The King of Darts

It’s a Friday evening in June in New York City. In a few hours Billy Joel will take the stage in Madison Square Garden. His devotees line up outside. Inside, though, fans are already partying in the Theater at MSG, located in the bowels of the stadium. And they’re not here for the Piano Man. They’re watching darts.

The atmosphere feels like a night at the bar with some of your friends and a bunch of people who will become your friends. Beers, chants, dancing. Many of the fans are in costume: M&M’s shirts, the Average Joe’s dodgeball jersey from Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story. It’s the first night of the Professional Darts Championship’s North America stop, where some of the best players in the world face off against the best in the continent.

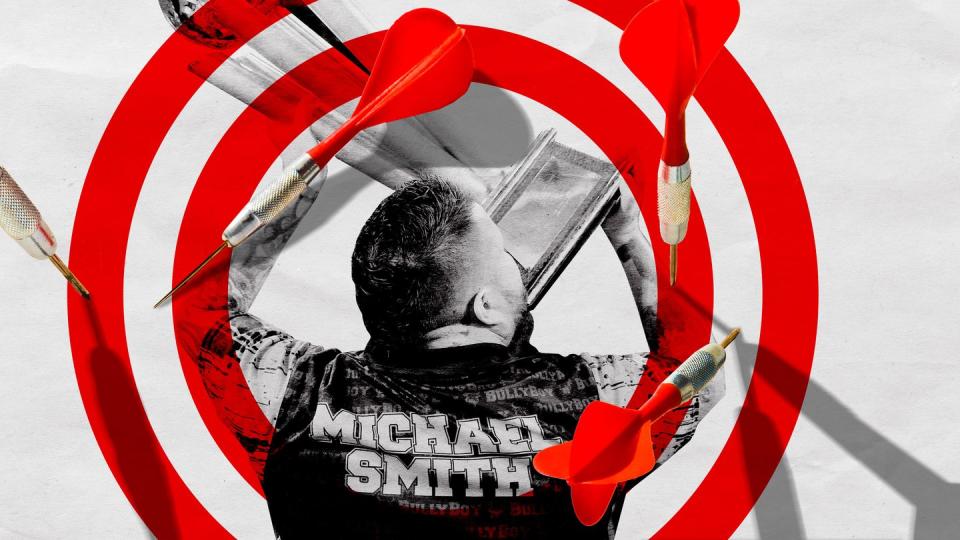

Fans waited hours to see the world’s top darts player: Michael “Bully Boy” Smith. And, finally, there he is standing to the side of the stage. The lights go down in the theater. Smith is playing the last of eight matches of the night. He entered as a world champion, the event’s reigning champion, and the number-one ranked player in the world. He’s the showcase matchup to close out the evening. Fans expect him to dazzle.

Smith brings an air of stoicism with him. He’s perfectly manicured and tailored, with a coiffed faux-hawk and tightly lined-up beard. A small gold chain pokes out from under his jersey, a shiny polo shirt adorned with gaudy designs, colors, and sponsors. A smile breaks through Smith’s small mouth as he waves to his adoring crowd. Smith isn’t the showman that other dart throwers are. He’s a deadly executioner people come to watch as he tries to reach perfection—a score of 180—one turn after another.

In America, professional darts is still a niche sport, if it’s known at all. But the game is hugely popular: An estimation in 2019 said that more than 17 million Americans play, which makes sense. It’s a perfect sport to play by yourself or with some friends at the bar on a Wednesday night. The rules are pretty simple for 501, the main version of the game: Get to zero first. In other parts of the world, specifically mainland Europe and England, darts is more than a game. It’s big business. Darts players are celebrities in Europe. They’re famous athletes that prop up businesses with their endorsements for darts companies and watches, which get plenty of camera time.

Smith has made a life out of not only hitting the board but hitting the minute spaces on it. He’s won more than £900,000 in purses playing in the annual Professional Darts Corporation World Championship event alone. Those winnings don’t include endorsements and what he’s won playing on the PDC tour, which plays nearly every week in cities across the globe. He has legions of fans who buy his darts and shirts. He’s a near-global superstar, but professional darts hasn’t taken off in America—yet. But it’s slowly growing and has a base of players who play the game casually or in leagues throughout the country.

