. 1 media availability in Level Cross, Richard Petty ended weeks of speculation by announcing that the 1992 season would be his last as a driver.

Race runner-up: Gant, who led 350 of the 400 laps before settling for second place. Gant later reflected on the impact of his September stretch, saying that his official fan club membership rose roughly 20 percent that season. “That was probably the best thing about the streak,” Gant said, “just the support of all the fans.”