New Royals ballpark? Kansas Citians have often said ‘yes’ with stadium, arena on ballot

Kansas Citians have been asked a handful of times to support a sports stadium or arena with their tax dollars. And on almost every occasion, at least when the vote came from Jackson County taxpayers, the answer has been “yes.”

Sometimes resoundingly.

Will those winning ways continue with a new baseball stadium looming as the next ask of public money?

Kansas City Royals owner John Sherman says he wants a new ballpark before the Kauffman Stadium lease expires after the 2030 season. Downtown sites have been most often mentioned. Officials in North Kansas City have outlined a plan, too.

If downtown becomes the destination, Sherman has pitched an extension of the three-eighths-cent sales tax in Jackson County, a 25-year plan passed in 2006 to help pay for improvements to Arrowhead and Kauffman stadiums. It passed by a comfortable margin.

The strongest argument at the time: Voters wanted to know with certainty that the Chiefs and Royals would be residing in Kansas City for the next quarter-century. One argument against passage of that measure was the Royals would be better served by a downtown stadium.

But the Royals and then-owner David Glass weren’t as interested in a downtown location as the team is now.

Public support likely would be required in Clay County, as well. The notion of a half-cent sales tax has been floated.

Ambitions for new sports structures endure a series of twists and turns. Every step is scrutinized and second-guessed. From proposed sites to funding methods to target dates for completion, history informs us that no Kansas City stadium or arena project has evolved without complications.

And they’re not guaranteed to pass. Johnson County could’ve been home to teams in the NHL and Major League Soccer. Both times, the measures met resounding defeats at the ballot box.

But when Kansas Citians have been asked to support a new stadium or improvements to an existing one, they’ve often done so. Here’s some history:

2006: YES TO STADIUM IMPROVEMENT, NO TO ROOF

On April 5, 2006, Jackson County voters approved a three-eighths-cent sales tax for improvements for both stadiums.

Of the $575 million package, $450 million came from this tax. The Chiefs kicked in $100 million and the Royals $25 million.

At Kauffman Stadium, passage of the sales tax produced wider concourses, the Royals Hall of Fame in left field, the sports bar/restaurant in right field, a new Crown Vision video board and other improvements. At Arrowhead Stadium, the Chiefs built a new Hall of Honor and added more luxury seating as part of their renovations.

Arrowhead (now known as GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium) opened in 1972; Kaufman opened as Royals Stadium in 1973. Both were showing their age, and voters agreed that some upgrades were needed.

“There was a belief the Truman Sports Complex was worth preserving and extending as a home for the Chiefs and the Royals,” said Jack Holland, then a financial adviser to the Jackson County Sports Authority.

The final tally:

Yes votes: 78,773 (53.5%)

No votes: 68,517 (46.5%)

What the Truman Sports Complex didn’t get was a roof.

A separate measure on the ballot asked Jackson County taxpayers to support a use tax on goods purchased outside the state. The idea was to raise $170 million of the $210 million needed to pay for a rolling roof that could be used to cover both stadiums. Put a cover over Arrowhead and Kansas City might have become a host site for a Super Bowl, Final Four and other championships.

“I’m surprised,” Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt said at the time, after the votes were counted, “because I frankly thought there was a chance that the roof would pass and not (improvements).”

The rolling roof vote:

No votes: 75,313 (51.3%)

Yes votes: 71,394 (48.7%)

2006: SOCCER COMPLEX IN JOCO A NO-GO

Johnson County residents went to the voting booth to decide the fate of a proposed new soccer stadium for the Kansas City Wizards, who had played before small crowds at Arrowhead Stadium since joining Major League Soccer as a charter member in 1996.

The stadium would be part of a larger complex, including 24 field for youth soccer, at Highway 69 and 159th Street in Overland Park. The Wizards’ ownership group wanted taxpayers to approve $75 million in county-issued bonds, supported by a property tax increase.

On Nov. 7, the no-votes won in a landslide:

No: 116,498 (64.2%)

Yes: 64,960 (35.8%)

Those sentiments eventually turned. The former Bannister Mall location in Southeast Kansas City became an option in the form of a $950 million redevelopment plan for the region. But the financial crisis of 2008-09 stalled the progress, and Kansas swooped in with tax credits and cash incentives for the $200 million stadium at Village West.

The Kansas City Current of the National Women’s Soccer League are scheduled to open a new $117 million downtown stadium in time for the 2024 season. The structure is almost completely privately financed.

2004: YES TO TOURNEY-SAVING ARENA, BUT NO NBA, NHL

Kansas City had been home to a major conference basketball event since 1946, but as Kemper Arena aged and new venues opened in Dallas and Oklahoma City, Big 12 officials decided to move the event. The 2003 Big 12 men’s tournament was the first to be played outside of Kansas City.

Kansas City Mayor Kay Barnes, the daughter of a high school basketball coach, made downtown development with a new arena a priority in her campaign and administration.

