Floods, fire and tornadoes: Iowa Cubs' 1993 championship season was unforgettable

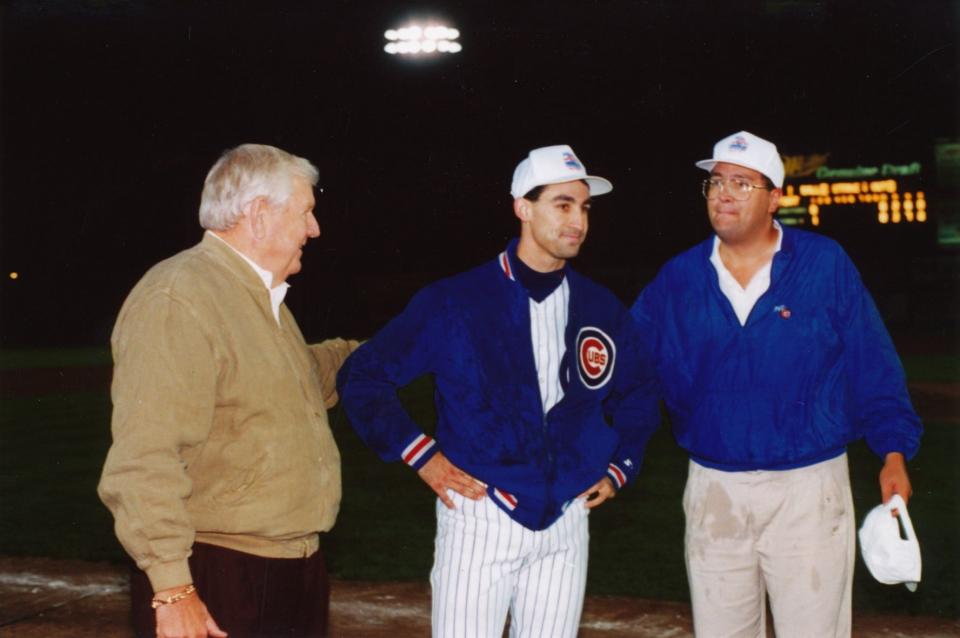

One of Iowa Cubs president Sam Bernabe’s favorite pictures hangs behind his desk in his first-floor office at Principal Park. The photo shows Bernabe standing at home plate at what was then known as Sec Taylor Stadium, celebrating the team’s American Association title as a bottle of champagne is poured over his head.

“I ended up wearing most of it,” Bernabe says with a smile.

The accomplishment certainly called for a party. The championship was a first for the franchise (the Cubs are still searching for their second). But it was hardly the only memorable moment of that summer. There were floods, a fire, tornados and a triumphant home run to cap the season.

“There were all sorts of chaos going on around us,” said catcher Matt Walbeck.

It’s been 30 years since that championship season, and it remains a special memory for everyone who was a part of it. As the 2023 Cubs enjoy a successful season, perhaps history repeats itself and another championship is in the works for the Triple-A affiliate of the Chicago Cubs.

'We had high hopes for a better team than we had the year before'

The Cubs were coming off a disastrous season that saw them tally just 51 victories in 1992, a team record for futility that stood for more than two decades.

But by the following summer, things had drastically changed after a massive roster makeover. The Cubs brought in experienced players, including infielder Craig Worthington and pitcher Ed Vosberg. And they started to move big-time prospects up the organizational ladder, including pitchers Turk Wendell and Steve Trachsel, infielder Matt Franco and outfielder Eddie Zambrano.

“We had high hopes for a better team than we had the year before,” said former Iowa Cubs radio broadcaster Deene Ehlis.

New Iowa manager Marv Foley preached an old-school approach of "fundamentals-first" baseball. To get that message across, Foley came up with a list of tasks his hitters had to accomplish in certain situations. They ranged from driving in a runner from third base with less than two outs to moving a runner from second to third with nobody out.

Foley wrote all the tasks on a sheet with the hitter’s names and displayed it prominently in the clubhouse. He even brought it on road trips. If a player accomplished a task, they earned 50 cents. If they failed, they had to pay 25 cents. The money to pay the players came out of Foley’s pocket. The goal was to encourage a selfless style of play.

“It was just old-school baseball,” Walbeck said.