Unlike basketball and football, though, the rules are rather simple once you see a game. The game played at tournaments is a race to zero with one catch: You need to hit a double (the outer ring) to close the set. Smith, for years, has been able to close a set almost as fast as anyone. He’s won just about everything save the equivalent of golf’s Masters and the rest of the majors rolled into one event: the PDC World Championship. Until this year.

And now he’s here in New York under the bright lights—literally under Billy Joel—ready to throw some darts and show these people how damn good he is.

He stands and waits for the game to begin.

The day before the tournament, Smith meets me in a hotel lobby dressed in what I would term English casual: sneakers, black fitted pants, and a track jacket. He appears more like one of the St Helens rugby players that he cheered for as a child than what we’d picture when we think of someone who throws darts for a living: large belly, sloven appearance, scraggly facial hair, and baggy clothes. Smith sits on a seat on the balcony overlooking the hotel restaurant. He drags from his vape pen. I ask him about St Helens, the town of just more than 100,000 people where he grew up in England.

“It has its bad areas, like everywhere does, and good areas,” Smith says, leaning forward in his seat, the almost-summer heat of New York City breathing down on us. “Where I grew up wasn’t one of the nicest places to live, but that was home for me. Everyone’s behind you. You follow darts or rugby. Now rugby comes first, I think, in St Helens.”

Smith was raised in a public housing neighborhood known as a council estate. His parents bought a home, and his aunt did as well. He had friends in the neighborhood. A tight-knit-community kind of place. At the same time, the police often raided homes in the neighborhood looking for drug dealers and addicts.

Smith is quiet and relaxed. He’s unfazed by the Garden. MSG. The place where Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier fought for the first time. The home of the New York Knicks and Rangers. The Theater, where he’s going to throw, is where Eddie Murphy performed and recorded his seminal stand-up special Raw. He’s a soft-spoken man from St Helens here in New York to play darts, promote the game, and hopefully win some money to provide for his family.

But it’s not just another stop. Whether Smith wants to admit it or not, this is his moment. He’s the newly minted world champion. The kid who didn’t finish any formal schooling and used to watch police drive down his street to make drug busts earns life-changing money by throwing darts at a board. Then there’s the way it happened.

Smith won the 2023 PDC World Championship in January. It was his third final in five years. He’d found heartbreak the previous two times, losing and wondering if he could pick himself back up to do it again—to travel the world for a year, far from his family, practicing darts for hours only to see the hard work slip away on the biggest stage and at the biggest moment. His son urged him to stick it out. No quitting. Not yet.

It paid off.

He threw a perfect game against three-time champion Michael van Gerwen, who is considered one of the greatest darts players ever. A perfect game is nine darts, three turns, to get from 501 points to zero and ending with a double—either the outer ring of the dartboard or the red part of the bull’s-eye, which is actually a double bull and worth 50 points. There is another ring around the inside of the board, and if a dart lands in that space, it’s triple the points, which makes triple-20 the most important mark on the board since it can count toward 180 points on one turn.

It happened like this:

Smith approached the oche, the line darts players stand behind. He took a breath. With two 180-point turns behind him, he needed 141 points to hit his goal. The first dart rolled out of his left palm to his fingertips and he grabbed it with his right hand. It flew.

“I’ve never seen the like!” former professional Wayne Mardle shouted.

Smith sent the first dart into triple-20, 60 points. Easy.

“Come on, Bully Boy,” Mardle screamed.

Smith hit triple-19, the dart sliding in. Double-12 was all that was left for a perfect leg. The final dart landed right on target.

“That is the most amazing leg of darts you will ever see in your life,” screamed Mardle. “I can’t speak! I can’t speak!”

Smith turned with a wry smile and pumped his left fist to the crowd as he walked to grab his darts. Almost nothing fazes van Gerwen, but you could see disbelief in his eyes as he shimmied his shoulders. Smith took a lead in the set, 2–1, and still needed to win five more legs to claim his title. He took van Gerwen’s best shot and outdid him. The pressure shifted from one darts player to the other. All those darts and that talent finally paid off on the biggest stage—on the stage where he’d lost so many times before.

It took less than a minute.

