Seve's final interview: 'It is tough when you see that the end is coming'

Severiano Ballesteros is weeping. The tears do not come gently, but in a torrent, in a sudden epiphany about what it means to die.

Alone in this vast house above the Bay of Santander, there is too much time for Ballesteros to contemplate his own mortality. He claims he could never live anywhere else, and when you see the walls of the local clubhouse plastered with his picture, when you pass the tumbledown farm building where he was born, you start to see his point.

But Pedreña, the place he once described as "my paradise", harbours too many memories for comfort. Frail and emotionally fragile, he wanders through the rooms of the house alone, his three children having left to live with their mother Carmen, Ballesteros's wife of 16 years, in Madrid. His doctors have counselled that he needs peace, rest and the salty sea air to recover from the ravages of brain surgery. They did not mention solitude.

It is at an early stage during this, his only major newspaper interview since his 18-month ordeal began, that a sense of helplessness, a raw fear about not being able to support his family, first manifests itself. I have asked about what he would like for Javier, his 19-year-old son, who apparently has his heart set on emulating his father's exploits in professional golf. "All I want from Javier is to be a good person," he says, before dissolving in heaving sobs.

I am asked to leave the living room. Ivan, Ballesteros's nephew, who acts as his manager and protector, comes out after a few minutes to make a plea. "He gets very emotional when talking about the family," he explains. "I know you have to go through these questions, but please try to make it easy for him."

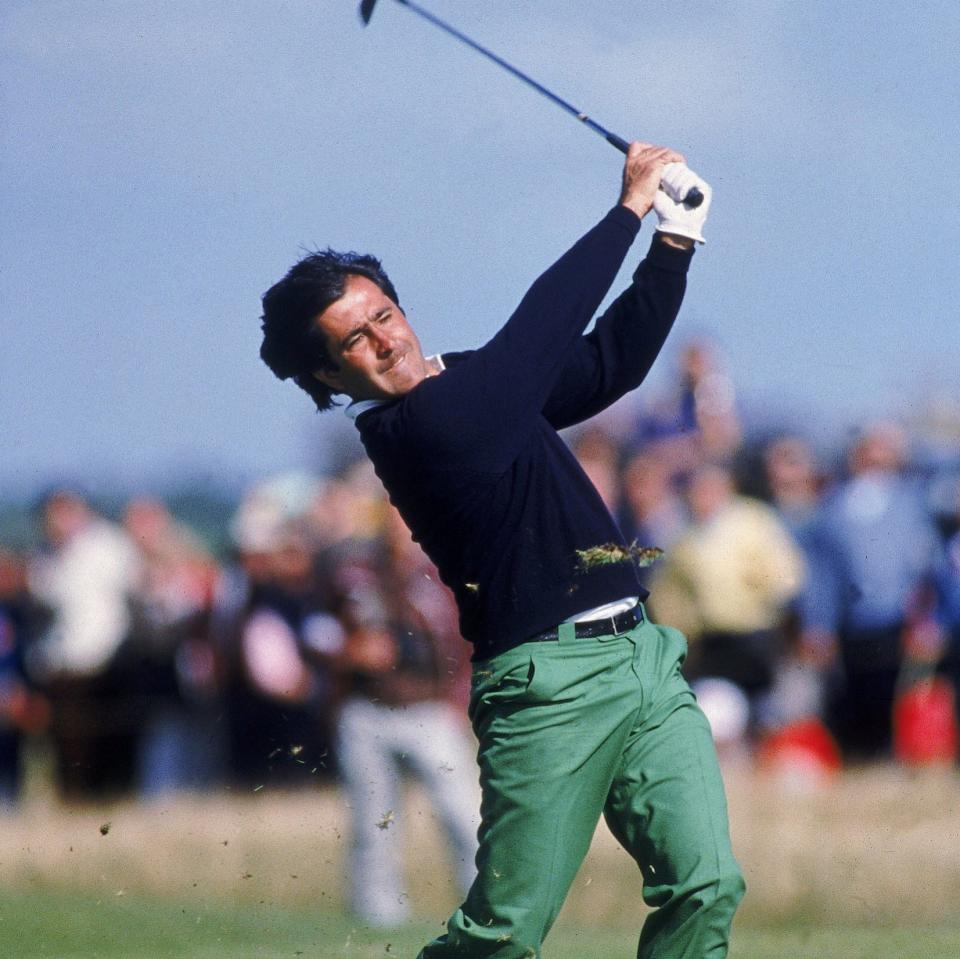

For a while longer I remain in the hallway, glancing at a portrait of the young Seve in his most iconic pose: navy-blue sweater, clenched fist, open mouth, roaring in happiness of his Open victory at St Andrews 26 years ago.

