FIFA’s Single-Entity Women’s World Cup Business Plan, Explained

FIFA has taken a dramatically different commercial approach to this year’s Women’s World Cup, which starts on Thursday, July 20 in the joint-host countries of Australia and New Zealand. For the first time since the event’s introduction in 1991, this year’s tournament has operated as its own distinct commercial entity.

From separating the men’s and women’s tournaments’ television rights to investing substantially more in the overall women’s event, here’s how and where the global governing body’s strategy shifted most.

More from Sportico.com

New Zealand's Eden Park World Cup Venue Adapts Amid 'Stadium Wars'

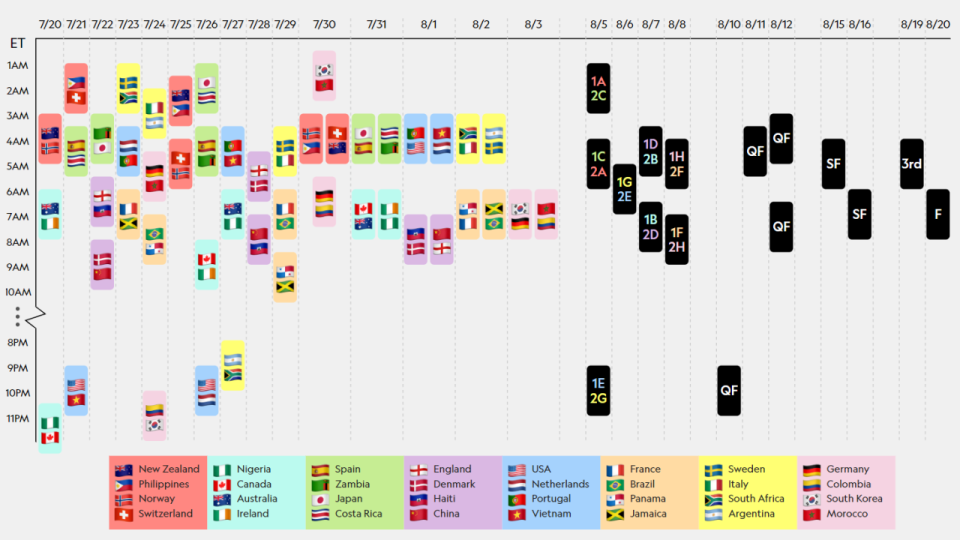

Women's World Cup Setup Takes 'Travel Soccer' to Whole New Level

Media Rights

FIFA has historically included the women’s tournament as an add-on to the media rights deals for the men’s World Cup. The organization decided to spin the property off after the 2019 women’s tournament saw a record 106% increase in television audience globally over the 2015 edition, hosted by Canada. The 2023 Women’s World Cup, therefore, is the first time soccer’s governing body has sold the competition’s broadcast rights on their own.

Those rights are sold on a regional basis, and a few existing deals were already in place. In the U.S., for example, the tournament’s rights remain bundled with the men’s. In 2011, Fox Sports and Telemundo paid a record sum of about $1 billion to broadcast the men’s and women’s World Cups from 2015 through 2022 in the U.S. FIFA later extended that agreement for one more cycle to run through 2026, an agreement reached before the organization decided to untangle the television threads.

However, on the other side of the Atlantic, FIFA’s plans to unlock more value from the women’s tournament meant new deals across the board. It began publicly pushing broadcasters to pay more for the women’s rights in 2022. But those demands were met some resistance from European broadcasters, who were not immediately willing to pay the price FIFA had set for the rights, prompting backlash from FIFA president Gianni Infantino. In June, Infantino threatened the broadcasters with a blackout unless their “unacceptable” bids were improved.

According to the FIFA president, Europe’s top soccer nations (the United Kingdom, Italy, France, Germany and Spain) had offered only $1-$10 million apiece for the women’s rights, compared with $100 to $200 million they offered for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar for the men’s tournament.

Finally, 36 days before kickoff, FIFA extended its agreement with the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), allowing EBU’s free-to-air linear networks across 34 European territories to broadcast the Women’s World Cup. While the amount the broadcasters agreed to pay was not disclosed, FIFA said EBU member networks from Germany, the UK, France, Italy and Spain will work to help market the tournament across all their channels as part of the a long-term strategy to “promote the growth of the women’s game in Europe.” FIFA did not respond Sportico’s request for comment on the value of the final deals.

According to FIFA, this year’s tournament is expected to reach a global audience of two billion people.

Corporate Sponsorships

In late 2021, FIFA announced it would also be separating the women’s and men’s corporate sponsorships rights after long selling the former as part of package deals with the latter. Esports would also stand alone under the new model, which went into effect in 2023.

