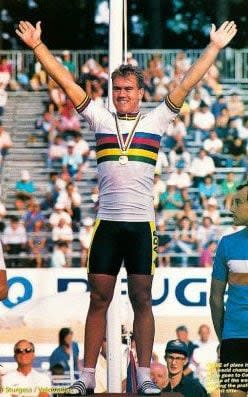

Former world champion Colin Sturgess endured his life falling apart but is now back on track

For a long time, Colin Sturgess struggled with feelings of self-loathing when he watched the track world championships, but last week the competition provided him with sanguine entertainment.

Rather than blame himself for decisions that contributed to the unravelling of a hugely promising career, he was able instead to find pride in the memory of the success that he enjoyed at the same event three decades ago, while also looking optimistically to a future mentoring the next generation in the sport.

Given that this former world champion’s life fell apart so dramatically that only five years ago he was homeless and suicidal, such a recovery should serve as the most encouraging news to fans of the sport.

For the 48-year-old Sturgess, now directeur sportif with the domestic Metaltek-Kuota team, it is certainly a source of quiet satisfaction. “It is, yeah,” he says, speaking from the family home in Leicester. "I don’t like to self-aggrandise, but I do feel quite proud of the fact that five years ago I was living in a car, basically homeless in Australia and now I’m helping to run one of Britain’s more successful teams. It means there is hope and direction in my life again.”

To understand how far Sturgess fell, you need to appreciate both the height that he reached and how much more he seemed destined to achieve.

Raised in South Africa to British parents, he returned home with the family to Leicester because they felt he could realise his potential only in their parent country. At the time, Chris Boardman was the outstanding talent in the British junior set-up, having set multiple time-trial records and dominated the endurance scene. In Sturgess, however, four months younger than Boardman, the future Olympic champion met his match.

In the individual pursuit, both men’s track specialism, Sturgess beat Boardman at junior and senior national championships and again at the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, in which Sturgess won silver aged only 17. “Chris was the great hope,” Sturgess recalls. “As a schoolboy he’d won umpteen races and done fantastic times in time-trials. So I knew that this guy was supposed to be something super special and I came along and scuppered his ambitions.”

Sturgess was celebrated for his showmanship on the bike. Rather than adopt conventional tactics for the individual pursuit, which called for a steady, constant pace, he preferred to hold back and kick hard on the last lap, introducing a dramatic twist for the fans’ entertainment.

Walking out on the Olympic programme. That was a massive, depressive state, unmedicated, not really knowing what was happening

He managed the trick perhaps most memorably when he won the world title on a balmy night in Lyon in 1989. Trailing the Australian Dean Woods by more than a second approaching the bell in the final, Sturgess produced such a burst of acceleration that he slowed before the finish and still won by 1.66sec. ‘‘The tactic backfired a couple of times but nine times out of 10, it meant people enjoying watching me because I had this electrifying finish,” he says, with a chuckle. “And it put the fear of God into many opponents, because it almost psyched them out.”

Sturgess’s talent earned him contracts with two strong World Tour teams, including Greg LeMond’s ADR squad, in an era when few Britons were invited to elite road racing. He won bronze at a subsequent world championships, too, before dropping out of cycling to return to his studies, having become disillusioned with the politics, insecurity and drug-taking in the sport. EPO was being introduced into the peloton at that time.

I went out one night with a bottle of vodka, driving 100k down a dirt road, consumed with suicidal thoughts

With an English literature degree to his name, he emigrated to Australia and worked as a cycling journalist, but returned to the sport in the late nineties, winning silver at the 1998 Commonwealth Games as part of the team pursuit quartet that included the young Bradley Wiggins. By then dividing his time between Sydney and the British team’s base in Manchester, Sturgess moved on to the new Lottery-funded Olympic programme, only to quit, suddenly, having fallen out with management over money. He walked out on the sport for a second time.

At the time, he felt it was a principled decision, but realised later that it was more the result of a depressive episode that was symptomatic of a then-undiagnosed bipolar disorder. In retrospect, he can see that such dramatic emotional shifts defined much of his early life.

As a 20-year-old professional living alone in Belgium, for example, he became so despondent that he could summon the energy to train for only an hour a day and took to his bed at dusk. For a typical manic episode, he cites the episode on his comeback when he embarked on a needless but brutal five-hour training ride on the morning before the New South Wales track championships, at which he then won the points race.

“I can look back and look at aspects of my career and my life and, say, yeah, that’s obviously a manic phase and that’s a depressive phase. Walking out on the Olympic programme. That was a massive, depressive state, unmedicated, not really knowing what was happening. A certain amount of self-blame has gone [over such incidents], but I still look back at things like that and think, damn, what if?”

A pertinent question he asks himself is whether, given his emotional fragility, he might have achieved more had he not been subject to such pressure at such a young age. Conversely, he knows also that his condition might have actually contributed to his success. A personality given to extremes is especially suited to the exceptional demands of endurance sport. “Did I do too much too young? Could that have been a catalyst for my bioplar diagnosis later in life? Or was the bipolar the reason I was so good as a youngster - high achievement, high goal settings, the periods of intense creativity... ? I don’t know.”

Even once his condition was identified, Sturgess, inevitably, could not prevent it from impacting adversely on his personal and professional life. He lost two marriages, the first of which had lasted nine years, producing a now 12-year-old son. The second fell apart after four years.

A second, successful career in the Australian wine industry petered out, too. Though he won national awards for his oenological work, which included wine-making and compiling exclusive wine lists as a sommelier, his compulsive streak meant he was prone to drink the produce to damaging excess, and eventually cost him his job at around the same time as he split up from his second wife.

Distraught and with nowhere to turn, it was then that he ended up homeless in Sydney, living in his Mitsubishi saloon and overwhelmed with thoughts of talking his life. “Oh, I thought about it loads of times, mate. I went out one night with a bottle of vodka, driving 100k down a dirt road, consumed with suicidal thoughts.” The car tumbled 20ft down an embankment in the Hunter Valley, prime wine-making territory to the north of the city. “Landed on its roof. I only survived because I wasn’t wearing a seat belt. As it landed, it shot me out.”

Eventually word got to his parents, Ann and Alan, once both keen club cyclists, that their only child was destitute and they arranged to fly him home. Four years on, he still lives in their terraced house - a source of regret when his son lives in Australia and their relationship is restricted mostly to conversations online - but Sturgess has nonetheless managed to lay down the foundations for a new life.

With Metaltek, he is responsible for a team holding their own at the highest level of the domestic road-racing scene. He undertakes private coaching alongside that work, and still finds the time to ride intensely. He even briefly managed to land a semi-professional contract which took him to the Tour of Morocco last year, though a crash and injured knee put paid that to that particular comeback.

Content instead to pass on the benefits of his experience to some of the best young British talent, and hopeful that it will lead to further work in the field, he was able recently to come off medication for his condition for the first time in 12 years. “I’ve been given another crack at the whip in the sport and I’m grateful for it. I’ve been through a lot in cycling and I’d like to think I have a lot of knowledge to impart. I certainly get great satisfaction from doing it.”

One crucial responsibility, he says, is to ensure riders avoid some of the critical mistakes that he made. You hope that they are grateful for the privilege of listening to him.