Ballesteros, it is hard not to conclude, was the Rafael Nadal of his day, a richly expressive Spanish heart-throb who became beloved among a British audience as much for his idiosyncrasies as his talents. Audacious to the point of reckless, he combined power – a product, mainly, of his experience in hitting off the pebbles of Pedreña beach with wooden-shafted clubs – with outrageous, instinctive short-game touch.

Nadal has claimed that the latest generation of Spanish sports stars, himself included, are the country's greatest, but Ballesteros prefigured all of them. David Villa could score the winning goal for Spain in Sunday's World Cup final, but will it ever become known as El Momento?

This is the label given by Ballesteros's inner sanctum to his 15-foot birdie putt on St Andrews' 18th green, which sealed his second Open triumph and provoked his unforgettable, arms-aloft jig for joy. A silhouette of that defining moment from the summer of 1984 is mounted in bronze on the front door, which he has opened on a hot afternoon to let in the breeze from outside. A matching tattoo even features prominently on his left arm. Echoes of his past are everywhere; the pathos is almost painful.

Ballesteros, at 53, wanted desperately to return to the scene of his greatest accomplishment next week, competing in the four-hole Champions Trophy that the Royal & Ancient Golf Club is staging to honour their finest Open winners. But two weeks after our meeting his specialists advise him against the trip. The rapturous reception that would be his right would, they argue, be too draining, too disruptive to his convalescence.

He knows it, too, judging by the romantic sense of longing in his words. As he puts it, "One thing is my intention and another is what the doctors will say." He is passionate in his desire to come, but mindful of the likelihood that it will not happen. "I love St Andrews as much as my house, as much as Pedreña," he says. "It's like going back home." Then Ballesteros points to one of umpteen canvases of the Auld Grey Toon.

"You see St Andrews there, but over the top of my bed is an even bigger picture of '84, of when I holed that putt to win the Open and beat the best player in the world at the time, Tom Watson. There were so many people who supported me the whole week, and showed me how much they loved me. To win the Open is one thing, but to win at St Andrews is something different. It's a piece of art; a unique, singular place. I really believe the Open should be there every year."

His logic owes much to the love he felt from the multitudes who watched him, captivated by his invention, his improbable escapes, his interaction, his looks, his sheer mystique.

"I love the British people. They made me feel like I was at home, like I was their son. It could not have been better treatment, it's impossible. I will never forget that." They have not forgotten him, either. Ballesteros may be physically enfeebled but the correspondence that has poured into Pedreña since the fateful hour on Oct 5, 2008, when he was diagnosed with a brain tumour the size of two golf balls, is colossal. "My family couldn't believe how many messages of support we received. I didn't read them one by one, but Ivan, my nephew showed me the amount. It was incredible."

Jack Nicklaus was among the sympathisers, inviting Ballesteros to be the guest of honour at last month's Memorial Tournament in Ohio. That journey, too, was ruled out on health grounds, but if anyone could appreciate the poignancy of an Open homecoming, it was Nicklaus. The greatest player of all time was cheered at every turn by 50,000 people at St Andrews five years ago, for his final major.

Images of Nicklaus striding jauntily up the 18th fairway that Friday afternoon, missing the cut but drinking in the acclaim all around, are indelibly inscribed in Open folklore. There was only one spectacle that could eclipse them for significance: that of Ballesteros, visibly diminished but still defiant, standing beside the bridge over the Swilken Burn.

It is heartbreaking that it shall not now come to pass. Ballesteros, barely out of his hospital bed, was first attracted to the notion of a St Andrews comeback last July, when he watched Tom Watson revive days of yore at Turnberry. He could scarcely credit that his former nemesis came within one errant eight-footer of winning a sixth Open, aged 59.

"I feel very sorry about that missed putt for Tom. For me, the champion of that Open was Tom. He did everything to win, but golf is an unpredictable game. He was a great inspiration to me. That was when I thought about going to St Andrews. He brought me that desire and determination.

