Peoria basketball book excerpt: The gritty gracefulness of Manual's Howard Nathan

The history of basketball in Peoria is long and illustrious. But one era, in particular, elevated the city's hoops to the national consciousness.

Peoria basketball throughout the 1980s to the 2000s is brought to life in a book from author Jeff Karzen, whose "intense and intimate" perspective leans on dozens of interviews to "chronicle a basketball golden age in America’s quintessential blue collar town."

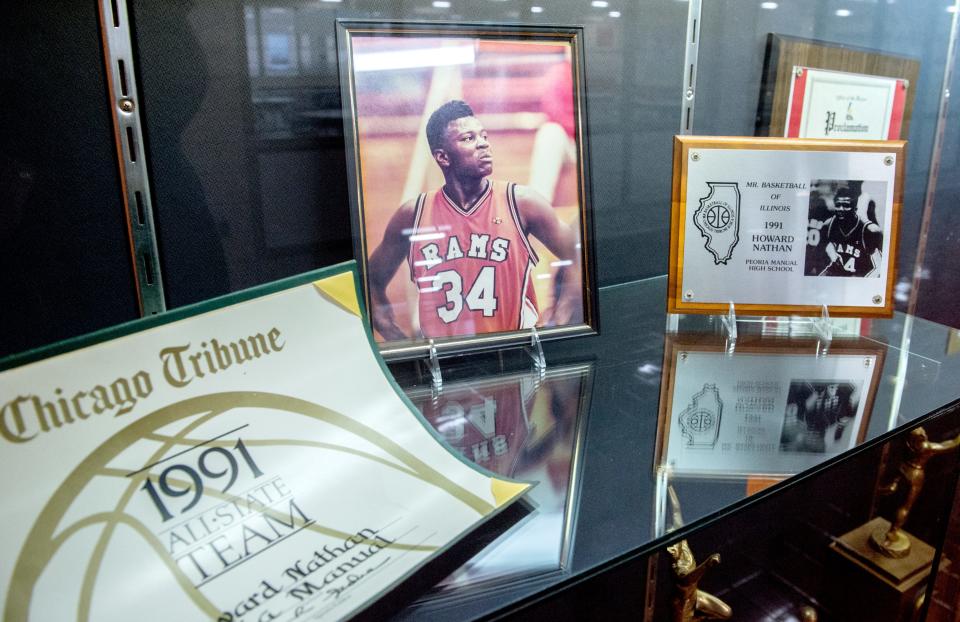

To purchase a copy of “Playgrounds to the Pros", visit press.uillinois.edu. In the following excerpt from his book, Karzen looks at the life and career of Manual alum Howard Nathan, the city’s first Mr. Basketball of Illinois.

The Prince of Peoria

The last steps that basketball hero and former NBA player Howard Nathan would ever take were from the Landmark Bowling Alley to his 1972 Oldsmobile Cutlass. Late at night on July 30, 2006, Howard drove near the intersection of University and MacQueen toward downtown with his younger brother Charles and friend Willie Irby. Ignoring MacQueen Avenue’s stop sign, a drunk 49-year-old Miguel Ceja smashed his van into Nathan’s Cutlass and sent arguably the greatest basketball player in Peoria history and his two companions flying through the summer night.

Nathan’s car eventually landed upside down and slammed into a brick front porch at 2313 N. University St. All the tires had flown off. Car battery too. Willie was ejected from the backseat of the car. Stuck inside the mangled car but conscious, Charles looked at his brother and asked, “Bro, you ok?”

“Yeah, I’m good,” Howard assured him.

The night was pitch black as the Nathan brothers tried to remove themselves from under the destroyed vehicle. Charles, who began the ride in the passenger seat, had no room to squirm out on his side. Looking over at his brother, he spotted a smidge of space to get out from the heaping pile of twisted metal, smoke, debris, dirt, and confusion. Charles tried pushing his brother out from under the car. “My legs are stuck,” Howard said.

Unable to get out, the Nathan boys rested and waited for the paramedics and fire department to arrive. After a few minutes, they started to smell gas from the shattered car.

“I made phone calls to my parents and my sisters letting them know what’s going on and pretty much saying our last goodbyes, because I thought the car was going to explode,” Charles recalls.

When the fire department arrived at the gruesome scene, they used the jaws of life to remove Howard, then 34, and Charles, 29. The three men were rushed to OSF Saint Francis Medical Center. Willie and Charles had sustained broken ribs but managed to escape without further damage. The news appeared much worse for Howard. He had a broken neck and was paralyzed from the waist down.