The approach not only worked but also helped the players bond. The Cubs were dominant on the field and close-knit off the field. They hung out in large groups, hitting bars together on road trips and restaurants while in Des Moines. The ringleader was Wendell, a bizarre character who leaped over foul lines, ate black licorice by the bushel, and brushed his teeth between innings.

Wendell was the team jokester, taking his fishing pole on road trips and tying a $5 bill on the end of it and casting it in the airport. Wendell and his teammates watched strangers chase down the bill while he reeled it back in. A few times, his teammates had to come to his defense when an angry victim of his joke realized a prank was being pulled.

“We jelled really well,” Wendell said.

The Cubs were close, and they were tough. During a series with the Nashville Sounds, Zambrano, the team's star, got plunked with a pitch. Foley figured it was intentional. So he ordered Walbeck to retaliate by having Iowa’s pitcher hit the first and second batters in the following inning. Walbeck relayed the order to the pitcher. It sent a message to the Sounds as well as Zambrano and his teammates. No one was going to mess with the Cubs.

“That was the way we played,” Walbeck said. “There was an intimidation factor.”

That was a characteristic that served them well in 1993.

Floods, fire, tornadoes and a late truck

Bernabe, the team's general manager 30 summers ago, was furious when the 1993 schedule was released. It called for his team to take a long road trip right in the heart of the summer, a prime ticket-selling period for his team. When Bernabe saw the giant gap between home games on the schedule, he voiced his displeasure during a league meeting.

“I just raised seven kinds of hell,” Bernabe said with a smile.

The time away turned into a blessing when floods ravaged the state of Iowa. The infamous floods of 1993 destroyed houses, businesses and lives. Sec Taylor Stadium (later renamed Principal Park) is located at the confluence of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers. Water covered much of the field at the ballpark, other than the pitcher's mound. Incredibly, no Cubs home games were lost due to flooding.

“It looked like an island out there,” Bernabe said. “My groundskeeper at the time ... went out with an inflatable palm tree and a lawn chair and sat out there like he was sunning himself on the beach.”

When the floods breached Des Moines Water Works, residents were without running water. Ehlis, on the road with the team, called home and talked to his wife. She had taken their kids to the backyard in their swim attire and bathed them in drain water.

Players on the road trip didn’t realize how bad things were until they gathered at a bar with a television. There, on ESPN, was their minor-league ballpark.

“It was completely underwater,” Trachsel said. "That was the first we had heard of it and how bad it was."

Register reporter Randy Peterson, the Cubs beat reporter at the time, took a boat to the stadium for a story while the team was out of town. A clubhouse attendant grabbed some of the team’s gear and equipment in the locker room and prevented it from getting damaged.

But because of the long stretch of road games, the water was out of the park by the time the team returned to Des Moines. No games were postponed or canceled due to flooding. Players and coaches had to receive tetanus shots to be on the field because it had been covered by floodwater. Even a concert by The Temptations, planned long before the floods, went on as scheduled. In light of the tough times, fans got in for free.

“Everybody was struggling,” Bernabe said. “Nobody was thinking about baseball.”

The floods didn't slow down Iowa's season. But that doesn't mean there weren't hiccups. The Cubs were forced to postpone a game when a building with toxic chemicals a couple of blocks away from the stadium caught fire. Winds were blowing toward the ballpark, so everything in its path was shut down. On two occasions, the team was forced to evacuate the stands due to tornado scares. Fans huddled together throughout the park − including the team clubhouse − to wait it out.

Another game was postponed when the team equipment truck was delayed getting back to Des Moines from a road trip. Bernabe sent his staff to a local sporting goods store to stock up on gloves, cleats and other gear. None of the equipment was broken in, and there wasn't enough time to do so by the time the team took the field. So the Cubs played a doubleheader the following day.

"(The players) appreciated the effort but they said, 'Sam, we can't do that,'" Bernabe recalled.

Meanwhile, the 1993 Cubs kept rolling.

Tuffy Rhodes trade becomes a turning point

The Cubs' success was a positive story in a summer of devastation. Iowa had a powerful lineup and a strong pitching staff that frequently allowed the Cubs to come from behind. Zambrano, the league's most valuable player in 1993, belted 32 homers and drove in 115 runs. Outfielder Kevin Roberson hit .304 with 16 homers. On the mound, the Cubs had four pitchers win at least 10 games (Trachsel led with 13 victories). Wendell took a perfect game into the ninth inning on the road but lost it when a ball bounced off third base and rolled into the dugout.

