The Legend of Mike Trower: Memories, keepsakes abound from a fulfilling career on pit road

Like most collections, the one at the top of Mike Trower’s staircase is personal — curio cabinets, picture frames and shadow boxes all stocked to the edges. “I’m a pack rat of stuff,” he says, adding with understatement that there’s plenty more. “Just little odds and ends.”

Beyond the sentimental value, Trower’s collection is far more than just trinkets and knick-knacks. It’s a personal walk through NASCAR history, with keepsakes marking his remarkable 27-year run of success with some of the most decorated pit crews in the sport. Besides the trophies, fire suits and champagne bottles from repeated trips to Victory Lane, he has the lug nuts to prove it.

“I just got in the habit of, if we won the race, I’d reach down and pick up five or six lug nuts, and I’d send them to my family at home,” Trower says, “and it’s just one thing that I always thought was cool. I just thought … you can’t buy that.”

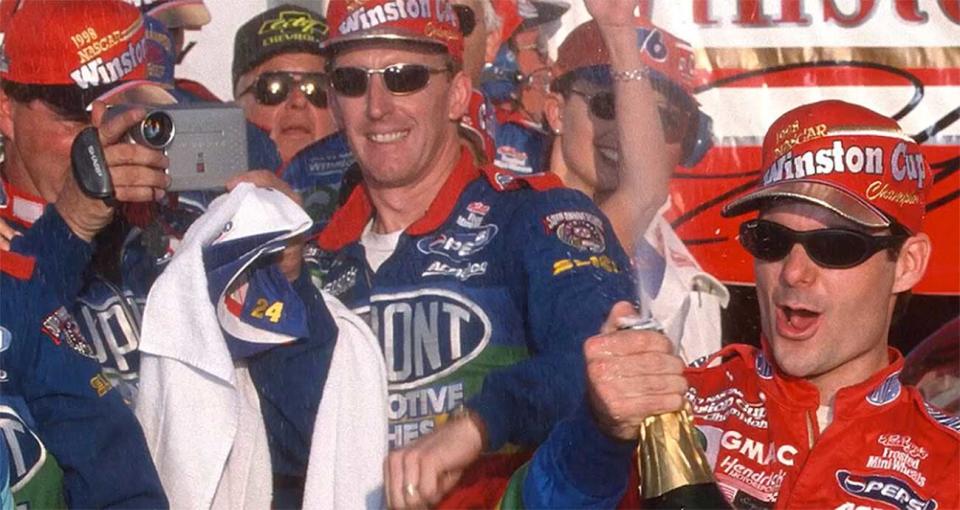

Trower’s name might not come first when reflecting on stock-car stardom, but for those who know, his track record and longevity as one of NASCAR’s top tire changers during a revolutionary era in pit-stop performance have made him a legend. A member of the original Rainbow Warriors crew that helped make the No. 24 Hendrick Motorsports group one of the most proficient teams in racing history, Trower is credited with 73 points-paying Cup Series wins — 49 with Jeff Gordon, nine with Dale Jarrett and 15 with Jimmie Johnson — all drivers who reached the NASCAR Hall of Fame.

RELATED: All of Jeff Gordon’s Cup Series wins | Coca-Cola 600 schedule

That’s a lot of lug nuts — many secured and unfastened personally by Trower — that found their way from pit road to home, marked with driver names, track names and years in fine-point Sharpie, and stored in cabinets, a tall glass jar and multiple shoeboxes. It’s a stacked list: Five Cup Series championships, four Daytona 500 wins, the Winston Million, multiple Coca-Cola 600 wins, the first Brickyard 400. When those three drivers made pit stops on the way to all of those crown-jewel victories, Trower was part of a select group of over-the-wall elite making sure that the pit service happened as efficiently as possible.

“Mike was, in his day, one of the best, if not certainly the best, on pit road,” said Ray Evernham, a Hall of Famer who was the No. 24 Chevrolet crew chief during the Rainbow Warriors era. “Mike was good, he was steady, he was fast and he just didn’t make mistakes. When he came to the 24 car, that immediately set the bar for what everybody else had to do. You had to keep up with Mike. The jack man, the rear-tire guy, the tire handler — Mike was our target.”