"St Andrews, you see, is unique: the road hole, Hell Bunker, the museum, the hotel, the shops in the town where everybody is selling golf – all of it. I want to spend time with the people there. They want to see me, and I want to see them. It's an appreciation."

Ballesteros had toiled to be in a fit state to mount the tee next Wednesday evening, hitting up to 70 balls a day in his back garden, irrespective of his physiotherapist's advice to treat his body with care. The scars from his 22 days of intensive care, followed by another 50 days of recuperation at Madrid's La Paz hospital, are vivid. A long diagonal scar, from where the incisions for four major operations were made, runs across his scalp, visible through his thinning hair.

A partial paralysis also persists on his left side. "I don't see 70 per cent with my left eye. If I look this way," he says, tilting his head to the left, "I don't see you. Normally I should see you, no? I have a problem in my left hand – even though I hit balls, I don't feel very well in the fingers. I have lost the touch, the sensitivity. It's the same with my left leg. I'm not perfect yet."

Just how far he is from perfect becomes clear by the wistfulness with which he looks at life after St Andrews. His patent vulnerability, and the urging of his doctors not to venture beyond Pedreña, are not happy signs. "Who knows? It is like playing a lottery. It's difficult to tell."

The balmy weather at least helps to soothe him, after a winter on the Costa Verde that brought 50 straight days of rain. "It has been a tough winter here, so thank God we are in the summer. My recovery has been good thanks to my brothers, my nephews and my sons. They give me positive energy. Family is the most important thing in life. Family, friends and a good job, especially in these times."

Suddenly, an explanation appears for his acute concern about Javier, his eldest, who is in the first year of training to be a lawyer. "If he wants to be a professional golfer, he will have my support, but what I want for him is to have a solid education."

Ballesteros maintains that he is neither a religious man nor one given to meditating about his cruelly reduced capacities. The only times he thinks about life's capriciousness are when he sits down to watch the television news. "Every day I see the unbelievable things that happen to people, and I don't understand why.

"I think, 'Why does it happen to those people'. I think the same thing with myself. Why did it happen to me? It is unfair, because I have been a good person. But it happens to some people and not to others. Why did I win at St Andrews, out of 170 players? Maybe I was lucky. This is my approach to life: some days are good, some are bad. Some people are lucky, some are unlucky."

Ballesteros believes that he is a mixture of both, particularly when he looks back on the extraordinary circumstances in which he was taken ill. "I was in Madrid with Ivan and my son Miguel, to have lunch. After that my plan was to go and visit an exposition in Munich. But all of a sudden I didn't feel good, I felt dizzy.

"Ivan said, 'We have to go to the emergency room very quickly, because you're not looking very well'. So I went, and all I know is that I spent 72 days there. The four operations were unbelievably tough. I didn't expect any of the things that happened to me.

"But the doctors said I was very strong physically and that I had a lot of air in the blood, so I was well prepared for the surgery. In one way, I guess, I was very lucky. The hospital and the doctors were right there. Rather than next to La Paz, it could have happened in Germany. Ivan and myself, we don't speak German."

Ballesteros's struggles mean he is no longer allowed to drive a car or ride a bike. For a man who used to relish competitive cycling, this is a torment. He has, however, little choice, after an incident in March when his golf cart veered off an embankment, throwing him head first on to the ground.

Increasingly his only outlet for exercise is the occasional walk on the beach. That, and some light practice on the nine-hole pitch-and-putt course in his back garden – a loose definition, given that it measures 17 acres. He jokes that he is still "hitting his drives a bit to the left", but that this would be just the right shape of shot to suit St Andrews.

His game, like his predicament today, can seldom be analysed without a feeling of what has been lost. Although he finished his career with three Opens and two Masters green jackets, problems in his lower back caused a sharp deterioration in his game in the Nineties. His form off the tee was so erratic it was a subject of parody.

When Ballesteros reflects on his health, the sunshine briefly lifting his spirits, he reaches automatically for a golf metaphor. "It's like when you start a round, you bogey the first three holes, but there are still 15 left to play. Here I am, more or less, on the 12th hole.

"Coming back from the operations, from what I have, is very difficult. The damage is all from the brain; it's not like an accident where I fell down.

"You know, for everything in life, there is always a beginning and there is always an end. This is the tough part, the most difficult thing, when you see that it's coming: the end."