The club gained momentum in July when the Cubs traded for outfielder Karl Rhodes. Nicknamed "Tuffy," Rhodes had come up with the Astros and played in the big leagues for parts of 1990-93. Rhodes was granted his release in April and landed with the Kansas City Royals on a minor-league deal later that month. He was off to a strong start with the team's Triple-A affiliate in Omaha when the Cubs visited town in July.

During the trip, the Cubs pulled off a three-way deal with the Royals and New York Yankees. The Cubs got Rhodes and gave up pitcher Paul Assenmacher. Rhodes first got wind of the trade before a game against the Cubs when Iowa pitcher Chuck McElroy mentioned there had been a deal. The outfielder didn't realize he was the one who got traded until he returned to the clubhouse. All Rhodes had to do was pack his things and switch clubhouses.

He was well aware of the success the Cubs had enjoyed that season.

"I knew it was going to be hard to beat us," Rhodes said.

Rhodes was hitting .318 with 23 home runs and 64 runs driven in at the time of the trade. He bolstered an already electric lineup. Rhodes moved to center field when the Cubs picked him up and took the team to another level. Iowa finished the regular season with an 85-59 record and won the Western Division to advance to the American Association championship against Nashville.

"Once we got Tuffy, that was the point where you just knew we had not only a good ballclub but a championship-caliber club," Ehlis said.

The Cubs were set to play a best-of-seven series with the Sounds. The Chicago Cubs, meanwhile, were struggling, and the postseason was out of reach. So Cubs management decided to keep Rhodes and many of Iowa's stars in the minors so they could make a run at a title.

Chicago planned to promote those top players to the major leagues after the American Association championship series was complete. None of them knew it was coming, except for Trachsel, who was told he was headed up after following his start in Game 6 of the series. Trachsel promised not to tell anyone else so they could focus on the series, which was tied at three games apiece and heading for a decisive Game 7.

"I'm sitting in the dugout, hoping, praying that we win Game 7, but also going, 'Oh my God, I'm going to the big leagues after this game and nobody knows,'" Trachsel said.

Game 7 turned into a memorable night for everyone on Iowa's roster.

Rhodes' historic home run in Des Moines kicks off a huge celebration

The final game of the series was another back-and-forth battle between Iowa and Nashville.

Iowa took a 1-0 lead on a sacrifice fly by Zambrano in the first inning. Nashville jumped ahead with a two-run homer by Norberto Martin. The Cubs then tied it in the seventh inning on a sacrifice fly by Franco.

It remained tied until the bottom of the 11th inning, when Rhodes stepped up to the plate to face Nashville right-hander James Baldwin. Rhodes fell behind in the count after a first-pitch strike, but he knew Baldwin had a tendency to throw curveballs in that situation. The Iowa outfielder also noticed Baldwin had a "tell" for the pitch and spotted it before the next offering. Rhodes sat on the off-speed offering and waited for Baldwin to deliver it.

“I just told myself, ‘Don’t get too far out in front, just stay back up the middle and hit it over the left-center field wall,’” Rhodes said.

That’s exactly what he did. Rhodes crushed the offering deep into the Des Moines sky and over the fence for a game-winning, walk-off homer. As the ball cleared the fence, Nashville’s left-fielder threw his glove. Meanwhile, Iowa players stormed the field and waited for Rhodes to reach home.

“When you hit first base, reality sets in,” Rhodes said. “Then I couldn’t get around those bases fast enough.”

Bernabe, who was waiting near the third-base dugout along with league president Branch Rickey, raced out to the field for the trophy presentation. Iowa outfielder Doug Jennings lifted Rhodes into the air and helped carry him off the field. Players and coaches went in and out of the clubhouse to take multiple curtain calls from the announced crowd of 4,317 fans. Ehlis, in the broadcast booth, let the crowd do most of the talking.

“It sure sounded like 10,000,” Ehlis said.