Trower’s durable nature and reliable hand with a pit gun made him a fixture at going over the wall well into his 40s. Multiple former colleagues voluntarily likened him to pit road’s Tom Brady; another drew comparisons to Cal Ripken Jr., baseball’s iron man. More remarkably, his quarter-century-plus of pit-stop excellence came as Trower also worked a full-time job with Duke Energy.

Now 59, those years of five lugs on and five lugs off are behind him, but the mementos and the impressions he made are lasting.

“He’s kind of like a Tom Brady, right? He wasn’t always the best athletically, he wasn’t always the most flashy, but he always got the job done,” said Chad Knaus, who changed tires in his early years alongside Trower and is now Hendrick Motorsports’ VP of Competition following his legendary career as a crew chief. “He just always used his resources, used the people around him, he was always very physically fit, and just worked at it. That’s just it. He was a worker, and he worked hard to make sure that he stayed in tune as the car has changed, the technique changed, the wheels and the equipment and all of that. He just stayed engaged.”

• • •

Mike Trower grew up in New Hampton, Iowa, and his exposure to racing came early. He attended his first Cup Series race at Michigan International Speedway as a fifth-grader in the mid-1970s, and witnessed his first Daytona 500 in 1977 (he’s been to 47 more in the years since). By his middle school years, he was already helping his father, Dave, with the race cars that he campaigned at local area tracks.

An advertisement for a pit crew school near the 1-mile Rockingham track brought him to North Carolina shortly after his high school graduation. When the training course was abruptly canceled, Trower stuck with the move, going to a two-year tech school the next town over. He began his full-time job in 1984 with Duke Energy — then known as Duke Power — charting a path with an engineering role in distribution, a career he holds to this day.

Trower’s journey in big-league racing began with independent driver/owner Dave Marcis, first wielding the fuel catch-can before eventually graduating to changing tires. His first Daytona 500 as a pit crew member came in 1986, and he recalled asking if the team needed help the next week at Richmond. After Marcis asked his crew chief how he’d done, the answer was yes. “So I started and I went to every race after that,” he said.

Pictures of his earliest days with Marcis’ team show how primitive the uniforms were by today’s standards — a short-sleeved shirt with the orange Helen Rae Special colors, maybe a ballcap instead of a helmet, pants with polyester, sneakers, leather batting gloves and volleyball knee pads: “They were as thin as thin could be.”

Though he savored his time with Marcis’ No. 71 team, Trower was looking for a change once the 1992 season rolled around. He had bought a house, was starting a family, and the demands of road-tripping to races on the weekend while holding down full-time employment elsewhere had become difficult to manage. He looked for the right fit on a team that flew to the farther-flung tracks.

Enter Evernham, who had an established connection with Marcis through their time with the International Race of Champions (IROC). Trower had also changed tires on Evernham’s Modified car in a Cup Series preliminary event at North Wilkesboro Speedway.

Evernham was starting a group that would advance pit stops into their next era of progression, building on the foundation that the Richard Childress Racing “Junkyard Dogs” and the legendary Wood Brothers team had established. The just-formed No. 24 team also had a young hotshot named Jeff Gordon behind the wheel, and as crew chief, Evernham needed a professional support staff. The team’s debut came in the 1992 season finale at Atlanta, long regarded as one of NASCAR’s greatest races. Gordon’s debut was a noteworthy component, but it also let Evernham see how Trower and the rest of the crew would react in the spotlight.

CLASSICS: 1992 Hooters 500 at Atlanta

“I think that was really a good test because there were so many people on the 24 team that had really not run or been part of a Cup race, and certainly hadn’t been over the wall in a real event,” Evernham says. “So it was very important for that, and we learned a lot. And the biggest thing we learned is how much we weren’t ready, so thank goodness that Mr. Hendrick let us go ahead and run that race to get prepared for Daytona, because it let us know how far off we were.”

The crew rounded into prime-time form with assistance from Andy Papathanassiou, a former Stanford football player with a master’s degree in organizational behavior, who started just three months before the No. 24 team’s debut as the first pit-crew coach the sport had seen. He was a hands-on player/coach in that first season, manning the jack while Trower changed tires.

Trower’s willingness to learn and his “coachability” were key impressions he made on Papathanassiou, but so was his work ethic — a trait handed down from his father, who worked diligently in his career with John Deere — and his professionalism, which was further shaped by Evernham, Hendrick and the work relationships that followed.