The prospect of landing an NBA or NHL team was part of the allure, and the majority of the funding (57% of the $250 million arena) would come from taxes on hotels and car rentals.

“And not general taxpayers,” Holland said. “That, and the fact we were at risk of losing the Big 12, which has a deep history here, drove the campaign.”

Also key in that campaign: St. Louis-based Enterprise Rent-A-Car emerged as a force in opposition to the tax. We’re going to let St. Louis prevent us from building a new arena?

The vote from Jackson County:

Yes: 66,821 (57.5%)

No: 49,484 (42.5%)

1972: JOHNSON COUNTY ICES HOCKEY ARENA

In 1971, with construction underway for the Truman Sports Complex, Kansas City found itself in position to land an NHL franchise.

Build a new arena and KC would be considered a front-runner for NHL expansion and NBA relocation.

Thus began two wild years of starts and stops. Then-Star sports editor and columnist Joe McGuff calculated four potential ownership groups, 10 arena proposals and seven possible sites for a new arena. This period also included a big defeat in the polls, but not by Jackson County voters.

The NHL awarded franchise rights to Johnson County, Kansas, where an 18,000-seat arena would’ve been built at Switzer and College boulevards. So a proposed 1- to 3-cent sales tax on restaurants and hotels within five miles of the building was put to a vote.

And JoCo said no thanks:

No: 54,084 (61.6%)

Yes: 33,713 (38.4%)

The vote carried in just two of 165 precincts. But Kansas City didn’t lose the rights to a new NHL team. An arena site in the West Bottoms won out. The financing plan included $10 million from revenue bonds in conjunction with the Jackson County Sports Authority, $5.6 million from general revenue bonds and contributions from the R. Crosby Kemper estate totaling $3.2 million. Final price tag for the new arena: $22,939,058.

So Kemper Arena opened in 1974 and was home to the NHL’s KC Scouts for two years and NBA’s KC Kings for 13 (the Kings spent their first two years in Municipal Auditorium while Kemper was being built and three total years sharing home dates with Omaha).

Today, Kemper is known as Hy-Vee Arena and has been repurposed as a youth sports and community gymnasium facility.

1967: YES TO TRUMAN COMPLEX, CHIEFS AND ROYALS

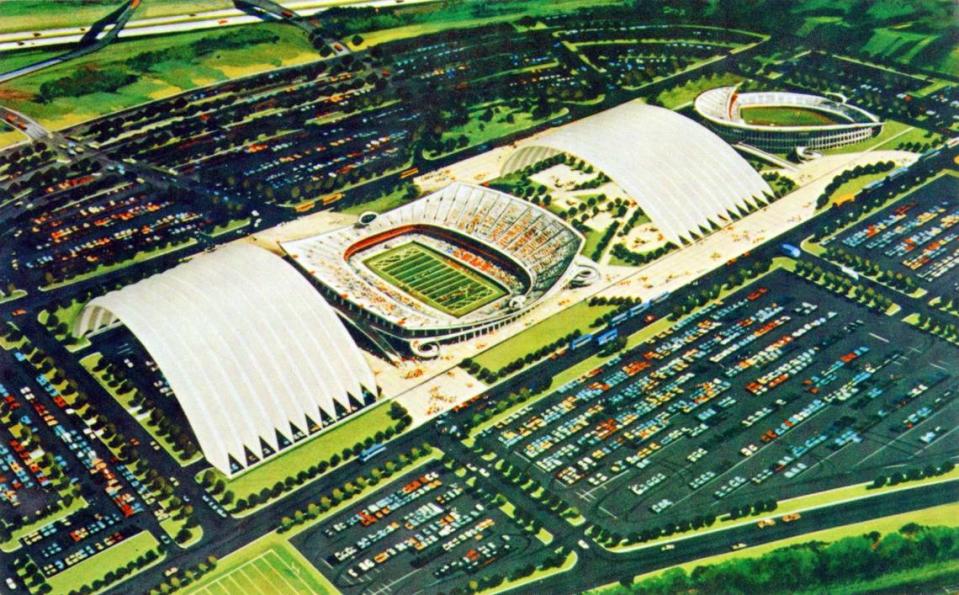

Other cities were building cookie-cutter multi-purpose stadiums, and Kansas City toyed with designs for a domed arena to replace Municipal Stadium. A basketball/hockey venue would be constructed on the same property.

Eighteen sites were initially considered for the new sports structures, but it came down to two. Cheaper land gave the Leeds neighborhood near the intersection of I-70 and I-435 the edge over the central business district south of Municipal Auditorium.

Based on the suggestion of Denver-based designer Charles Deaton, Kansas City went against the grain of the times and unveiled plans for sport-specific adjacent stadiums that would share a parking lot.

A new ballpark was planned to keep the Kansas City Athletics in town, but owner Charley Finley had been looking to relocate for years. The A’s would soon move on to Oakland, Calif., so the proposed baseball stadium would be used for a potential Major League Baseball expansion team.

