How preseason tours evolved into money-making, brand-building machines

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — They gathered just as Scousers do at Anfield, hours before kickoff on a Saturday afternoon, to greet their heroes. There were hundreds of them, either side of the entrance, all stationed in wait, yearning for a glimpse. Just a fleeting glimpse, between bus door and stadium tunnel. Maybe a quick wave.

There was no red smoke. But there were railing climbers and piggy-backers and scarves and songs. There was a mass of red-clad humanity pushing air and metal barriers to their respective limits, stragglers sprinting to join it before their chance had gone, all for a moment they had been enchanted by from afar but never experienced. And when the motorcoaches did arrive … when Jurgen Klopp stepped off, and later Mohamed Salah …

And here’s Klopp’s reception at #LFC v Man United pic.twitter.com/olrzINQNiL

— Henry Bushnell (@HenryBushnell) July 28, 2018

Soon they’d join 100,000 others inside, trickling in from overflowing Main St. bars, Interstate-adjacent hotels and tailgates. Hours after that, they were back, lining the entryway again, this time for a sendoff – and perhaps for a selfie or autograph, too. They clamored uncontrollably, the shrill yells of children piercing through the deeper tones of teens and young men. “Sturridge!” squealed a shirtless kid, perched on broad shoulders, upon spotting the English striker. “Danny! I love you so much!”

This, of course, was not Anfield. It was the sixth biggest city in America’s 10th biggest state. But on the last Saturday in July, it nearly doubled in size and became a Mecca. Diehard supporters, soccer connoisseurs and obscure-jersey-wearing partygoers alike had come to see Liverpool and Manchester United. They had come from all across North America, from Texas and Toronto, from Missouri and Manhattan. They spoke in Minnesotan accents and Mexican accents and Merseyside accents. They were fathers and sons and even grandsons, allegiances sometimes split across generations but often shared.

They had planned their vacations around 90 minutes that to many were meaningless. Jose Mourinho even told them to stay home. But they descended upon Michigan Stadium anyway, and in doing so reminded Mourinho’s club why it was here. They were emblems of America’s thirst for soccer. And they’re the driving force behind the evolution of the sport’s preseason: from boot camps and isolation into money-making, brand-building machines.

European skepticism

Fabio Capello didn’t believe in offseasons. Not back in the 1990s, anyway, when he was leading AC Milan to Serie A titles. “For Capello,” Milan legend Paolo Maldini recalls, “vacation is a waste of time.”

Maldini and teammates would report in July for two weeks of grueling training sessions before even taking the field for an initial preseason friendly. Other clubs had their own unique rhythms. Klopp, 14 years before Saturday’s visit to Ann Arbor, took German club Mainz to a remote lake in Sweden where, without electricity or food for five days, the only objective was survival.

Around the turn of the century, however, Europe’s superpowers began to sense opportunity. They recognized untapped potential, especially in Asia and the U.S. And they realized preseason trips abroad could help tap into it.

Their globetrotting desires met resistance. Some managers hated the travel and the occasional logistical gaffes. Others felt high-profile matchups weren’t conducive to preseason development. Players, meanwhile, are paraded around to promotional events with increasing frequency in between sessions.

“In the beginning, we weren’t so happy to come,” Maldini says. “It was difficult. We used to do a long preseason. [The foreign tour] changes everything. After five days, you fly 10 hours and you play against Manchester United. … In the beginning, it was a little bit of a mess.”

But accommodations soon reached luxury levels. Players saw packed American football stadiums, and even opportunities to build their personal brands.

“A new world opened for us,” Maldini says. “The perspective of the players really changed.”

Marketing executives, of course, cherished the exposure as well. The difficulty was maximizing fan engagement without compromising on-field preparations. The difficulty, more pointedly, was needy managers.

And that’s where Charlie Stillitano came in.

Pools, dinner reservations, and appeasement at all costs

To some, he is a disruptor. To others, he’s an oily businessman. But to those who matter – the Real Madrids and Barcelonas of the world – he’s a dear friend and enabler. To Mourinho, he’s “Mr. Zero Mistakes.”

