Walking RI: Rare Atlantic white cedars still dot the trails of a Cumberland preserve

CUMBERLAND – Atlantic white cedars are a rare sight in Rhode Island and getting rarer.

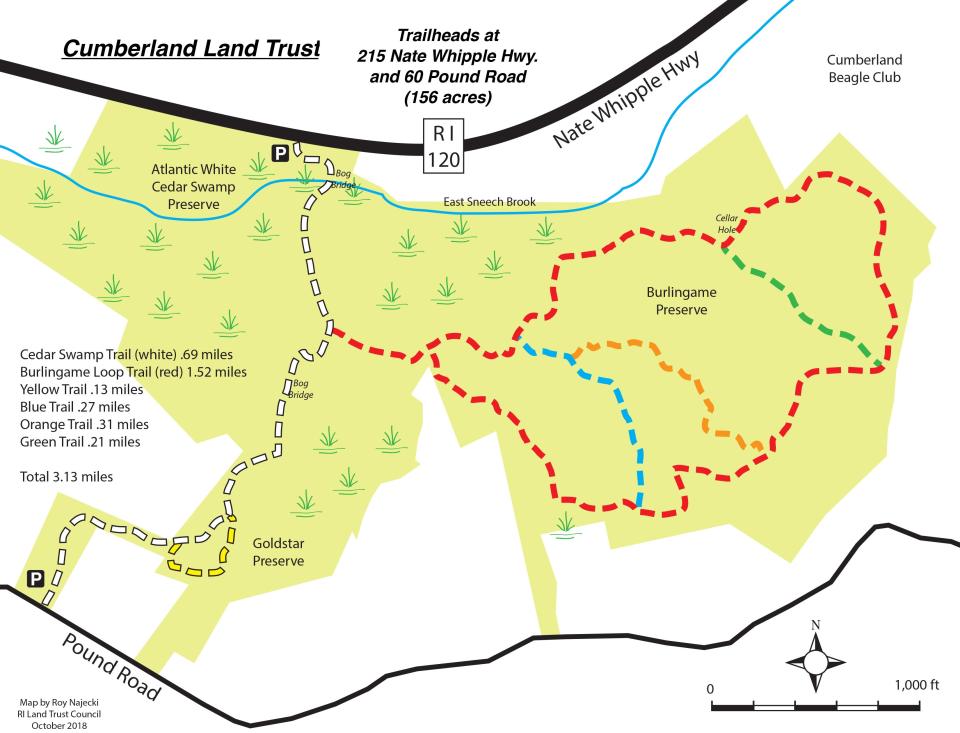

I felt lucky to see a stand of the trees when I hiked through the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp and Gold Star, James Bland and Burlingame preserves, a cluster of contiguous parcels managed by the Cumberland Land Trust.

The cedars are an important part of Rhode Island’s forest because they provide a valuable nesting habitat for various birds, and white-tailed deer are fond of nibbling the tree’s foliage.

I learned later, however, that many of the trees in the swamp are dead or dying from recent extreme cycles of flooding, stormwater runoff and drought.

While there are still plenty of Atlantic white cedars in several parts of the state, it’s sad to see any of them die, deteriorate, fall into the swamp and disappear.

I found the trees along winding trails that crossed several bridges over wetlands and a swamp in the four-property, 153-acre collection of preserves.

Besides the white cedar trees, the preserve has a network of trails that wind by stone walls, old roads, woodlots and pastureland cleared by Colonial farmers and a cellar hole linked to a “poor house” built in the 1800s. It’s a good walk.

I set out from the trailhead on a wide, white-blazed trail and passed a sitting bench, several yellow birdhouses hanging high in the trees and a sign that reported that foxes, rabbits, squirrels and owls live along the color-coded trails.

Just ahead is a bridge and long boardwalk over East Sneech Brook, which flows east from the swamp and eventually empties into the Pawtucket Reservoir.

Signs of beavers at work

If you look to the right from the bridge, you can see a sign depicting an old beaver dam. The beaver activity expanded in 2015, resulting in dams and 6-foot-high beaver lodges – round mounds built of mud, twigs, sticks and branches. The structures flooded the swamp, blocked a culvert and damaged the Atlantic white cedar trees that are visible to the west.

To the right of the sign is one of several “beaver deceivers,” pipes and wire fencing that the land trust built to channel the water under the beaver blockages and carry it away from the swamp. In addition, several trails were rerouted and the boardwalk was erected over the deepest sections of water.

A sign posted on the bridge explains the effort to control the beaver activity and flooding and includes a detailed wetland management permit from the state Department of Environmental Management.

Past the bridge, the trail turns rooted and rocky for a short distance and passes an outcropping on the left. On the right is a side spur that leads to the rim of the swamp and a closer look at the beaver lodges. In the distance, the Atlantic white cedar trees, which usually grow in peaty or mucky soil, taper to a cone with a fan-like spray of blue or green-tinted leaves. The trees tend to grow along the coast, usually within 100 miles of the Atlantic Ocean, from southern Maine to Florida.

