A fatherhood in football: How Drew Ogletree and his son are chasing NFL dreams together

INDIANAPOLIS - When Drew Ogletree extends for a pass from Matt Ryan, he’ll stretch out his gangly arms and flash a tattoo that can explain everything.

It depicts an adult hand passing a crown to the hand of a baby. On the crown are the roman numerals for the date of Oct. 24, 2014.

The Colts’ sixth-round pick was a junior on the Northridge High School team in Dayton that day. He was warming up with the special teams before a game when someone rushed over to say that his girlfriend was headed into labor. She’d been due in December, but the baby was coming now.

Ogletree rushed back to the locker room and felt the tears well in his eyes.

His coach had never seen him this way before, so fragile and lacking control. Ogletree told him the baby was coming, and it might mean he’d have to miss the game.

“You’re going,” Northridge coach Bob Smith said. “This is your real family. We’re a part of it, but this is the real thing.”

More Colts news: Colts starting safety Khari Willis retiring at 26 years old to pursue ministry

He rushed through the doors of the hospital wing in time to see a screaming baby boy arrive. Andrew Ogletree Jr. was born nearly two months early, and his father got almost three minutes with him before a nurse whisked him away into intensive care.

And then his girlfriend told him to go play.

He raced back in time for the start of the second half, and though his team would lose, he'd help pitch a shutout the rest of the way by forcing a fumble. He got pats on the helmet from his teammates and cheers from his family, save for a father who never came around anymore.

Drew was in the hospital wing for 13 minutes that day, but those ticks of the clock made enough of an imprint to become his first tattoo.

“I’m handing him the crown of knowledge that I’ve learned in my life and letting him run away with whatever he learns from it," Drew said.

It's the distillation of a father's love, something he has long been able to give but never receive.

'It started to fade away'

That was seven years ago. Some days, it feels like seven decades. Others make it more like seven days.

Drew has graduated high school and college since then, played football at two universities, moved from tight end to wide receiver, survived a pandemic, reconnected with a father and then lost him again, all before being drafted in the sixth round by the Colts.

This has been Andrew Jr.’s entire life. He started as an infant sized like a football in the arms of a high school junior. He’s now the high-fiving first grader on a scooter at the back of the end zone.

“He wants to be just like me and do everything I do,” Drew said.

This is the ecstasy Drew brings to these early Colts practices, the kind that had him fist-pumping the air in his virtual news conference. He's just a rookie, only 23 years old, but he has one of the oldest kids on the team.

He is living a 7-year old’s dream, his and his son’s.

But he also lives with a 7-year old’s scars. For now, those only belong to him.

Before Drew would grow to be 6-foot-5 or run like a deer in the open field or even play tight end, his parents split. His father moved across town, and he would come to visit. As time went on, he visited less and less.

“We had a good connection,” Drew said, “and then it started to fade away.”

Drew was 7 and his brother, Aaron, was 6. He could see his mom fighting to keep his dad in their lives, at birthdays and sporting events. Drew eventually told her it was OK to let go.

“I know deep down it bothered him a lot,” Angie Hartman said. “I can only show him so much.”

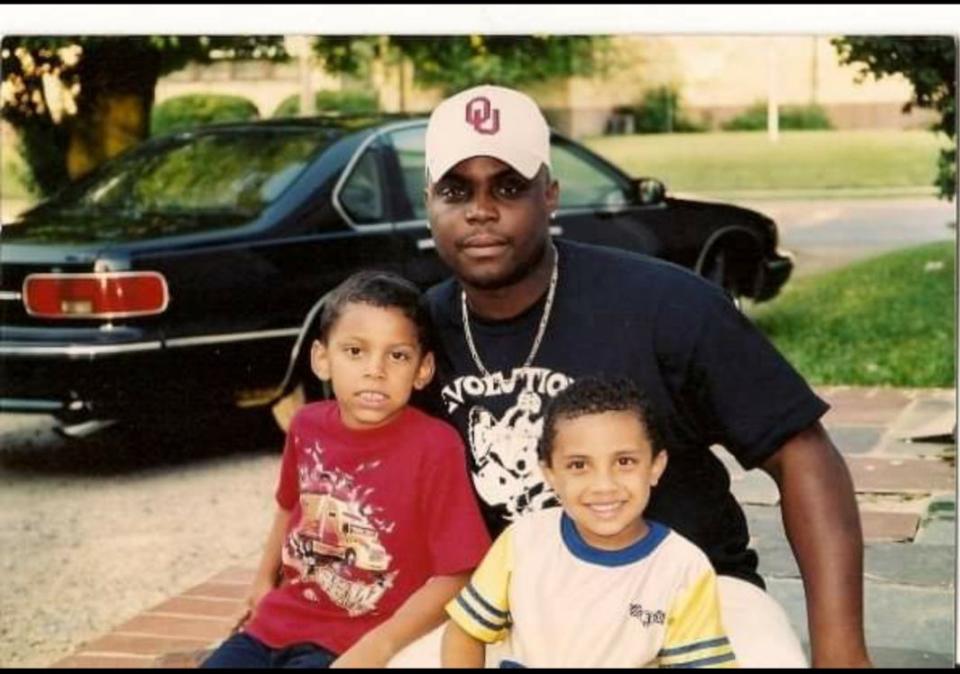

Andre Ogletree never fully disappeared from his sons’ lives. He lived 15 minutes away, driving semi trucks and laying concrete in order to fill the days. For a while, he checked in once a year, just enough to remind them he was alive.

