‘Rape is cheaper than bullets’: The psychology behind sexual violence in war

The reports of sexual violence that have slowly emerged from the events of October 7 defy belief. Gang rape. The mutilation of genitalia. The brutalisation of bloodied bodies.

Some 1,200 people are known to have been killed by Hamas terrorists during the ‘black sabbath’ massacre, but it’s only now that the full horrors of that day are beginning to take form.

Many have been shocked by the accounts of those who witnessed these evils, yet the use of rape and sexual violence in war is not new. Under reported and under prosecuted, it occurs in almost every conflict.

Consider Ukraine. Hundreds of women and some men have suffered sexual violence at the hands of the Russian army. Victims include the elderly, the disabled, even children – none have been spared.

One Russian soldier forced a four-year-old girl to perform oral sex on him whilst her parents watched, according to a UN report published last year. The mother, 22 years old, was raped, and her husband sexually assaulted. They were then forced to have sex with each other in front of the soldiers.

Recent conflicts in Africa have also seen terrible sexual violence. Up to 120,000 women and girls were reportedly raped or sexually abused during the 2020-2022 Tigray war in northern Ethiopia, and this year in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, thousands of women and children are said to have been raped by M23 rebels.

It was not until the Bosnian war of the 1990s that rape was first acknowledged as a weapon of war. Sexual violence was rife in the conflicts that consumed the break-up of Yugoslavia and was investigated by the UN in its International Criminal Tribunal, culminating in the first conviction of mass rape as a war crime.

Yet sexual violence in war is not about sexual desire, say experts, but power. It can happen spontaneously or be used by commanders to meet tactical or even strategic objectives. It’s a form of terror and humiliation that can trigger mass displacements of people and cause trauma that lingers for generations.

Victims include soldiers as well as civilians – prisoners of war are especially vulnerable – while men are also targeted alongside women, with castration and genital mutilation common.

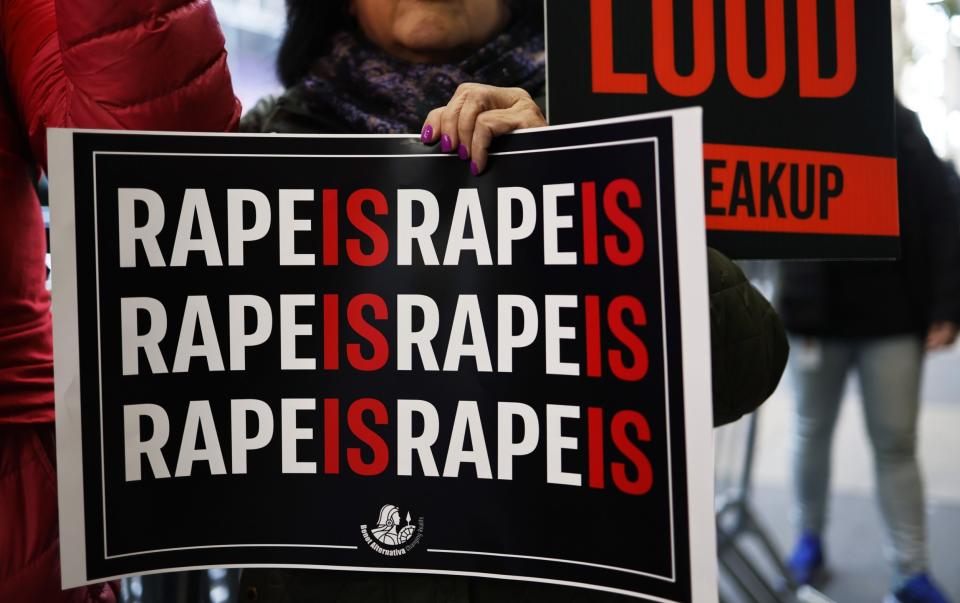

“Rape is cheaper than bullets,” read a 2009 Amnesty International campaign, in reference to how sexual violence can advance the cause of an aggressor or conqueror.

Undermining a sense of safety

In Israel, sexual violence may have been used to instill a “feeling of threat” and fear among the Israeli people at large, and not just the immediate victims of the October 7 attacks, said Dr Sara Merger, an International Relations Professor at the University of Melbourne.