“He was a great athlete, a great thinker,” Papathanassiou says now. “Very good at making adjustments, and I don’t mean adjustments on the car, but adjustments to his own movements. Mike was always willing to give something a shot and work through it till he got it right. How can you do something better? How can you shave off not only time, but how can you add consistency? You can’t just be fast, because if individuals are fast, if they try to do things faster, faster, faster, someone’s going to make a mistake, and that blows up the pit stop and that creates a slow execution.

“Mike always had that mentality, that consistency for an individual and consistency for all the individuals on the team lead to team speed. He always had the right perspective, and then he was always willing. He wasn’t just on the front-tire changer or on the right-front guy and that’s all (he’d) do. Mike was willing to move around.”

Papathanassiou set the standard for the pit-stop practice and workout regimens that would set the team apart, but those drills preceded Hendrick Motorsports’ expansion into building training facilities. The group made do with their surroundings, and Trower remembers carrying wheels, pushing shop rags from one end of the garage floor to the other, piggyback drills, wheelbarrows and lunges. He did this by making a beeline when his Duke Energy duties ended to arrive at the shop around dinnertime. When darkness fell, Trower recalls that the team lit one side of the practice area by opening the shop’s garage doors, then illuminated the other with headlights from their personal vehicles.

“We used to run up and down the hill with people on each other’s backs, for God’s sake,” recalls Shane Parsnow, a tire changer alongside Trower in the 1998 season and who will reach 28 years at Hendrick’s engine department in June. “We didn’t have a full-time gym back then. There was no gym. We would kind of improvise in the fields, just doing drills and crossovers and calisthenics and push-ups and jumping jacks to run and get winded. That’s what we had to work with.”

The method to that makeshift madness paid dividends. The team was already making itself known as a contender but raised more eyebrows in winning the annual pit crew competition at Rockingham in 1994, upstaging the No. 2 Team Penske crew that had won the year before. The Rainbow Warriors lowered the No. 2 team’s record by three seconds, proof that their agility training and videotape study to improve their technique were taking hold.

Other teams began to adapt with their own versions of Evernham’s and Papathanassiou’s system, but the No. 24 team was early to the punch, with Trower as a standard bearer. Knaus recalls the group bonding on the road, packed into a wedge-shaped Chevy Lumina van adorned with sponsor DuPont’s bright colors. At the track, though, the crew was all business.

“He’s a player that anybody would want on their team,” Evernham says. “Mike, I always talk about, is a salt-of-the-earth guy. Mr. Hendrick used to say that to be successful, you’ve got to show up, show up on time, show up with your game face on. Mike and I did hundreds of races together, and he did that every day. I look at him and say that if our team had a team captain, team leader besides Andy Papa at that time, that would have been Mike. Mike set the standard for the other guys. Practice hard, work hard, clean, neat, and just a pleasure to work with.”

For all the wins in the Rainbow Warriors era, Trower says he has a favorite. Gordon was eligible for the seven-figure Winston Million bonus in the 1997 Southern 500, and rugged Darlington Raceway dealt out its traditional four hours of late-summer heat and fury. More than one wall scrape put the No. 24 team in damage-control mode, and multiple adjustments were needed to help the car’s handling.

RELATED: Retro Radioactive: Darlington, 1997

“I jokingly say it, but I felt like my face was melting off,” Trower says. “You stick half of your body under there, trying to reach around red-hot brake rotors and trying to put a full spring rubber in and making sure everything’s right.” Gordon fought back and outdueled both Jeff Burton and Dale Jarrett in the closing laps, aided by the Rainbow Warriors winning the race off pit road on the team’s last two stops.

“I remember jumping over the wall. My wife was there. My son was there,” Trower recalls. “It was just like, right after the race, that excitement, everything, and I almost felt like I was going to pass out. It just felt like you went way high, and then it was like, it’s almost like the blood just coming out of your head, and you had to just sit down. It was like, holy smokes, and that was the most incredible race.”

• • •

As with most sports powerhouses, the time of the Rainbow Warriors’ dominance eventually came to an end. Evernham left the team during the 1999 season to help spearhead Dodge’s return to NASCAR. Less than three weeks after that mid-October announcement, Robert Yates Racing — flush with budget and resources — hired away the entire No. 24 crew, Trower included, to pit Jarrett’s championship-winning No. 88 Ford.