Officially, Charlie Stillitano is the executive chairman of Relevent, which this summer wooed every single one of Europe’s top clubs to its International Champions Cup. Unofficially, he’s as responsible as any other individual for the transformation of preseason. Nowadays, second-tier clubs beg him for ICC invites, offering to play for free, aware of the brand-amplifying power of the sport’s premier friendly circuit. But as Stillitano says over pizza at Giordano’s: “That’s the opposite of what it used to be.”

Back in the day, it was Stillitano doing the begging, going to preposterous lengths to convince skeptical managers and earn their trust. Initially, he had parlayed relationships forged during the 1994 World Cup into others. Build a flawless field for Italy, for example, and famous Italian manager Arrigo Sacchi would say to Sir Alex Ferguson, “Yeah, you can trust these guys,” Stillitano explains. To really win over club soccer’s most powerful men, though, the storytelling New Jerseyan adopted an appease at all costs approach.

Take, for example, Roma’s 2002 visit to the States. Picture Capello outside a bus of peeved players, previously under the impression they were staying in New York City, now refusing to accept a hotel near the Meadowlands. There was no way to immediately rectify the situation. But Stillitano was on the scene. After a discussion that involved Capello feigning fury to mollify his players, Stillitano assured Capello the team would be in NYC the following day.

There are countless stories of limitless accommodation. “You know why we have 11 substitutions in the ICC?” Stillitano begins, launching into one of the many. “We played in Boston, AC Milan against Chelsea. We had seven substitutions. And Jose says, ‘We have to have 11 or I’m not leaving the locker room.’ [Former Milan manager] Carlo [Ancelotti] comes out: ‘I’m not gonna leave the locker room either.’ So I’m in the tunnel with these guys, going, ‘For fuck’s sake, will somebody leave the locker room!?’” There was, of course, only one solution. “So we ended up with 11 substitutions,” Stillitano says with a laugh.

The most common adaptation is training pitch nurture. “We’ve rebuilt the field at UCLA almost every year,” Stillitano says. Last year, he had Real Madrid and Man United squabbling over UCLA’s swimming pool, so he built United an entirely new one. Oh, and he recently got an out-of-nowhere Saturday phone call from Ancelotti asking for a Saturday night reservation worth thousands of dollars at Rao’s, one of New York’s most exclusive restaurants. That type of impossible request isn’t out of the ordinary.

“It’s kinda funny, but it’s to maintain a friendship,” Stillitano says.

And they are now friendships, not solely business relationships. Ferguson frequents Stillitano’s home for meals whenever he’s in the U.S. But the friendships – and therefore the tours – wouldn’t be possible without the faultless hospitality.

“It’s my ninth or 10th time coming to the States as manager,” Manchester City boss Pep Guardiola said on the eve of his 2018 ICC opener. “And every time, it’s perfect.”

Solving nightmarish logistical puzzles

The logistics of perfection are unfathomably complex. Clubs will decide their summer destinations by September or October. But there are often competing interests within a club. There is the football department, beholden to manager and players. There is the commercial department, beholden to sponsors and the bottom line. Sometimes, club presidents get involved.

“Quite often, someone will say, ‘Oh, the president has a friend in Chicago, and he wants you to bring his team to Chicago,’” Stillitano explains. “And the commercial guy will say, ‘I’m not sure we want to go to Chicago.’ And the manager will say, ‘Is there a place to train in Chicago?’

“You’ve gotta somehow please them all.”

Which, of course, is usually unfeasible. It involves endless hands-on negotiation, often directly with the manager. Even then, Stillitano says, “somebody’s always happy and somebody’s always disappointed.”

The crafting of the schedule is a delicate, back-and-forth balancing act between internal interests, Relevent, and commercial and broadcast partners. It often begins with a training base. Some clubs send over grass experts six months in advance to ensure fields are properly manicured.

From there, ICC organizers conceive matchups that will create compelling storylines, and therefore interest and demand. But they’re restricted by America’s vastness and the draining effects of cross-country flights. Clubs complain when their itineraries are the slightest bit sub-optimal. Many schedule drafts are drawn up, then amended or scrapped.

The soccer, in most cases, still takes precedent. “We understand that that’s job No. 1,” says Tom Glick, CCO of City Football Group, which owns Manchester City. “But [the football department] understands that we also come on tour to engage with our fan base, bring in new fans, give back to the community, work with our partners, develop new business. They get that.”