But the tour didn’t stop. Soon after winning, he was back on the road, flying across the globe to play and promote the game. He traveled nearly nonstop all year. His wife and children came along, thankfully, for the New York trip.

Time is tight today. He has places to be. We talk for a bit before he and a few other PDC professionals have to head to a car downstairs, which will take them a few blocks to where fans are waiting for a VIP meet and greet. I decided to walk and meet them over there.

For the event, Smith is wearing his darts shirt under his track jacket. He doesn’t want to be noticed while on the street on the way to the event. It sounds a bit silly, a professional darts player being accosted on the street for selfies and autographs, but fans wait at airports and outside hotels for a chance to meet their dart-throwing heroes. On top of that, the paparazzi in England and across Europe, where tabloids rule the media landscape, love getting into the personal lives of professional athletes and causing a stir in any way they can.

“When we first moved, we had people knocking and asking for pictures and autographs,” Smith says. He prefers being alone. And today he’d rather be with his family on their farmstead in his hometown. Someday the 33-year-old wants to own a bull he can call Ferdinand, named after the 2017 children’s film, which itself is an adaptation of the 1936 children’s book The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf. The story is about a bull who prefers to sit under a tree and smell flowers rather than butting heads with other bulls or chasing down matadors.

Smith loves animals. They bring him peace. And they’re how he got the nickname Bully Boy.

The story goes: One day, Smith went to work on a farm that belonged to a security guard who worked at his aunt’s and mother’s pubs. The cows were having calves, and the babies needed tags. But the security guard grabbed the wrong tag for one of the calves and left to get the correct one. As he did so, Smith had the baby cow in a headlock for 25 minutes so it could get its identification. When the security guard returned, he found Smith holding the calf with his legs wrapped around it and a finger in its nose. Smith was covered in cow shit and on his back doing his best to wrestle a four-day-old cow. The security guard called him a bully, so when the time came for a nickname for darts, Smith knew what he wanted: Michael “Bully Boy” Smith.

At the bar, a small, close-knit community of darts obsessives wait. They’re dressed as if it’s gameday and their team is on, but they’re hoping to get a word, photograph, and autograph from Smith and the other European tour members. People hold beers while the line snakes around the bar. Smith and the other darts players sit awkwardly at some tables with Sharpies in hand. It’s not a big group, but these VIP tickets afford the fans this chance to meet their favorite athletes. Some regulars sit at the bar and watch ESPN talking heads spout off about the NBA Finals, unaware of what is happening around them.

Smith does his duty. He’s the quietest and most reserved of the pros, sitting in the darkest corner. It’s not arrogance but shyness. You can see he’s visibly uncomfortable with people wanting his autograph or photo. He has a small smile, and yet his humility is what draws fans to him. He could have been your friend. Or your neighbor. He’d prefer to drink a beer quietly at a local pub.

The man who would become a World Champion darts player didn’t like darts.

Smith’s hometown of St Helens sits between Liverpool and Manchester in the northwest of England, where rugby is king. He wanted to play rugby, of course. St Helens R.F.C. is one of England’s most successful and fiercely supported rugby teams. It won four consecutive championships from 2019 to 2022, bringing its total to 17 league championships, along with 13 Challenge Cups. Smith’s father played darts, and his family owned pubs in the area, but Smith didn’t fancy it. “I hated the sport,” Smith says. “I thought it was boring.”

And he might still feel that way if not for a fateful accident.

Smith was late for school, as usual. He and his friends were riding their bikes and popping wheelies when Smith lost control and jumped off, holding the handle bars and running behind the bike. Thinking he was going to fall, he pushed the bike away and pressed his foot into the ground to stop. Snap. He crawled to collect his bike, slumped his body onto it, and pushed his way home. The next day, he stumbled as he navigated his way to an X-ray machine. And there it was: a broken hip. He’d be on crutches for months. No playing football on the small patches of grass. No rugby. No riding bikes. Smith needed something to do.

Smith’s father played darts in a local league, and the young Michael would watch him practice on the dartboard on the back of the front door. When Smith could put some weight on his foot, he took the darts and began to throw himself. At first, his father supervised, making sure he hit the board instead of the door or one of its ornamental windows. Smith stood and threw while his dad walked back and forth to the board, pulling the darts for him. Something about the ritual connected with Smith. It gave him purpose and focus while also allowing him to be alone while practicing. He threw for hours. He banged up the board. When he could finally start to hobble back and forth, he pulled the darts on his own. Four weeks after throwing his first dart, he hit his first 180.

