NLDS Game 3: Steady Freddie Freeman the right man to guide Braves back from disaster

ATLANTA – The ball sailed straight from Freddie Freeman’s bat into the Chop House, the premium table-seating hangout bar in SunTrust Park’s right field, so quickly and so definitively that the Dodgers’ Yasiel Puig didn’t even move, but just watched it sail on overhead like a plane already long into its flight.

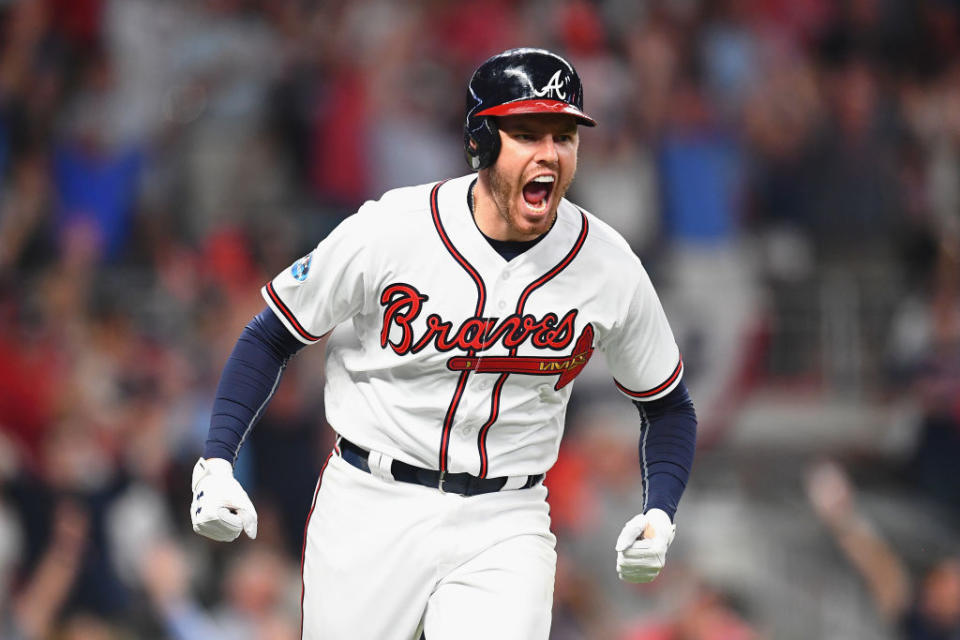

And as Freeman jogged down the first-base line, fireworks accompanying every step of his first-ever postseason home run, the spiritual leader of the Atlanta Braves just looked into the dugout and yelled, a long scream of exultation and relief. The Braves, down 0-2 in the National League Division Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers, had given up every bit of a five-run lead this game, but Freeman was damned if he was going to let this team, his team, go out that way. And so he did what he’s been doing, often alone, for so many years: yanked Atlanta back from the precipice.

“This was the biggest game of our lives,” Freeman told Yahoo Sports. “Seeing the five-run lead go away was not ideal. We held it at 5-5, so we knew we had a chance. That’s what this team’s done all year – when we get down, we come right back.”

“He’s been doing great things for this organization for a long time, and he’s going to continue to do it for a long time,” center fielder Ender Inciarte said. “We’re lucky to have such a great first baseman and someone as clutch as him in that situation.”

Hard truth: Atlanta’s remaining season might be measurable in hours. The Dodgers look stronger in every facet of the game, and Sunday night might have just delayed the inevitable. But thanks to Freeman, the Braves have a touch of hope – and that’s not something this team has been able to say in a long, long time.

When the Braves built SunTrust Park, which opened just last year, the team hedged its bets against a terrible on-field product by creating a wonderland of activities that have very little to do with watching actual baseball. One of the key elements along those lines: an entire curve of the concourse, deep below the grandstands, dedicated to the Braves’ illustrious history. It’s a concentrated history, we grant you, focused primarily on one player (Hank Aaron) and one era (the 1990s), but it’s impressive nonetheless.

You wander that museum, and you’ll see relics from that history enshrined under glass – like the knee brace Sid Bream wore when hobbling around from second to win the 1992 NLCS in one of the greatest defeat-to-victory moments in baseball history, or the bat Hank Aaron used to hit his career-leading home run no. 715 back in 1974.