So the Citizens, upon arrival in Chicago on July 17, were incessantly on the move, from sightseeing to kickabouts with local children to a Cubs game.

“We’ve learned how to get a lot done in a very short amount of time,” Glick says. He recalls the club’s first preseason adventure under his watch in 2012 as “a little more chaotic.” Now they’ve established “communication, common sense and ground rules.” They pack in events, bussing players around cities.

A bit more down time might still be desirable. But as Glick says: “This is part of being at a big soccer club. This is what we do.” It’s what they have to do to keep up.

The importance of the preseason tour

Elite European soccer has become an arms race. Under Financial Fair Play, spending power is a function of revenue. Outstripping ludicrously rich rivals requires relentless pursuit of income. The preseason tour, therefore, has become a necessity.

Last decade, according to Stillitano, clubs would say, “‘We’re going to market our brand in the States.’ But I’m not sure they really knew what they meant by that.” They’d say, “If we could make enough money to pay for preseason, that’s great.” Soon, big clubs realized, “Hey, we can make an extra couple hundred thousand dollars. That was big money.”

Now, they need “real money” to compete. That means eight-figure appearance fees from Relevant. But it also means growing their customer base. The up-front payments are increasingly small chunks of annual turnovers pushing $800 million. The value is now the brand-building – the spellbound fans who gathered in Chicago at a Borussia Dortmund kit launch event, who represent future dollars, and a path to continued commercial dominance.

The tours are merely one piece of broader, year-round global strategies. But as Glick explains, there’s no other way to “replicate the immersion you can give to a city like Chicago, New York, Miami, for the business community, the football fans, the local community leaders, the government. … It’s really, really special.”

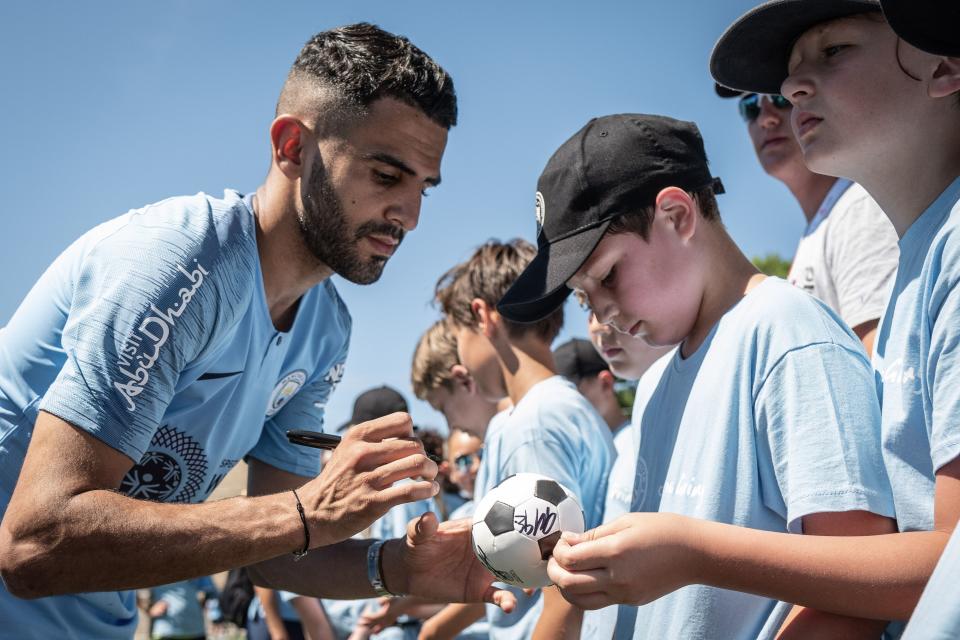

The first-hand access is vital. “It’s important that the players are touchable,” Dortmund COO Carsten Cramer says. “We are a very handsome, touchable, down-to-earth club. If authenticity is one of your core competences, we can’t talk at a distance. So the closeness is important.

“The core business is playing football successfully in Germany and in the Champions League,” he continues. “Because if you’re not successful, you’re not attractive. But this is the cream on the cake. To give the people the opportunity to touch you, to see you, to watch you. You can’t only work by digital assets. You have to be present in the market. So this is part of our [worldwide growth] strategy. It’s not the most important thing. But without [foreign tours], it wouldn’t work.”

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell covers global soccer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.