Doctors may have told Howard Nathan he was never going to walk again, but you wouldn’t have known it from his demeanor in that hospital. Sure, Nathan had a halo around his head as a result of the broken neck. But he was still Junior, the name his family called him. Still Nate the Great. Still the most confident man in the room at all times. And oh yes, that trademark swag and upbeat demeanor was ever-present.

From 2016: Manual coaching staff has championship pedigree

Derrick Booth, perhaps Howard’s closest friend, remembers arriving at the hospital during the early hours of that Sunday morning immediately after the crash to an already packed scene of Nathan’s family and friends.

“This is incredible to think about because this is without social media,” Booth said. “This is not a Facebook post and everybody just arrives. This was the phone chain.”

After some time, a waiting room packed with Nathan’s loved ones was informed that he would be taken out of one room and moved to a different area of the hospital. The group nervously and anxiously crowded into the hallway to see a glimpse of their wounded star. Seizing the moment the way he used to during big situations on the basketball court, Nathan started yelling, “I’m walking out of this hospital! I’m walking out of this hospital!”Booth compared it to Muhammad Ali just before a fight.

“They’re wheeling him down the hall, and he knows this crowd is behind him,” Booth said. “He can’t see anybody. And he’s yelling from a stretcher, ‘I’m gonna walk again! I’m cool! I’m cool!’ And no doubt in my mind that he believed it.”

Tom Kleinschmidt, one of Nathan’s best friends since their high school AAU days, tried to prep himself for the hospital visit. On the three-hour drive south down Interstate 55 from Chicago to Peoria, Kleinschmidt, who was a year removed from an overseas professional basketball career, attempted to envision what it was going to be like seeing his incredibly athletic buddy bedridden.

“I had this speech practiced, and I was going to say all these words of wisdom when I saw him, and I choked when I walked in,” Kleinschmidt said.

“I just asked, ‘How are you doing?’ He looked at me and said, ‘I’m straight. I’m gonna be fine.’ I’m crying and he’s comforting me. He’s on his stomach looking at me and he’s comforting me. I choked.”

Some of Nathan’s friends truly didn’t believe the diagnosis. Junior won’t walk again? Nah, that’s crazy talk. Such was the aura of Howard Nathan Jr. in his beloved hometown. Walking on water might be a stretch, but it’s not ridiculous to say Nathan glided on air in the eyes of Peorians. The thought of him unable to crossover a defender on the court ever again? Unfathom- able. Not our Howard, Peoria reasoned.

![Howard Nathan´s sister Stacey Nathan sheds tears as a photo of the Peoria basketball legend is unveiled Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020 in the Manual High School gymnasium. [MATT DAYHOFF/JOURNAL STAR]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/A77kTcnRKQJUHRDF.gYuhg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYzMg--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/journal-star/5287f0ee5f37c95be0abaa1fd6e8d31a)

• • •

Room 3517 at OSF St. Francis became a revolving door of friends and family as everyone flocked to check on Nathan. Howard was the third of Howard Sr. and Sue Nathan’s seven children. Less than nine years separated the oldest of Howard’s five sisters, Angennette, from Charles, the family’s youngest child. The family is extremely close, and when one of them is ailing, you can be sure the rest are nearby.

About a week after Howard’s accident, an unfamiliar White woman approached the room and said, “I’m trying to find the family of Howard Nathan.” You’re in the right place, the Nathans — who are African American — answered. Visibly nervous, the woman explained that she was the wife of Ceja, the drunk driver who slammed into Howard, Charles, and Irby. Now she was standing a couple feet away from Howard, who was tethered to ahospital bed, unable to move his legs.

The woman explained that her husband couldn’t make it, but they just wanted to say they were so sorry for what he’d done. She said people told her the Nathans were angry and that she should watch her back. The Nathans were stunned. Here they were grieving a traumatic accident and now this? “I said no, that’s not us,” said Angennette. “Whoever told you that . . . they don’t know us.”

Amazingly, Howard held no resentment for Ceja. He was convinced he would walk again. He once told his sister he was glad this happened to him and not someone else, because he was strong enough to deal with it.

“Seriously, that’s who he was,” Charles said. “He forgave people. He didn’t hold grudges. He brought people together. If people were feuding, he tried to figure out a way to get these people together to resolve this matter. That’s who Howard was.”

About a week after his wife’s visit, Howard’s grandfather, Charlie Nathan, Howard Sr., and Sue drove to Ceja’s Peoria house to let him know he was safe and nobody would harm him.

Rams pride: Homegrown leadership for Manual basketball helps youth navigate surroundings

“Howard (Junior) didn’t blame the man,” Sue said. “He told me, ‘Mama, I don’t want to see him go to jail or anything happen to him. He said once upon a time in my life, I was a drunk driver.’ So, he didn’t want nothing to happen to the man. He forgave him. So, if he forgave him, what could we do but tell him we forgave him?”

Angennette has another theory on why her parents took that extraordinary step of visiting a man who had recklessly paralyzed one of their children and injured another.

“My parents had to go and straighten out our last name and who we are as a family,” she said. “We don’t want anybody to think we’re bad people. My dad had to go and take care of that business. As long as my parents had their son and he didn’t die from that car crash, we were OK.”

• • •

Peoria is the kind of basketball town where top players are identified at an early age. Middle school games are events. Years later, fans can easily recall which player went to which middle school. So, when a kid is scoring 40 or 50 points per game — in 24-minute games with no 3-pointers — at Blaine-Sumner Middle School on the south end, word gets around quickly. That’s what Howard Nathan Jr. was doing in the 1980s, becoming a household name in basketball circles by the fifth grade. His name was a familiar one for another reason, too. Howard Sr. had been an excellent player for Peoria Manual back in the early days of legendary Coach Dick Van Scyoc’s run.

Howard Sr. was good enough to play in college, but before that could materialize, Sue became pregnant with Angennette, and Howard Sr. gave up his basketball dreams to stay in town, work, and provide for his young family.

More than two decades later, people were buzzing about the younger Howard Nathan in gyms and playgrounds across Peoria, wondering just how good this powerfully built young guard could be.

“I told people he got his basketball skills from his dad and he got his quickness from me,” Sue said. “When he was born, I went to the hospital at 11 o’clock and at 11:49 he was born. So, he was fast.”

In the fall of 1987, Howard Jr. enrolled at Manual. The Rams had been 31–0 and ranked No. 1 in Class AA the previous year before losing a heartbreaking overtime game to Quincy in the state quarterfinals to end their state championship hopes. Led by star forward David Booth, Derrick’s older brother, and point guard Lynn Collins, the Rams were a verified powerhouse. This was typically no place for a freshman to carve out a role on varsity. Then again, the new kid was no typical freshman.

“He didn’t even touch a freshman uniform, he didn’t touch a sophomore uniform, he didn’t touch a J.V. uniform,” Derrick Booth said of Nathan. “He strictly played varsity. And the games that he didn’t start, he was the first one off the bench. He was that good.”

“So good, so fast, so confident,” said Chris Reynolds, a Peoria Central point guard who later played four years at Indiana. “He had the ‘it.’ Because he was so good, so fast, and so confident and there really wasn’t any flaw in his game.”

In 2018, with his age north of 90 but his mind still remarkably sharp, Coach Van and his daughter published a book titled Manual Labor. A World War II veteran, Van Scyoc tells some terrific stories about a bygone era most people today can hardly believe existed beyond the pages of a history book. He also recounts interesting basketball stories and incorporated excerpts from many players over the years, including Howard Nathan Jr.

Speaking about entering the fray as a freshman, Nathan says in the book, “It wasn’t always smooth sailing and Coach and I would develop a father-son, love-hate relationship; me being a hard-nosed, cocky, wide-eyed teenager and Coach being the ultimate disciplinarian. I should have been more prepared for the discipline because my dad was also a strong disciplinarian. I had the same love and respect for Coach as I did for my dad. I knew he wanted the best for me, and so did Dad. They both told me that where I was going, my friends wouldn’t necessarily be able to go. If I wanted to use my talent and allow it to open avenues of possibilities, I needed to understand that it was for me and me alone. That is hard for a kid to understand.”

The Rams took third place in the state in 1987–88, Nathan’s freshman year. That team was led by seniors Booth, who would star at DePaul, and Collins, who went to Odessa (Texas) Junior College, playing alongside the great Larry Johnson, before matriculating at Arizona State. The two seniors capped their fabulous high school careers with a 29–5 record.

The next two years, Nathan’s sophomore and junior seasons, the Rams went a combined 50–10. During Manual practices, assistant coach Wayne McClain would force the team to make 10 straight free throws at the end of practice to mimic game situations when big free throws must be converted to close out wins. Five kids needed to make two free throws apiece before the team could head to the locker room. One miss and everyone had to run painful suicide sprints up and down the court. It became an unspoken rule that Nathan would take the final two shots.

“He wanted it on his shoulders,” Derrick Booth said. “But he always made them. It got to the point where if it got to Howard, it was game over. We were holding our breath with the first four people. That was our culture, if Howard has it and Howard says we’re cool, we’re cool. We could read Howard and if Howard was confident, we’re cool. And Howard did it day after day in the gym.”

From Playgrounds to the Pros: Legends of Peoria Basketball by Jeff Karzen. Copyright 2023 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

This article originally appeared on Journal Star: Excerpt from Playgrounds to the Pros book about Peoria basketball