The transaction was monumental. Pit-crew movement was commonplace in those days, but rarely did it make headlines. And many of those deals that came before it were brokered with informal agreements rather than signed contracts.

“It was a group that had stayed together for those six years from ’93 through ’99, and like so many championship groups, dynasties, whatever you want to call it, there were now next chapters, next steps that were starting to be developed,” Papathanassiou says. “Ray and Dodge was one. That crew had a lot of attention and gained a lot of recognition over the years with such great work. It was a highly sought-after bunch, so sure, it was difficult.”

Hendrick expressed his disappointment publicly, and the organization moved forward with Papathanassiou implementing the next stage in his industry-changing strategy with a pit crew development program. Trower & Co. — now dressed in Ford Quality Care’s red, white and blue gear — won in their first race out, with Jarrett at the Daytona 500 in 2000.

“When you feel like you’re good as a group together, and you feel like we’re stronger as a group together than we are individually, we wanted to keep that,” Trower says. “That move was another step in that elevation of the importance of pit crew.”

CLASSICS: 2000 Daytona 500

Any initial resentment wouldn’t last. After four years working at what he called a “super-special place” at Yates, the tougher work-to-shop-to-home commute had taken a toll. He shifted to work for two years with the former MB2 Motorsports team and driver Scott Riggs. While there, Trower’s pit-stop work caught the eye of former colleague Knaus — who had ascended to a crew chief role on the No. 48 Chevrolet for Jimmie Johnson — when the two teams pitted in neighboring stalls during an event at Dover.

Those conversations set in motion Trower’s return to Hendrick Motorsports just as Johnson was beginning his title-winning ways.

“He picked up, but it wasn’t the same,” Papathanassiou says. “He came back not only as a crew member on the team, but also as an example, as a leader, as a veteran for what we wanted to shape that team into. He was the one that had been there, done it. He could talk from a level of not only being able to do it right then and there, right in front of you, but from the experiences we had on the 24 car with Jeff Gordon in the Rainbow Warrior days. Mike brought all of that to the table when he returned with the 48.”

Championships, multiple race wins and many more lug nuts came home with Trower, who began to wind down in his third decade of over-the-wall service. “It was just time,” he says in reflection, and he kept at it with stints with the Wood Brothers, JR Motorsports and finally with Tommy Baldwin Racing in his later years.

“Nobody wants to admit it,” Trower says, “but as a pit-crew guy, you get a little age, you start to lose a little bit, a little step or whatever and you’re probably not going to be on that top-tier team maybe again. But that didn’t deflate anything I did about enjoying pitting a race car, and that fun with just hanging around with the guys.”

Even after his final pit stop at the end of the 2013 season, he remained close with the Hendrick organization as a consultant, helping with coaching and observing the No. 48’s pit-crew personnel. In 2016, he was given his last championship ring — a large, bejeweled 7X that’s in the center of a five-by-five case in Trower’s upstairs room — to mark Johnson’s history-making season.

“The thing I really liked about Mike is anytime I called him, he was like, ‘Yeah, man. I’m there. Whatever you need,’ ” Knaus says. “As we were having some pit crew struggles on the 48, I called him multiple times to say, ‘Hey, can you just come watch? Can you just come try to help? Can you just give a little bit of guidance?’ And he never once wavered, and that says a lot about his character. And you know what, one thing that’s pretty interesting is when he would speak, everybody would listen, and that just tells you right there how solid he is.”

The markings of that final pit stop are arranged in their own case in Trower’s office. Baldwin gave Trower the air wrench, and his car chief spun the 10 lug nuts off the front two tires, zip-tied them together and gave them to the veteran tire-changer. They’re secured next to his gloves and pads, in the familiar pentagon pattern that he coordinated and repeated thousands of times.

“It’s a mental game as much as it is a physical game,” Parsnow says, calling Trower a Ripken-esque player when he assesses his former teammate. “You can’t let the aspects of the race or the crew chief or the driver yelling, interfere with what you’ve got to do. And he was able to put that out and just focus on his task at hand. He was committed to it. Add all those things up, that’s what made him so good for so long.”

• • •

The NASCAR Hall of Fame elected its 15th class earlier this week. A small gathering of its inductees have experience going over the wall — Knaus, Kirk Shelmerdine, Junior Johnson and Leonard Wood, to name some — but those were celebrated for their larger roles in the sport.