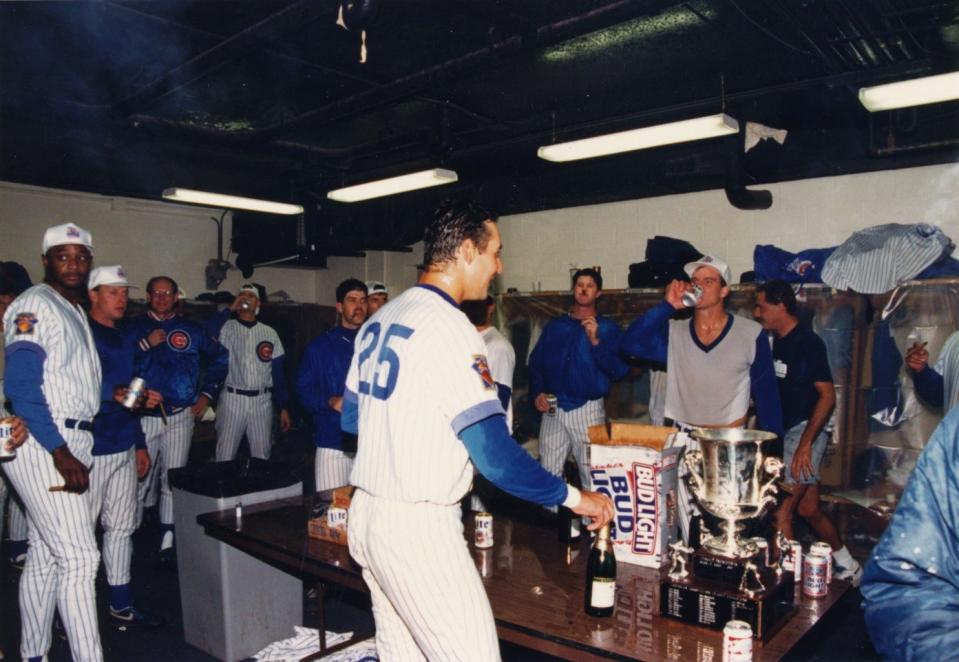

The celebration was just as big in the clubhouse. Wendell hid in the trainer’s room as players were summoned back to see him. When they arrived, he sprayed them with champagne. The team uncorked bottles, lit up cigars and opened beers around their lockers. Foley went to his office and called all the players who were headed to the majors, one by one, into his office.

“It was the icing on the cake,” Rhodes said.

The party kept going outside the park and all evening. The team, players and front-office members retreated to a downtown Des Moines bar, Johnny’s Hall of Fame, for a postgame party full of snacks and drinks. Bernabe estimates his tab was well over $2,000. When closing time rolled around, the doors were locked and players were allowed to stay and celebrate their title. Many stayed as late as 4 a.m.

“I don’t think we went to sleep that night,” Walbeck said. “That was a good ol' party we had back before social media and cellphones. So we could kind of do whatever we wanted.”

The next day, Rhodes and the other players summoned to the big leagues packed up their things, many leaving their Des Moines apartments for good. They hit the road for Chicago, honking and yelling at each other as they passed one another on the road.

"It was a great end to an incredible season," Rhodes said.

2023 Iowa Cubs try to follow in the footsteps of the 1993 team

The home run remains one of the marquee moments of Rhodes' career. He has others to choose from. The following season, he belted three home runs on opening day for the Chicago Cubs. Rhodes later went overseas and even became the single-season home run record-holder in the Japanese League.

He's retired now and is building a house in Costa Rica to go along with houses in Ohio and Arizona. People still ask him about that home run in Des Moines.

"I don't think that's ever going to go away," Rhodes said.

The Cubs have made it back to the championships two other times since 1993, most recently in 2004, both times falling short. Bernabe believes this year's team is just as good as that 1993 squad and could win a championship.

"No question about it," Bernabe said.

A lot may depend on what the Cubs do for the remainder of the season. The days of leaving players in the minor leagues to chase a championship are mostly gone. The focus is on development of prospects and helping the big-league team win.

With the Chicago Cubs in a battle for a postseason spot, some of Iowa's best players could be pulled away at a moment's notice. That's what makes winning a championship in the minor leagues so difficult. And it's why that 1993 season is still so special after all these years.

"It was a great summer," Rhodes said.

Tommy Birch, the Register's sports enterprise and features reporter, has been working at the newspaper since 2008. He's the 2018 and 2020 Iowa Sportswriter of the Year. Reach him at tbirch@dmreg.com or 515-284-8468.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Iowa Cubs won 1993 title in crazy summer of floods, fire, tornadoes