There are relics you can’t see, as well – the line of Silver Slugger and Gold Glove awards that Braves players must pass every time they walk from the field to the clubhouse, perpetual reminders to the current run of Braves of how high the bar of expectation runs. Sure, most of the current roster – and, at this point, a significant chunk of the fan base – wasn’t even born during the worst-to-first run way back in 1991. But history in Atlanta casts a long shadow, particularly when there hasn’t been much light of late.

The 21st-century Braves have fallen far, far short of their grunge-era brethren’s marks. Before this year, the team hadn’t broken .500 since 2013, haven’t won more than one game in the postseason since 2004, haven’t won a postseason series at all since 2001. You don’t need to tell this year’s team how far they have to go; they’re reminded of it every minute of every day in this ballpark.

Freeman’s only 29, but it seems like he’s been around forever. He’s the last link in a chain that stretches all the way back to the Braves’ glory days, the only player on the team to play a full season alongside Chipper Jones, the last of the Braves’ 1990s icons.

Jones, in fact, threw out the first pitch of Sunday night’s game, racing onto the field to the sounds of “Crazy Train,” his old walk-up music, and for a moment it was like 1995 all over again. Jones, now a happily chill and graying Hall of Famer, threw his pitch to Freeman, a ceremonial toss in more ways than one.

Freeman was on the field when Jones played his final game – a winner-take-all wild card loss to St. Louis best known for its curiously broad interpretation of the infield fly rule – and he’s been holding down first base in Atlanta ever since, calm and quiet and resolute even as his team played like sub-.500 garbage on the field and plunged into scandal off it. Even as the Braves struggled to reach 70 wins, Freeman just kept on delivering,

So it’s not only appropriate he was on the field for Atlanta’s first postseason appearance in half a decade, it’s a bit of Baseball Gods justice that he’s the one who delivered the decisive blow at exactly the moment the team could have folded.

Atlanta hadn’t scored a single run in the first two games of the series, the first time that had happened in all of baseball since 1921. So when Ronald Acuña Jr. created a little baseball history of his own as the youngest player ever to hit a postseason grand slam to put the Braves ahead 5-0, the entire team – indeed, the entire city, could breathe a little easier.

“Ronald getting it going in the second inning was huge for us,” Freeman said. “We just needed to get that two-ton boulder off our shoulders.”

But this is Atlanta, where big leads are only a prelude to bigger defeats. The Dodgers scarfed back all five runs, and suddenly the ghosts of blown World Series, blown Super Bowls, blown national championships loomed heavy and close over Atlanta.

And then came Freeman, facing off in the sixth inning against old teammate Alex Wood, on in relief of Dodgers starter Walker Buehler. Freeman would be the first batter Wood faced.

“Freddie does a good job of keeping things pretty cool,” shortstop Charlie Culberson said. “That’s what makes him a special player. He knows when it’s a big moment.”

On his very first pitch, Wood tried to sneak a knuckle curve past Freeman, and Freeman delivered it to a different zip code. And then came the scream.

“He doesn’t show much emotion, and when he hit it and it went out and he yelled, he got us all fired up,” Culberson said. “Couldn’t happen to a better person.”

“I don’t really know what happened,” Freeman laughed after the game, giving the most buttoned-down description of an exultant moment that you’ll ever hear. “I was pretty excited. It put us ahead, and my emotions took over.”

With the win, the Braves earned another day of baseball, a game that would begin roughly 16 hours after Game 3 ended. So much remained uncertain – for instance, how would the Braves’ already battered, overworked bullpen handle the Dodgers’ relentless, wave-upon-bat-swinging-wave lineup – but for a few hours, at least, those concerns could wait. The Braves were playing meaningful baseball in October again, and making some new October memories that will fit in nicely alongside the classics.

“We didn’t get a lot of hits [Sunday], but we got the right hits,” Freeman said. “Getting a win [in Game 3] was huge. [Monday’s] going to be even bigger.”

____

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Contact him at jay.busbee@yahoo.com or find him on Twitter or on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• MLB postseason predictions: Who we think will win the World Series

• Brewers headed to NLCS after sweep of Rockies

• Mr. October on David Price and what it takes to be successful in the postseason

• Which postseason team needs to win the World Series most?

• Yahoo Sports 2018 All-MLB Team: Mookie Betts, Mike Trout lead way