“It speaks to themes of community, solidarity and honour, and it’s very effective at undermining that sense of community safety.”

One eyewitness said they saw a woman being passed from soldier to soldier at the Supernova Festival in Southern Israel. Whilst alive, her breast was sliced from her body and thrown onto the street, the witness said, before she was eventually shot in the head.

Dr Merger suggested there may have been a “strategic objective” to the “horrific events” reported from October 7. These types of atrocities “say ‘Look how powerful my group is, and how vulnerable your group is’,” she added.

Communities as a whole can suffer from the psychological fallout of mass rapes and mutilation, research suggests.

The pervasive fear of sexual assault can disrupt social structures and erode trust among neighbours. The collective trauma experienced by a community can also prolong the process of post-conflict recovery.

Already, there have been reports of psychiatric hospitalisations among the female survivors who witnessed the rapes at the Supernova Festival. Israeli officials believe many will never be able to discuss what they saw that day.

The fallout of sexual violence can also be generational.

Children born to wartime rape often face stigma and discrimination, compounding the psychological burden carried by survivors. These children may grapple with questions of identity and belonging, further exacerbating the long-term impact of such atrocities.

“The experiences of children born of wartime rape can result in a lifetime of detrimental consequences, and the stigmatisation they experience has continued long into the post war periods,” said international development researcher Brigitte Rohwerder, in a report published in 2019 by the UK Government’s former Department for International Development.

During the 1990s in Bosnia, there was an increase in rates of infanticide following the mass rapes of women, with reports of mothers killing their own babies out of shame and trauma.

Many children meanwhile ended up in care due to maternal abandonment. Others were trapped in economically deprived households as a result of the marginalisation their mothers faced from society.

Activists fear a similar story is now unfolding in Tigray.

The Selaam Project, a programme to support survivors of gender-based violence following the war, has collected hundreds of testimonies from victims that show Tigranian women were purposely impregnated to bear Amaha children.

The war was primarily fought between forces allied to the governments of Ethiopia and Eritrea on one side, and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front on the other. Several ethnic groups and militia were involved in the fighting, including Amara forces from the north of Ethiopia.

During the conflict, one young victim of rape was reportedly told “we will replace Mele’s blood [the late Tigran Prime Minister of Ethiopia] with Menelik’s blood [ethnic Amhara monarch]”.

It’s likely that these children whose fathers are known to be enemy fighters will be rejected by their communities, activists believe.

“Children born of rape in war are ostracized,” Dr Merger explained. “This creates lasting generational traumatic effects that are really hard to return from.”

Yet despite its catastrophic impact, rape in conflict mostly goes unpunished.

Underreporting, stigma, a lack of documentation, and a lack of accountability at national and international levels all contribute to the issue, making the prosecution of rape in war extremely difficult.

The pursuit of justice for survivors is made even more difficult for those 72 countries that are not signed up to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), a 1998 treaty which has jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for the most serious of crimes, including rape in war.

Ethiopia is notably not a member of the ICC. This has prevented impartial lawyers from the international community scrutinising reports of sexual violence in the Tigray War, leaving such work in the hands of the Ethiopian government, whose own forces were partly responsible for such crimes.

Yet the ICC’s involvement is no guarantee of success. Ukrainian prosecutors said in January that they had collected enough evidence to open cases into just 153 Russian soldiers with charges of sexual violence – a fraction of the war crimes committed on the battlefield over the past two years.

Advocacy groups and NGOs say that, to better deal with the fallout of wartime sexual violence, improvements must be made to supporting victims of rape and sexual, enabling them to come forward with their experiences. Many want broader international support for the ICC and more countries to sign and ratify the Rome Statute.

A better understanding of sexual violence – in terms of why it’s so widely used in times of conflict and the root causes that perpetuate such brutality – is also required.

“Despite the prevalence of gender-based violence during armed conflict, there is a severe lack of accountability in spheres of criminal justice systems,” said Charlotte Toutai, founder of the Selaam Project. “Action is needed.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security