Back on the path, the white-blazed trail intersects with the red-blazed trail, which I took to circle the perimeter of the preserve. The path crosses a long, wooden plank bridge elevated on cut logs that runs alongside a stone wall. At a fork, I took the left branch of the red-blazed trail that parallels the Nate Whipple Highway for a while. After a couple of hundred yards or so, a grove of white cedar trees on the left stands between the highway and the path.

At one point, the trail runs up and down small hills and then along a high ridge with wetlands down below to the left.

The high ground is part of the Burlingame Preserve, named for Earl J. Burlingame and his family, who settled in Cumberland in the 1700s. The original family holdings once extended from Mendon Road to Diamond Hill Plain.

The Cumberland Land Trust purchased 84 acres from Debra Podgursko, a granddaughter of the Burlingames, who wanted to preserve the land from being developed.

Passing by the 'Poor Man's' house

Continuing on the red-blazed trail and after a junction with a green-blazed trail on the right, I passed a rectangular cellar hole that I measured at about 15 feet by 27 feet and 6 feet deep.

Michael Boday, vice president of the land trust and a director since 20025, told me it’s called the “Poor Man’s Foundation.” It was named for a poorhouse that Cumberland established in 1830 on the grounds of what is now Cumberland High School. The poorhouse was set up under a state law that required that “overseers of the poor have the care of all indigent persons settled in their respective town and shall see that they are properly supported in such ways as the citizens of the town may determine or at the discretion of the overseers.”

The cellar hole once supported a house for the men from the poorhouse, who harvested surrounding trees to heat the poorhouse, Boday said.

After thinking about that and inspecting the cellar hole, I continued on the red-blazed trail as it curled through a second-growth forest on what looked like land that was once cleared for woodlots and pastures. I also noticed parallel stone walls that once marked the now-abandoned Colonial Road, which dates back to the 1700s and ran about a mile from Pound Road to Little Pond County Road. Hikers have found deep ruts and tracks left from the wagon wheels.

I continued on the red-blazed trail that passed through thick forests and by lowlands and a small pond where insects skittered across the surface. As I approached, a frog jumped from a lily pad into the shallow water.

I followed the mostly flat trail west, climbed over a downed tree, reached the junction I had passed earlier and again crossed the long, wooden plank bridge by the stone wall. When I came to the white-blazed trail on the left, I took it south and over a wooden bog bridge engraved with CLT 2018, the date it was built.

The West Sneech Brook rushed underneath and ran toward the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp.

The swamp, which has expanded in recent years, is filled by streams from Cumberland Reservoir overflow.

Fall is here: The ultimate guide to autumn in RI

After the trail climbs a small hillside, a side spur on the left loops through the 38-acre Goldstar Preserve, land donated as part of the requirements to build a nearby development. Other land in the preserve was acquired from descendants of James J. Bland, a local landowner.

A little further along, the spur returns to the white trail and I could see houses and fences through the trees on the right. I heard a rooster crow. The path turned wide and grassy, passed a row of vertical pipes with yellow caps marking a gas line easement and ended at a trailhead at Pound Road.

I turned and retraced my steps. I had a little more time, so I headed back to the red blazed trail and took three connector trails marked in blue, green and orange before heading back to the trailhead on Nate Whipple Road.

In all, I hiked about 3.5 miles over two hours, with plenty of stops to study the swamp and the Atlantic white cedar trees. I’ve seen similar trees along the Mill Pond Trail in Charlestown and in other preserves. It’s good to know there are still healthy stands of the trees, but it’s a bit depressing to learn that we can’t save them all.

If you go ...

Access: From Route 295, take Route 114 north. Turn left on Route 120 (Nate Whipple Highway) and the trailhead is across from Sneech Pond Road.

Parking: Available along the road.

Dogs: Allowed, but must be leashed.

Distance: 3.5 miles

Difficulty: Easy, with some moderate climbs over ridges

GPS Coordinates: 41.9782324, -71.4402914

Lectures and Signings for “Walking Rhode Island” book

John Kostrzewa’s new book, “Walking Rhode Island 40 Hikes for Nature and History Lovers with Pictures, GPS Coordinates and Trail Maps” is available at local booksellers and at Amazon.com. He’ll sell and sign books after these presentations and slideshows about his hikes:

Tuesday, Oct. 10: Barrington Public Library, 6 to 7 p.m. Register at: tinyurl.com/8td5a2kk

Saturday, Oct. 14: Cumberland Land Trust annual meeting, Cumberland, 10 a.m.

Wednesday, Oct. 18: Narragansett Public Library, 6 p.m.

John Kostrzewa’s column runs every other Sunday in The Journal’s Rhode Islander pages. He welcomes email at johnekostrzewa@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Rare Atlantic white cedars dot the trails of a Cumberland preserve