In doing this, FIFA accomplished two key things. First, it opened the door for brands that are potentially only interested in sponsoring women’s soccer competitions, significantly widening the pool of potential corporate partners. Also, unthreading the three verticals from one another also changed the price point corporate sponsors were being asked to consider. Paying for the rights to just one tournament—as opposed to two or even three—was theoretically more financially feasible for a much bigger group of brand partners, especially considering that the FIFA men’s World Cup is likely one of the most expensive sponsorships in all of global sport.

By doing both, FIFA would be able to get a better sense of not only brand interest in the women’s tournament as a standalone asset, but also its value in the free market.

FIFA’s corporate partners get access to official marks, stadium and website exposure, hospitality and marketing opportunities as well as preferential access to broadcast advertising inventory in the standard rights package. There’s also at least some room for creativity, as FIFA allows partners to “tailor their sponsorship according to their marketing strategy and needs,” per its website.

Soccer’s global governing body made a number of packages available for the women’s tournament and quickly secured Visa as its inaugural global women’s soccer sponsor.

According to Global Data’s “Business of the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023,” the tournament portfolio has signed 13 of the 20 brand partners since the start of 2022. The commercial portfolio of the world cup is currently linked to 20 main sponsors, worth an estimated $307.92 million a year.

New Zealand-based software company Xero then signed on as FIFA’s second women’s football-specific top-tier partner. Budweiser, Unilever, McDonald’s, multinational IT company Globant, Australia’s Commonwealth Bank, Colombian transportation provider Inter Rapidisimo and Frito-Lay are among the 2023 World Cup’s next rung of corporate sponsors.

Then there are local partners. Those include Australian wine brand Jacob’s Creek, Team Global Express in Australia and New Zealand, BMO in North America and Cisco in the Asia-Pacific region, among others, plus FIFA-wide backers Adidas, Coca-Cola, Hyundai Motor Group and Chinese conglomerate Wanda Group.

It is impossible to compare the women’s tournament’s corporate supporters to years past given the competition’s newly independent commercial status, but the list of brands putting money and resources behind this summer’s Women’s World Cup at both the global and regional levels is extensive enough to support a claim of strong demand for the asset.

In addition to the tournament sponsors, teams and individual players can sign individual sponsorship agreements, some of which are done specifically around the World Cup. Italian fashion powerhouse Prada, for example, signed a partnership with the Chinese national team, while Mexican-American food company Siete Foods inked a deal with USWNT players Naomi Girma, Sofia Huerta and Ashley Sanchez. Australia’s Sam Kerr, the face of the host country’s Matildas, has multiple sponsorship agreements with brands including Lego, Rexona and IWC watches.

Even former USWNT stars such as Mia Hamm, Abby Wambach, Brandi Chastain, Briana Scurry and Carli Lloyd are riding the World Cup wave, enjoying a sponsorship deal from Frito-Lay.

Prize Pool and Player POV

This year’s tournament also boasts a new prize distribution model.

In response to pleas from players and FIFPRO, FIFA earmarked an unprecedented $110 million for the women’s World Cup prize pool. All told, a total of $152 million will be distributed among federations, including support funds for team preparation, prize money and payments to players’ clubs, which represent a tenfold increase from 2015 and a significant jump over 2019. A total of $40 million, including $30 million in prize money, was awarded at the last women’s tournament in France.

Perhaps more importantly, in June, FIFA announced that more than half of the designated prize money will be paid directly to the players. The decision to allocate a portion of the prize money—which has historically all been paid to federations, to then distribute among their team members as they see fit—specifically for the participating players is a first for FIFA and comes amid revelations that certain countries have failed to compensate their athletes for their World Cup participation in the past. Participating member associations will now receive a separate sum to support their operations as a federation. (There has not been much clarity from FIFA or FIFPRO, the global players’ union, about how the organizations plan to ensure the federations renumerate the specified player funds as intended).

According to the new distribution system spelled out by the organization, every player in the 32-team field will receive at least $30,000, with the amount increasing as the teams progress in the tournament. The members of the winning team will each get $270,000. That’s significant for many of the players, who, according to a report released by FIFA, make an average of $14,000 a year globally.

FIFA says its end goal is an equal prize pool for the men’s and women’s tournaments. This year’s $150 million pot, however, is equal to just a third of the $440 million paid out in Qatar last year. The global governing body is still striving for equal pay by the 2026/2027 World Cup cycle.

That said, FIFA’s total investment in the upcoming World Cup is budgeted to exceed $500 million. For the first time, teams and players participating in the women’s tournament can expect the same conditions provided during the men’s competition in Qatar—from the delegation size FIFA will sponsor to hotel accommodations to travel standards and training facilities.

Best of Sportico.com