The Hall of Fame has inducted drivers, team owners, executives, crew chiefs, engine builders, mechanics and broadcasters. The time for its first honoree either as a pit crew team or individual feels overdue.

“I used to tell people this story all the time,” Knaus says. “In my office, all those years of me being a crew chief, every week … I would watch the races throughout the course of the week. I would be there working, doing whatever it is and in my office, every time the caution came out, you would stop and watch the pit stops, and that’s what all the fans do, right? It can be droned out, just running, running, running, and as soon as the caution comes out and cars are coming down pit road, everybody’s paying attention. Nobody takes a bathroom break during a pit-stop cycle.

“And I completely agree with you, that I feel like that these guys — and soon-to-be gals because we’re seeing some of them — need to be recognized in that manner, and Mike would be a guy that would and should be considered. If you go all the way back to when he was changing tires for Dave Marcis, right through the championships that he won, and the people that he helped, he would definitely be a candidate.”

MORE: All about the NASCAR Hall of Fame

Recognition has instead come in other forms — in years past with the former Copenhagen/Skoal All Pro Team and the annual pit crew competitions, and currently with the Pit Crew Challenge that’s a component to NASCAR’s All-Star Weekend. But should NASCAR’s Hall come calling, Evernham is among those calling Trower a “first-rounder.”

“As important as the pit crew members have been to the success of every driver that’s in the NASCAR Hall of Fame, every owner, every crew chief,” Evernham says, “behind that is an incredible pit crew, and those guys deserve a spot in the Hall of Fame.”

Trower demurs at the mention of stock-car enshrinement, instead crediting the pit crews who paved the way for the Rainbow Warriors — the Wood Brothers and the RCR “Flying Aces” — and those who followed their path, including the “Killer Bees” that serviced Jack Roush’s No. 17 Fords for Matt Kenseth. In reflecting on his own legacy, Trower remains steadfast with the “team first” mentality that carried him all those years. Hearing his name held up as an example for how things should be done on pit road remains a source of pride.

“I didn’t have the fastest hand speed, I wasn’t the quickest around the car at all, but I tried to be smooth and consistent and repeatable with what I did,” Trower said. “I felt like I had the speed necessary, or I wouldn’t have been able to be part of teams and things that I was. I felt like there were people that, you give it one shot, I’ll probably get beat, but give me a string of them, and I think I can come out on top, because I felt like I could do the things over and over. … I just wanted to be a good teammate and do my part, be accountable for what I do.”

In talking with Trower’s former colleagues, one recurring thing stood out.

Knaus: “He has always been a very, very good tire changer. I would bet that he could get down and do it again today.”

Evernham: “Gosh, I don’t even know how old Mike is right now, but I’ll tell you what: I bet he’d surprise some of these guys on pit road.”

Trower says he’s ready to take Knaus and Evernham up on those bets.

“That’s funny,” he laughs. “You don’t have to talk to Ray or Chad, you could talk to me, and I’d say yeah, I think I could still do it.”

Trower turns 60 in September, old enough to remember when the 20-second barrier for pit stops fell and thinking then that he’d seen it all. The single-lug wheel fastener of the Next Gen car has helped speed up pit-stop times, but that performance threshold is now in the nine-second range and quicker for the highly trained pit crews of today.

Trower still stays active by going to the gym, hitting the exercise bike in his office and working in the yard. When he speaks of his time in the sport, you can tell that the lure of pit road is still strong.

“I’d like to try the one lug-nut thing and see how it is,” Trower says. “In your mind, can you do it as good? You know, probably not. But I don’t think anybody that’s competitive … I don’t consider myself an athlete, but the athletic ability or the skill to do something? Yeah, it’s always hard. You’re never going to say, ‘Nah, I’m done. I could never do that again.’ In the back of your mind or part of the front of your mind, I’d have a hard time if somebody called today and said, ‘You changed five lug nuts for 27 years. We need somebody for the Xfinity race this weekend. We’ve got to have somebody to fill in.’ Oh, yeah, it’d be hard for me to say, ‘Ah, no, I don’t think so.’ In my mind, I’d be saying, yeah.

“I’m not saying I’m going to be full-steam up to par, but yeah, I feel like I can still lay down a competitive pit stop with a little bit of warm-up and a little bit of practice.”

Xfinity and Truck Series teams, the Tom Brady of pit road is waiting for your call. And he can bring his own lug nuts.