Remote drug testing? Here's how USADA's new procedure works for UFC athletes

In the early days of the anti-doping movement, when it wasn’t particularly difficult to buy clean urine and when devices such as “The Whizzinator” were a thing, it became obvious that if an effective test was going to be administered, a doping control officer would have to personally observe the subject providing the urine sample.

That meant the doping control officer had to go into the bathroom with the athlete, watching him or her and certifying that the urine collected was from that athlete and not from a device the athlete may have hidden somewhere on their person or in the bathroom.

But technology has come to anti-doping, and in a big way.

On Friday, I took part in a remote anti-doping test administered via Zoom by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), and it was similar to ones that five UFC athletes are taking as USADA adjusts to the coronavirus pandemic.

It was a surprisingly easy and simple process that clearly would take less time in future tests because I wouldn’t need every detail minutely explained to me like Kris Forberg, my doping officer, patiently did. Five UFC athletes — Felicia Spencer, Ashley Yoder, Jimmy Rivera, Eryk Anders and Cory Sandhagen — are participating in the trial.

With people required to work from home during the pandemic and the need to socially distance, USADA accelerated the development of this new procedure in partnership with the UFC that allows testing officers to stay home.

With roughly 600 athletes on the roster at any given time, USADA doping control officers usually travel the world to test UFC athletes. That’s a huge expense, and cost has been cited by many other combat sports promoters as a reason for not following the UFC’s lead and adopting 24-7-365 testing.

But by allowing the doping officer to stay at home and not come to my house, both of us were safer.

“There’s no stone we’re going to leave unturned and we’ll do whatever we can to try to make things safer for our athletes,” said Jeff Novitzky, the UFC’s senior vice president of athlete health and performance who works with USADA on the promotion’s anti-doping efforts. “Even in the area of anti-doping, we’re continuing to trail-blaze and setting an example for other MMA promotions and even other sports. We’re proving here that we’ll do anything with good social distance or, in this case, no person-to-person interactions, to be able to continue to test our athletes and make certain they are competing clean.”

USADA CEO Travis Tygart said the agency began this process about 18 months ago prior to the pandemic to make testing less costly in both the Olympics and the UFC.

He also had the goal of making the testing less burdensome on the athletes.

“When we were talking about this idea originally, we’re always looking to advantage technology and make it easier for athletes and make it more convenient and less costly, all of those types of things,” Tygart said. “[COVID-19], obviously, forced us to fast-forward that effort. We were able to roll out in our Olympic program and our UFC program in rapid fashion and the staff was able to do it.”

Sandhagen confirmed that the USADA staff hit one of Tygart’s goals. It is definitely easy for the athletes to do. He said he had no issue with the previous system but gave a big thumbs up to the so-called virtual test.

“I thought it was awesome and I can’t imagine it being any easier,” Sandhagen told Yahoo Sports.

That was my experience, even though on Thursday when I first mentioned to a colleague that I was going to do this, I had my doubts. And he immediately questioned how effective the testing would be and speculated that fighters would soon be able to cheat.

That was the first question I asked Novitzky and Matthew Fedoruk, USADA’s science director. But part of the reason I took the test was so that I could more intimately understand it and see if I noticed holes in the system.

There were a few things that were on my mind after speaking to my colleague about potential flaws in the system: Could I hide urine somewhere in the bathroom? Could I put something into the urine that would break down whatever I had theoretically taken? Could I hide someone in the bathroom who I knew was clean who could urinate for me?

From a scientific standpoint, USADA seems to believe it has all of those bases covered. But more on that in a second. The process itself is fascinating.

USADA’s new remote drug test explained

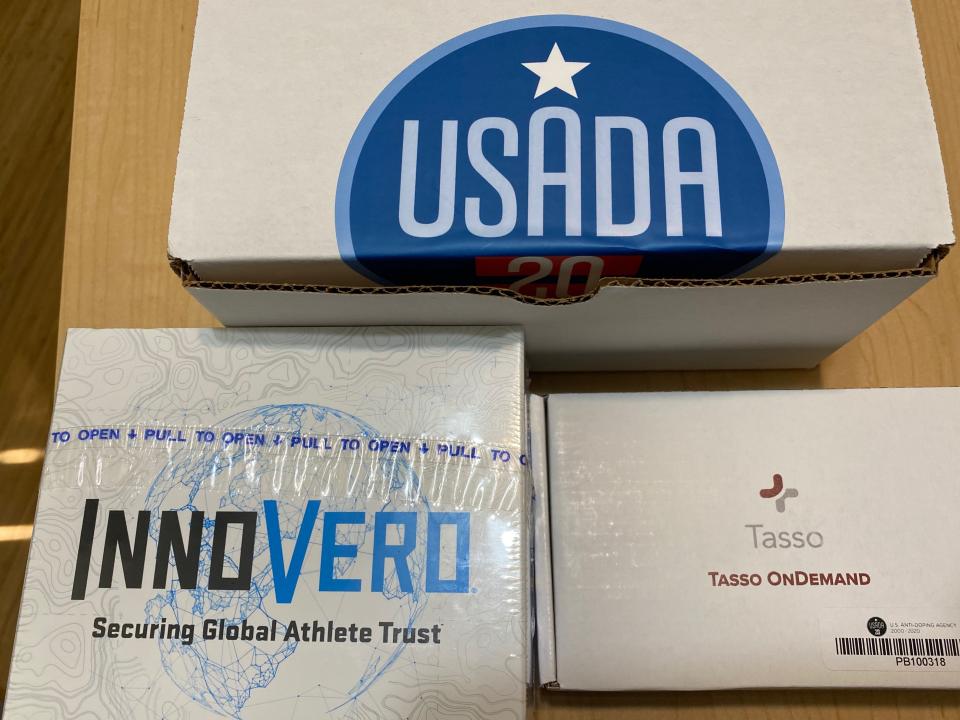

I agreed to be tested late Thursday and on Friday morning, a surprisingly big box was delivered before 10 a.m. by UPS. I was told that I would get a call from a doping control officer, but I wasn’t told when.