As for the Chiefs, they were coming off an AFL championship and an appearance in the first Super Bowl. They loved the idea of having their own stadium — they’d been second-class citizens to the A’s in their early KC years after relocating from Dallas. When it came time to campaign for the $102 million bond program, which was divided into seven separate ballot issues, Chiefs stars like Len Dawson and Buck Buchanan made several appearances.

Two-thirds approval was needed to secure the $43 million initial investment for the stadiums, and although early polling suggested the effort would fall short, the final results spelled victory:

Yes: 61,872 (68.9%)

No: 27,878 (31.2%)

A rolling roof was part of the plan, but that aspect was scrapped because of cost overruns and delays caused by a labor strike.

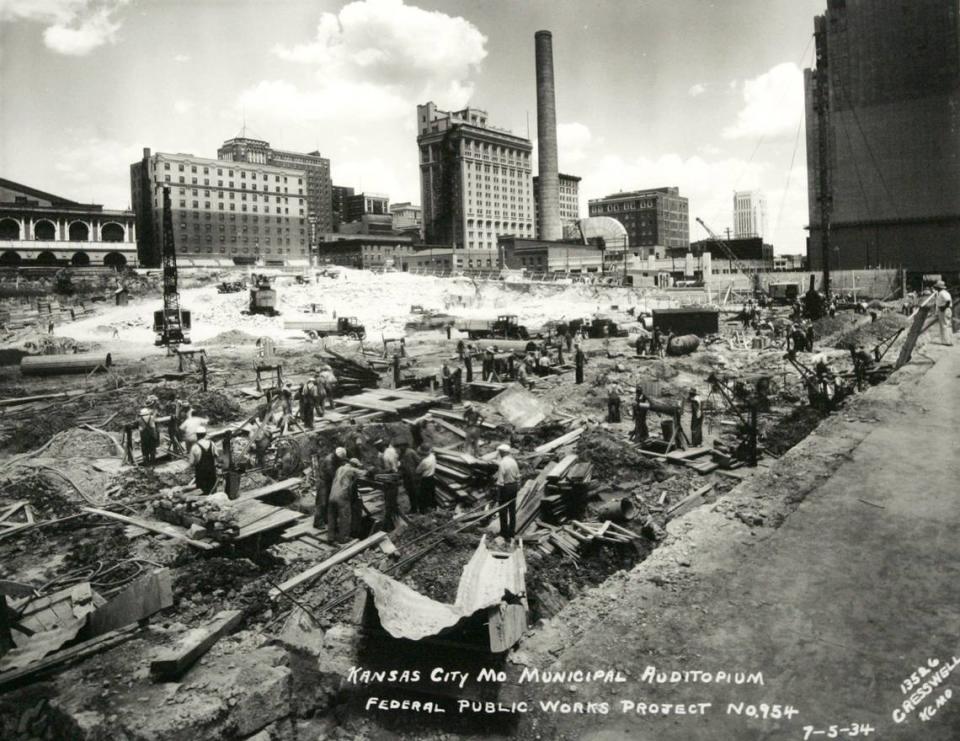

1931: YES TO MUNICIPAL AUDITORIUM, KC’s ‘GREATEST DAY’

In 1931, in the midst of the Great Depression, Kansas Citians were so enthusiastic about a new arena that they voted overwhelmingly to approve all 16 projects on a 10-year plan that included an auditorium and stadium.

Nearly 90,000 went to the polls for the election of May 26, 1931. Each project, including a new city hall, a Jackson County courthouse and an airport expansion, needed a two-thirds majority to pass. And pass they all did, with the auditorium approved by the widest margin: 80%.

Kansas City was beside itself. The headline on the front page of the Kansas City Times the day after the election read, “Yesterday was Kansas City’s day — perhaps the greatest day in its history. Isn’t it bully!”

Initially, $4.5 million of the $40 million bond approval was assigned to the auditorium. The final price tag climbed to $6.5 million.

Interestingly, the building that would host the most NCAA men’s championship games (nine), and in March played host to the 2023 Big 12 women’s tournament, wasn’t built for basketball — or any sport. There was no NBA then, and the NHL played only in the Northeast and Canada. Municipal Auditorium opened in 1935 for musical performances.

Plans called for the building to seat 13,000-17,000, but it wound up around 10,000.

“Even before the sports, the basketball hadn’t started, Kansas Citians loved the building,” said Mick Lehner, whose uncle, George Goldman, was Municipal’s first director. “I think because it was so unique ... Kansas Citians loved the newness of it and the fact that it was so exceptionally designed.”

The first basketball game between college teams at “Muni” didn’t involve Kansas, Missouri or Kansas State. On Dec. 22, 1936, Central Missouri — then known as Warrensburg Teachers College — played a Stanford University squad led by All-America Hank Luisetti.

Eventually, in 1972, the NBA arrived when the Kings relocated from Cincinnati to Kansas City/Omaha.

An interesting aside to the 10-year plan: Also approved was a sports stadium that could seat up to 80,000. It was eventually scrapped.