Before Larry Finch stayed in Memphis, Bobby ‘Bingo’ Smith had to leave | Giannotto

Bobby “Bingo” Smith was supposed to be the first Black athlete at Memphis State University. There’s even a headline that says so.

“Tigers break color line with signing of Smith,” read the front page of The Commercial Appeal’s sports section on May 29, 1965, and with that six years of anticipation, ever since the Memphis State 8 were the first to integrate campus, seemingly came to an end.

But Smith never did attend Memphis State and the story of why he had to leave the city where he became a basketball legend is also a mostly overlooked part of perhaps the greatest sports story ever told in Memphis.

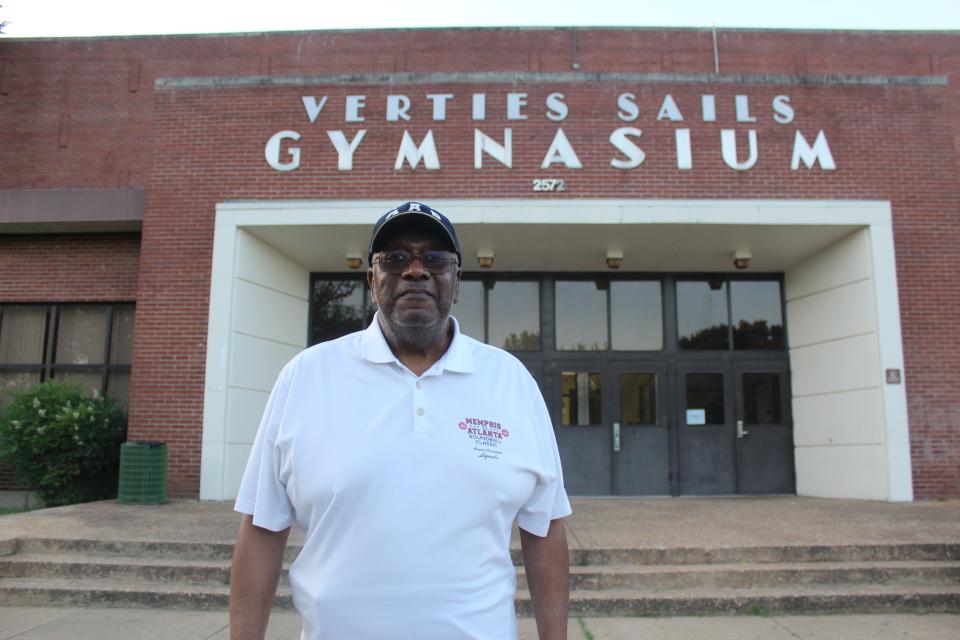

“You might be talking about the greatest athlete to come out of this town,” former Melrose High School coach Verties Sails said, and then he began to recount a moment in time that eventually paved the way for Larry Finch, Ronnie Robinson and even Penny Hardaway to become part of Tiger basketball lore.

'More to it than just a test'

Smith died Thursday at the age of 77. The cause of death was unknown, according to the Associated Press, but he had battled health issues in recent years.

The former Melrose star remains the all-time leading scorer in Memphis area high school basketball history, and second in TSSAA history, with 3,640 points. He was the first Black player to be named to the Associated Press all-state team in Tennessee in 1965. He was also, for a little more than a month that year, the prized signing in former Memphis State coach Dean Ehlers' recruiting class.

Smith chose the Tigers over “125-odd” schools that had approached him, The Commercial Appeal reported, including a courtship by UCLA and coach John Wooden as the Bruins were beginning their run of 10-straight national championships. He had averaged 32 points as a junior at Melrose and 28 points and 25 rebounds per game as a senior.

But the headline read differently on Aug. 18, 1965.

“We’ve lost him,” Ehlers said.

Smith had failed Memphis State’s entrance exam, according to The Commercial Appeal. This sparked controversy and uproar within the Orange Mound community given the racial dynamic at play. It lingered for years.