I needed to have internet access and some sort of mobile device. Fortunately, I had a mobile phone, a tablet and a laptop.

A little after 11 a.m. Pacific Time, Forberg called me and the testing began. We spoke via Zoom and he was on his laptop and I used my iPad Pro. He took me through the test like he’d done for Sandhagen, Spencer, Yoder, Anders and Rivera. He was incredibly patient and detailed and it was as simple as could be.

I opened the delivered box and took out the items that Forberg told me I’d need. I placed them onto my desk. Then, he asked me to take a specific box with my iPad into the bathroom. I placed the box on my bathroom counter, and then gave him a view of the entire room. Then, I walked through the door into the bathroom while holding the iPad. I gave him a full 360 view of the room so he could see that nothing was hidden in there and that no one else was in there.

He instructed me to put my iPad on the floor facing the door to the toilet. He told me to urinate into a cup that held 180 milliliters and to provide at least 90 milliliters.

When I closed the door facing the toilet, he announced the time, and was the first and only time during the process he couldn’t see me. I filled the cup, finished into the toilet, then went back out to complete the test. There were two bottles and in one, I needed to pour 60 milliliters of urine into it and into the second, 30 milliliters. I also was required to put various stickers with bar codes and numbers on them, and I repeated them to Forberg to make certain everything matched.

I took the temperature of the urine by placing a provided strip on the cup and then poured a couple of droplets onto another strip to see the specific gravity. I was slightly dehydrated. As I was getting ready to use the dropper to put the urine onto the strip, I inadvertently knocked the strip onto the floor. I instinctively reached down to pick it up but Forberg told me he couldn’t see my hands, so I held the iPad while I picked up the strip.

The two tamper-proof cups I poured the urine into turned out to be very highly technical in and of themselves. The kits were developed by USADA and Major League Baseball and produced by InnoVero. In addition, anti-counterfeiting technology is built into the cups so they can’t be manufactured by another party. The cups are also tamper-proof.

Fedoruk said he’s confident that if anyone managed to hide urine in the bathroom without the DCO seeing it, it would turn up on the test.

“We’re trying to replicate the standard [anti-doping test] process as closely as possible,” Fedoruk said. “Having a DCO take an athlete from the point of notification to the sealing of the sample and shipping is our goal. We made some modifications in that process, like you saw, making the athlete show us the bathroom, making sure there is no urine sitting there, making sure there isn’t something to heat the urine and making sure there is no one hiding in the bathroom. Those are modifications we made to try to maintain the integrity of the process.

“Added to that, additional safeguards [were added] like the temperature and then monitoring the sample as part of that overall test history on the athlete through the biological passport and then some of the behind the scenes things we can do like looking at bacterial degradation and [other things] to make certain the sample is that true sample from the athlete.”

Each person’s urine is unique and is shown in the biological passport. If an athlete submits a sample from a person of a different gender, that can be detected, as well as from a dead person (which has happened in anti-doping many times). And if the athlete attempts to put anything into the urine, it will be detected. It was one of the reasons Forberg had me rinse my hands before beginning the process, to clean anything off of my fingers I may have put there to try to cheat the system.

After we finished with the urine collection and packaging, it was time for me to provide a blood sample. I opened a box from a company called Tasso Inc. and took out a small device that looked like a little banjo. Forberg had me wipe my arm with a provided alcohol wipe and then after the alcohol dried, put the Tasso device on my upper left arm. It stuck easily. Forberg then described in detail the process to collect the blood. I’d have to push a red button and it would pinch me and collect a tiny amount of blood.

It took about a minute to get the blood. Because I was slightly dehydrated, it took a bit longer for the blood to fill than normal. Forberg then walked me through the process of packaging that and all of the samples into a UPS bag that would be sent to a lab in Salt Lake City for examination. Three hours later, a UPS driver picked up the packages from my front porch and I texted Forberg to let him know.

The test took less than an hour and I am confident it would have been reduced significantly the next time because I now understood the process.

Added benefits for athletes of USADA’s remote drug test

Spencer said she was comfortable with both collection methods and said she would be confident if an opponent were tested that way that any cheating would be caught. She also said the new cup athletes must urinate into was easier to pour than the old one.

“I felt it went really smoothly and I had no issues with it at all,” said Spencer, who will fight Amanda Nunes on June 6 at UFC 250 for the women’s featherweight title. “It was a good experience. I have hit it off with my doping control officer pretty well, and this time it was virtual, but the remote test went great and I have no problem recommending it.”

It was a simple process and offers the added benefit of helping reduce whereabouts violations. As part of the anti-doping program, athletes must advise USADA of where they plan to be. If they are traveling and forgot to enter it on the app, they can take the test wherever they are if they bring a kit with them. But if they’re not where they say they would be and miss a test, it would be considering a violation, so keeping a kit with them could prevent that.

Novitzky is high on its potential.

“Travis Tygart called me and proposed this idea I think two weeks into the lockdown,” Novitzky said. “The main reason was the pandemic, but what I really, really love about this is it breaks down a lot of financial barriers to anti-doping.

“You’re eliminating virtually all the overhead costs except small shipping fees to get the kits there and sent to the lab. Then you pay a DCO to sit in front of the computer. I love it for us, but I really love it for other promotions, other sports.”

I found the test to be easy, non-intrusive and quick. It clearly could be the way to make quality anti-doping tests more prevalent throughout combat sports, because the costs will be significantly less by not having to have doping control officers fly all over the world.

More from Yahoo Sports: