Over and out: Electronic communication to call pitches a home run for high school baseball

BELLVILLE — High school baseball has moved into the 21st century.

Over the summer, electronic communication devices were approved to be used between coach and catcher for the 2024 season and so far, it has been so good for Richland County teams using the devices. The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) Baseball Rules Committee approved the changes and the Ohio High School Athletic Association followed suit.

SMILEY KYLEIGH: A light in the world: Kyleigh Reiter's positivity, love for life set to pay off in big ways

"We can communicate directly to the catcher and he can't talk back. It's great," Clear Fork assistant coach Mark Lind, who calls pitches for the Colts, said with a smile. "The intent is to speed up the game and it has worked really well."

The Colts used to use a variety of ways to call pitches. A numbers system was developed where a coach would call out a three-digit number, the catcher would look at a wrist card, find the number and the corresponding pitch and relay that pitch to the pitcher. It was a longer process than it needed to be and one that had the possibility of mistakes made with either mixing up numbers or seeing the wrong pitch on the card. Lind estimated that about 10% of the pitches he called last year ended up with some kind of mistake whether it be the wrong pitch or the wrong location.

"The direct voice communication takes away pretty much every opportunity to make a mistake," Lind said.

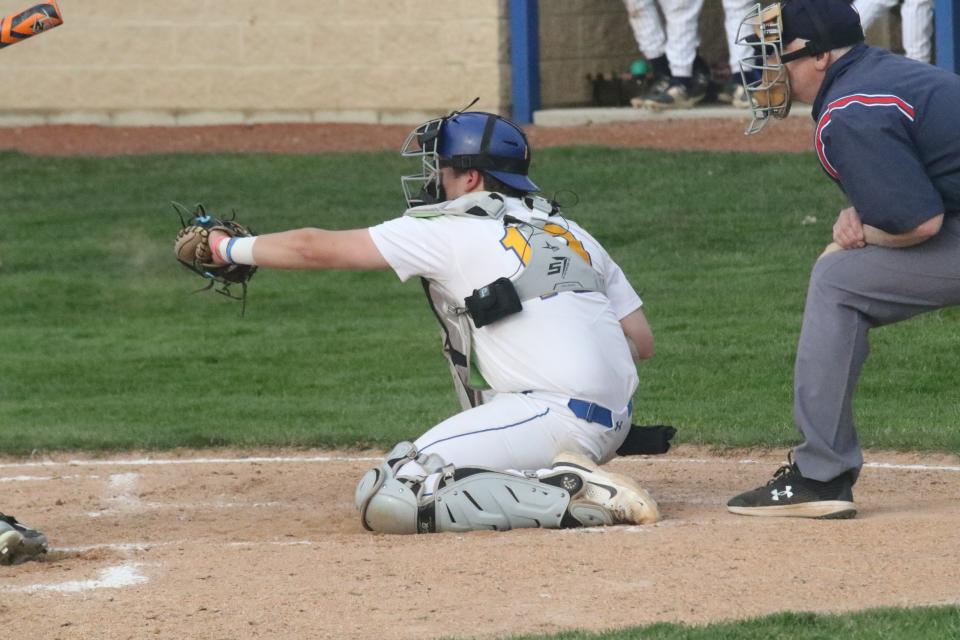

Clear Fork catcher Dawson Staley, who was the starting catcher last season, has noticed a huge shift in the pace of the game with his new ear piece.

"I had a big playbook on my wrist last year and now, I just get direct communication, the game speeds up and there are less likely a chance of having a missed call," Staley said. "I used to get four different signs from four different people for a fastball and now, I just get told right in my ear."

The Colts bought three devices for the 2024 season. One was a Bluetooth device that resembled Apple AirPods and another was one with a direct line into the receiver that traveled up to Staley's ear. And another as a backup. Staley likes the direct line mainly because the wireless pods would fly out of his ear when he threw his mask off looking for the ball.

"Going out and looking like an FBI agent is pretty cool," Staley said with a laugh. "But no, we can go out there and make calls that no one knows and it just helps with our strategy. I didn't really expect that to change the game, but things are much more difficult for our opponents when they don't know what is coming."

Lind had enjoyed the communication freedom he has with his catchers. He is regularly reminding them of defensive situations and bunt coverages that Staley can then communicate to his teammates without it being broadcasted throughout the ballpark for everyone to hear. He also likes the ability to be more detailed with his pitch calls with the exact pitch and the exact placement of the pitch.

"Before, it was hard to get that much information onto a wrist card," Lind said. "We can call pitch plus pitch location or we can tell them to give a sign to shake off. Shake, shake, fastball outside corner at the knees."

And the language is that straight forward. No complicated number system, no message Staley has to decode just to call a fastball down the middle. Fastball, in. Fastball, out. Fastball, up. Simple as it gets.

"I don't have to depend on Coach (Jon) Amicone messing up the signs," Shelby catcher Tanner Hartz said with a laugh. "All he has to do is talk to me, but he just doesn't know how to turn it off. He barks in my ear all the time, but it is so nice to have this because you know what pitch he wants to call and there is no confusion.

"It is so easy. He tells me what pitch and where to set up. Simple as that. I get what he wants, I tell the pitcher where to throw it and it is so much simpler than what it was in the past."

The Whippets used to have a complex system of their own to call pitches which involved four different posters with different pitchers or logos on them and Amicone would use a tap system where he would indicate what pitch he wanted by tapping different places on his face which would then direct his catcher to one of the posters and a certain image which would indicate which pitch he wanted.

"It was complex and now, with the pitch comms, we just tell our catcher straight forward and it helps with our pace of play," Amicone said. "We want our pitchers to work quickly and find that groove. We time our innings and we have a goal we want to meet defensively. Being able to communicate our pitches quickly and efficiently allows our pitchers to get the ball and go and keeps our defense on its toes."

For Ontario coach Mike Ellis, it allows him to communicate his thoughts with his catcher, Jake Chapman.

"We had a hitter go opposite field on us twice so I was able to communicate how we were going to approach him and why," Ellis said. "We stayed inside and we were going to live in there and we ended up getting him out. So just making sure there is that understanding is a huge luxury."

Ontario used to use the numbers system as well. Ellis, who was previously the pitching coach before taking over the head coaching job, would stand at the edge of the dugout, relay three numbers with his fingers to his catcher who would find the pitch on a wrist band and relay that to his pitcher.

"It took way too long and sometimes, it got our pitchers out of a groove," Chapman said. "So now, they can work fast, find that groove and work efficiently."

But more than just calling the pitches, the electronic communication helps in other areas. Chapman likes that his coach can be an extra set of eyes on the field letting him know if a runner is getting too big of a lead or where he has to go with the ball if there is a bunt laid down.

Lind likes to have that ability, too, as well as relaying a message he wants his pitcher to know without having to use a precious mound visit.

"On the defensive side, we are able to tell our catchers to call time and get on the same page with everyone else in terms of coverage," Lind said. "We no longer have to make a mound visit to make sure everyone knows the situation. We can save those visits for more important things."

The pitch comms could allow coaches to relay messages during a team-only visit on the mound without having to go out there himself if they need to.

"I haven't done that, but that is something that can be done," Lind said. "I will tell our catcher to go out and get things organized and while he is walking out, I can say, 'curveball' that way he can tell the pitcher and there won't need to be any sign given."

Which also eliminates an opposing team's ability to steal signs. Baseball teams are looking to gain advantages in any way possible. Lind recalled a tournament game against Edison in 2017 when he and the coaching staff identified the coach in the opposing dugout who was calling pitches early in the first inning. After deciphering the signs, the Colts knew every single pitch for the rest of the game. Clear Fork won 10-1 and went on to win the district championship which propelled them to a state semifinal appearance.

The pitch comms makes that nearly impossible.

"We used to use the number system and there was one year a coach was writing every number on the board that I called and by the end of the game, they had it figured out," Ellis said. "So it is pretty much impossible to steal signs at least from a coach calling the pitches."

The electronic communication can also be used to lighten the mood. If a catcher had a passed ball that allows a runner to move into scoring position or makes a silly mistake and is down on himself, a coach can crack a joke or say something to make his catcher laugh and move on from the previous play.

"I can also have fun with him telling him he has some girls out here who are watching him just to lighten the mood a little bit and make him relax," Ellis said with a laugh.

Amicone will do that, too, but he also finds himself forgetting to mute it when a ball is put in play and he is yelling out instructions or congratulation's on a big play causing Hartz a bit of a headache.

"Besides trying to make my catcher laugh from time to time," Amicone said smiling. "I do feel bad about screaming in his ear. But I didn't expect to see how quickly we get games rolling and how smoothly getting rid of all of the signs and things made the games go."

So far, the electronic communication between catcher and coach has been a wild success and something that has been a major positive for high school baseball, even if it leads to a few busted ear drums from time to time.

jfurr@gannett.com

740-244-9934

X: @JakeFurr11

This article originally appeared on Mansfield News Journal: High School Baseball approved to use electronic communication between coach and catcher