“The folks at Melrose and then in the community just wouldn’t accept that result,” recalled Sails, who arrived at Melrose in 1966 and coached Finch there. “I was a young guy. I used to play (pick up basketball) at Memphis State. One guy on the team told me this out of his own mouth. He said, ‘Coach, I never took a test.’ That’s true. It’s the truth. He said ‘I never took a test and I’m playing.’ Now, you’ve got the backdrop. Might have been more to it than just a test.”

Smith wound up at Tulsa and his arrival coincided with Memphis State joining the Missouri Valley Conference, which meant annual matchups at Mid-South Coliseum just a few blocks from where Smith was raised.

Smith went 5-0 against the Tigers during his college career, and led two come-from-behind wins during his senior year in 1968-69 when Memphis State didn’t win a single conference game under then-coach Moe Iba.

“They couldn’t get Bobby into school. This is what they were saying. I don’t know how true it was,” said Leonard Draper, the former Memphis Rebounders president who helped recruit Finch and Robinson to Memphis State. “That’s why they didn’t want Larry to sign with Memphis. It led to a lot of bitterness from Melrose because Bingo went out to Tulsa and came back in and beat us.”

“The animosity came because they did not take Bobby Smith,” Sails emphasized, noting that Finch and Smith had the same godmother.

'One of a kind'

But Finch nonetheless chose Memphis State and, as Sails tells it, Smith’s plight convinced Finch he couldn’t go there alone. So Robinson came with him. The two became treasured civic figures, hailed for bringing the Black and white communities in Memphis together under the guise of Tiger basketball in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, especially during the 1972-73 season that ended with a run to the national championship game.

Before them, though, Smith’s exploits created so much buzz in the city, in an era when high school sports here were still segregated, that Melrose and Lester once had a game moved to the old Ellis Auditorium downtown, “so everybody could see,” Sails said.

It was one of the great eras for athletes in the city, with future NBA players like Charles Paulk, Richard Jones and Rick Roberson, in addition to Pro Football Hall of Famer Claude Humphrey. Smith was perhaps the most gifted all-around athlete of the bunch.

Listed at 6-foot-5, he set records in the high jump, had a rocket for an arm on the baseball field and could shoot the ball from just about anywhere on the court, long before there was a 3-point-line. Both Draper and Sails independently told the story of a football game in which Smith caught three touchdowns with a broken wrist.

“The next night, he plays basketball with his left wrist in a cast,” Sails said, “and I can’t remember the number of points but it was an astronomical number.”

“As good a football player as he was a basketball player,” added former Commercial Appeal sports reporter and editor Charles Cavagnaro, who later became the athletic director at Memphis State. “He could have played college baseball and possibly pro baseball, but basketball was his sport.”

Smith was a third-team all-American at Tulsa. It’s also where he picked up his nickname, "Bingo." He was a first-round draft pick by the ABA's San Diego Rockets in 1969 and later became one of seven players in Cleveland Cavaliers history to have his jersey retired.

GIANNOTTO: Penny Hardaway's past is a big part of Mikey Williams' murky future at Memphis

"They don’t talk about him as much now” in Memphis, Draper acknowledged, "but good gracious, he was one of a kind."

It’s one of the quirks of this basketball-mad city, where those who played for the Tigers are remembered and revered far more than those who don’t. It’s how and why Finch and Andre Turner and Elliot Perry and Hardaway have impacted this community in ways both obvious and unseen.

Indeed, while it was decided Smith couldn’t come to Memphis State in 1965, Herb Hilliard also joined the basketball team that season as a walk on. He has been celebrated as the first Black athlete at Memphis State since then, and maybe it’s time to celebrate Smith just the same.

You can reach Commercial Appeal columnist Mark Giannotto via email at mgiannotto@gannett.com and follow him on X: @mgiannotto

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Before Larry Finch stayed in Memphis, Bobby ‘Bingo’ Smith had to leave