Memorial Tournament honoree Charlie Sifford paved way for Black instructor Gerry Hammond

DUBLIN, Ohio — Golf instructor Gerry Hammond quickly ran down a who’s who of groundbreaking Black golfers: Pete Brown. Lee Elder. James Black. Calvin Peete.

Then he paused, not for effect but to sigh, because to mention Charlie Sifford is to remember a painful time when whites wanted Blacks to show up at the course only to carry their clubs. Black caddies were OK. Black golfers? Especially Black professional golfers? No thanks.

“But Charlie Sifford is the one who probably had it hardest of them all,” Hammond continued. “He was one of the first to push and break down the barrier and walls, and he received backlash for it.”

What kind of backlash? In 1952, Sifford used an invitation procured by boxer Joe Louis to try to qualify for the Phoenix Open. Arriving at the first green, the 29-year-old from Charlotte found human feces waiting for him in the cup. It would take eight more years before he earned his PGA Tour card, then another 12 months until the tour dropped the “whites only” clause from its by-laws.

Finally, in 1961 Sifford became the first Black to join the same tour that had recently welcomed Jack Nicklaus. Six decades later, Nicklaus’ Memorial Tournament will recognize Sifford posthumously as co-honoree with Ben Crenshaw. Sifford, who died in 2015 at age 92, is the first Black so feted by the Memorial.

“It had to be tough for (Sifford),” said Hammond, who runs the Hammond Golf Academy out of the Golf Depot in Gahanna, Ohio. “Think about it and let’s be real: what if you walked into an all-Black restaurant with your wife and kids? How would you feel?”

Or, to bring things onto Hammond’s professional turf, switch the location from restaurant to driving range.

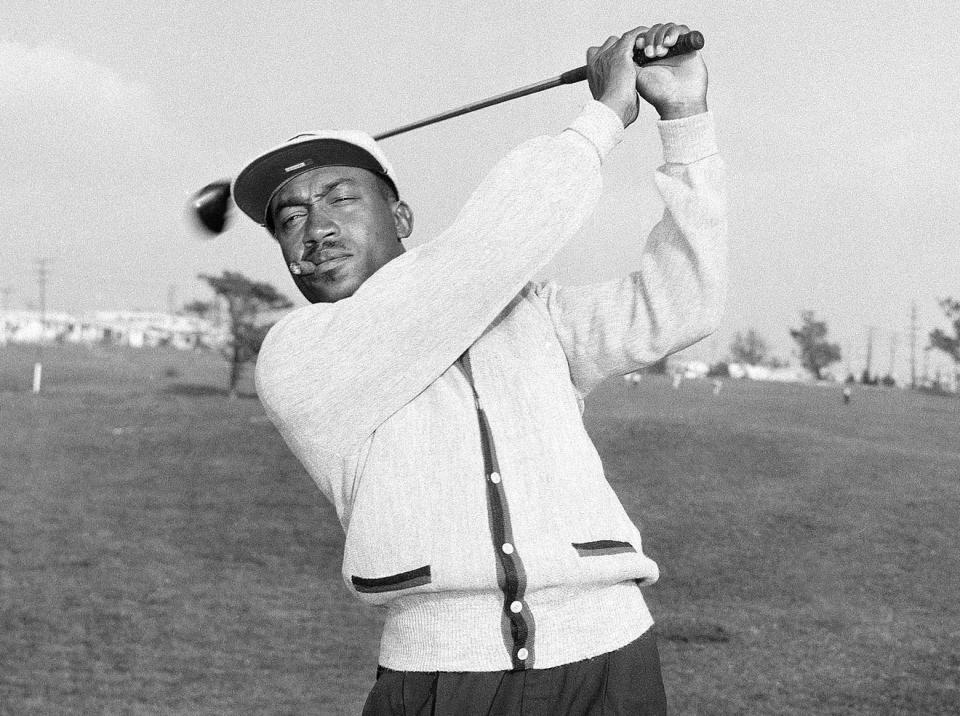

Charlie Sifford in 1957 (Photo: Harold P. Matosian/Associated Press)

Hammond felt the eyes upon him on the practice range during the PGA Championship two weeks ago at Southern Hills in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The 54-year-old attended the major championship as swing coach for Wyatt Worthington II, a 35-year-old teaching pro making his second appearance in the major.

“It’s a really small world when you’re talking about good players and good teachers who are Black,” Hammond said. “Some guys receive you well; with others you can feel ‘What are you doing here?’ There is still some (discomfort) there because you are different.”

It took Sifford winning two tour events, the 1967 Greater Hartford Open and 1969 Los Angeles Open, to finally gain a measure of respect among much of the golfing establishment. In 2004, the Brecksville, Ohio, resident became the first Black inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Tiger Woods, who named his son Charlie in honor of Sifford, in 2015 credited the pioneer with paving the way for his own career.

“I probably wouldn’t be here (without him),” Woods said. “My dad would never have picked up the game. Who knows if the (whites only) clause would still exist or not? But he broke it down.”

Of course, there is always a need for more breaking, whether that means more Blacks inside the ropes or on the business and equipment sides.

Charlie Sifford in 2011. (Photo: Allen J. Schaben, TNS)

“Has it moved? Yes,” Hammond said of racial progress. “Has it moved fast enough? Well, what do we want to see? If you want to see 50-50, we’re not there yet.”

Hammond, who chatted with Sifford at golf events, still sees obstacles standing in the way of young Black golfers making it on tour.

“Any way you slice it, this is an expensive game,” he said. “And there is not really anything happening that is throwing the type of money that I think is warranted to develop high-level players.”

Hammond credited the First Tee program, which introduces youth to golf, as a good starting place, “but these kids need high-level facilities and instruction. They need to be putting on (super fast) greens and fitted for clubs and playing in youth tournaments that require travel, and nobody is throwing out that type of money. That’s where the roadblock is, not necessarily with access.”

Hearing Hammond talk, it becomes even more clear how tough Sifford, who had it; not only did he lack many of the resources described by Hammond, but he also faced lack of access.

“The world we live in has a long way to go as a human race, and golf to me is a part of it, a piece of the whole thing,” Hammond said. “It’s a beautiful sport, because it can connect us in ways other sports won’t. It allows you to spend time with an individual that we never get to engage with for more than 30 minutes. It gives insight into character and personality and shows that maybe this is somebody I can jibe with and do business with. You talk family. It’s a chance to break down barriers.”

An early “breaker,” Sifford was a model for generations to come.

“Just keep plugging away and working and building and playing our part,” Hammond said. “You play your part. I play my part and we keep doing this thing together.”

Well-played, sir.

Editor’s note: Charlie Sifford would’ve turned 100 in 2022. He was born on June 2, 1922, and died Feb. 3, 2015.