For Smith, a solitary kid by nature, darts proved the perfect sport. He practiced alone. He didn’t need friends or family to play with. It took over his life.

“I’d go to school and think about darts instead of English or math or geography,” Smith tells me. On an English exam, he had to write what he wanted to be when he got older. His answer? Professional darts player. Smith wrote “maybe ten words and closed it.” His teachers didn’t grade it. Eventually he went to school for joinery, and on the day of his exam, he skipped to play in a darts tournament.

Darts provided a way out of Smith’s neighborhood. He’s said before that he could have gone down two paths: death or jail. Darts offered a third. He knows people who have killed themselves. Others went to jail, including some family members. Darts provided an escape from that. He couldn’t get caught up in what was happening down the road from his house if he was practicing or going to tournaments. While still recovering from his broken hip, Smith entered a youth darts tournament and won.

As the sport took on more importance in his life, his family decided they’d help him reach his goals of going professional. His parents took on more work and drove him to tournaments around the country. They told him he could live at home for free if he went to college. He didn’t and had to pay rent.

“I had nothing else. I didn’t want to work. I was too lazy to get a real job,” Smith says. “I was working in Mom and Dad’s pub, and I left school with no education. Really no qualifications. So I had nothing. I had to work as hard as I could. It was either that or go back down to the path that I could have chosen before.”

Back at MSG, the crowd is in a frenzy as Smith walks up to throw. He’s facing off against Canadian Jim “the Gentleman” Long. The pair met in the same tournament in 2019. Smith won, 6–4. This time there was an expectation in the air that an upset could be in the works.

Shouts of “Come on, Bully Boy!” erupt from the crowd as he approaches the oche for the first time. He turns his left foot slightly to place it against the oche and looks straight at the board. His darts rest in his left hand, and he stares at the board with his mouth slightly open. In succession his right hand pulls a dart from his left. He throws the dart straight into the board—and quickly grabs the next dart with his follow-through. Smith’s head never moves when he’s throwing. There’s rarely a reset. One dart after the next. Bang, bang, bang.

In the first leg, Smith is in command. He hit his first 180 on his third turn, taking control of the board. The darts were hitting their mark. He set himself up for a checkout of 41. Easy. Or it should be. He hits a 20 and then a 5, leaving 16. He needs a double-8. That’s an easy shot. But somehow he misses it. He can’t close the game. Long walks up with 97 to go. Three darts and he’s done. Smith misses his chance to set the table and get himself ahead. It feels like an omen.

When Smith is throwing well, there’s confidence in each throw. The darts land on the board with authority. He rarely changes his expression. Each thud into the cork sounds like a single bass-drum kick. The darts cluster neatly next to one another. The outs come quick. But on this night, each turn saps the confidence from Smith. He misses critical darts, and Long pounces on the opportunity. Smith shakes his head. He grabs his darts as if he’s angry at them. Even the five 180’s he throws don’t seem much more than a tease. When it comes time to close, Smith misses a dart he’s hit millions of times over the course of his life. It’s inexplicable.

With each game and successive win, the crowd grows in anticipation of an upset. There are still shouts of “Come on, Bully Boy!” But more and more the screams and yelps come when Long is leaving the board, because he’s done just enough to keep himself in front—to put the pressure on Smith and eventually to close out another game. Even as Smith looks as though he’s getting back into the match, Long has a 115 checkout. Smith plays with the sleeves of his shirt and at one point bites off a piece of string from inside his left forearm.

Smith looks for anything. He needs something to change. In the seventh leg, with Smith down 4–2, Long trounces him. It’s not close. By professional darts standards, it’s an ass-kicking. Long misses a routine checkout and Smith still has 300 points to go. Long misses his next dart for an out. He smiles. The next dart lands in. Bang. Leg over.

The final game is a formality. Smith doesn’t have it tonight. The world champion can be beat. It doesn’t matter who you are: The board is unforgiving.

You Might Also Like