Without him, Drew forged his way in a body that was soon a head taller than most everyone. In high school, he became an all-state football player who caught 102 passes as a senior and an even better basketball player, finishing as the Division III player of the year in Ohio.

He did it all with a newborn baby and a newborn brother. Just 10 days after Andrew Jr. entered the world, his mother gave birth to a baby named Micah.

Doyel on Matt Ryan: New Colts QB Matt Ryan can really lead a team, but I question his taste in smoothies

That limited the help he’d get from the only parent he had in his life. And eight months into Andrew Jr.’s life, he split up with his girlfriend, and they came up with a custody plan. Drew would get Andrew Jr. on the weekends. That meant he could come to his football and basketball games.

His mother had to handle both babies in those moments, all so her son could try to focus on a game and maybe land a scholarship, the one route to affording a future for this house of single parents. At nights, stress built as babies cried and woke each other up.

“We were all ready to break down,” Hartman said.

To focus on his son, to be present like his own father wasn’t, Drew stayed home in the summer rather than attending any football camps. He figured basketball would be his best path anyway, but the offers didn’t come there either.

Findlay eventually offered a half-ride, so Ogletree jumped at it. He showed up and the coaches planted him at wide receiver, since he could bench press only 225 pounds a single time.

But he could go up and snatch any pass his coaches called for him, so they’d test the limits. They instructed quarterbacks to aim for the yellow crossbar of the goal post, and Ogletree would meet the ball in the air every time.

“It was a no-brainer when he walked in at 6-5 and 185 pounds with wide shoulders,” said Troy Rothenbuhler, then Findlay’s offensive coordinator. “We watched his football clips. We watched his basketball clips. And we went, ‘Yeah, we’ve gotta get this guy.’”

Ogletree posted 787 yards and 10 touchdowns combined his first three years. Then he tore his knee.

One day while he was rehabbing, Colts scout Chad Henry approached Ogletree and told him his team liked him but only if he would make the switch to tight end.

The previous fall, Ogletree was home for Thanksgiving dinner with his family when his father showed up. The two were men now, eating at a table with people they mutually loved while Andrew Jr. raced around. The tension didn’t cut as smoothly as the turkey did.

Finally, the two went outside and had the conversation they never had before, grown man to grown man. Andre Ogletree apologized for going away and rarely coming back, for not being a father or a grandfather or even a fan at his games as his mother, aunt and grandparents always had.

When you make it to the NFL, he told him, it’ll be because of you and them, not him.

Drew told him he wanted him back in his life. His son taught him the value of fathers, after all, and he’d been waiting two decades for his. Andre agreed, and they started to meet up for dinner.

Then he disappeared for good. A pandemic took over the country, and Andre Ogtletree caught the virus and died from it. He was 49.

He never got to see his son play football games, as a knee injury wiped out the 2019 season and a virus took 2020, just before it took him. But he did get dozens of dinners with his son, conversations about college and women and of raising a growing boy. Andre told him he was proud of him, mainly for avoiding the mistakes that have consumed their lives.

“He’s not there anymore, but those are the things I cherish,” Drew said, looking back. “I dream about it sometimes.”

'He's on a mission'

Drew attacked football with a newfound adrenaline after his father passed. This wasn’t just a game anymore but also a reunion of multigenerational pain and love, those emotions swirling into kerosene in the mortar of his 6-foot-5 frame. It was there when Drew hit people, and it was written on ink on his forearm whenever he went up to snare a pass.

It’s what finally urged him to leave Findlay, the place he felt indebted to for giving him a chance when nobody else would. He had entered the transfer portal and then come back out, but the loss of the 2020 season to COVID reminded him of what else he lost, and what that man expected out of him when he was gone.

He transferred to Youngstown State, where his first Findlay offensive coordinator, Troy Rothenbuhler, had taken over as offensive coordinator. He had heard about the Colts’ urging for Ogletree to move to tight end. He bought into the idea when he saw what Ogletree had become in the two years since he found his father again.

He was 250 pounds now, or 65 heavier than when he got to college. It was the product of a diet of 12 scrambled eggs and half a pack of sausage every morning, of turning core lifts into competitions with offensive linemen.

Youngstown State was tasked with playing two football seasons in the 2021 calendar year, but Ogletree was more than ready to make up for lost time. He needed one month to be voted a captain. He showed up to film sessions and workouts and let younger players know what the standards must be.

The players called him “Pops.”

“You show up and you outwork people. Then everyone looks at you and goes, ‘This guy is here for a reason. He’s on a mission,’” Rothenbuhler said.

All the while, Drew’s son was in kindergarten, reaching the age where he understood what his dad was chasing out here. Drew had Andrew Jr. during the summers, so he’d bring him to everything, from 5:30 a.m. workouts to bonfires and squirt-gun fights. One week, the players voted him Player of the Week.

He gave his son an iPad to get through the days. When Drew would get out on the field to run his routes, he’d look up and see Andrew Jr. staring at him intently, the iPad nowhere in sight.

Andrew Jr. was starting flag football the next spring, and he wanted some moves to try out. Drew pulled one up on his phone recently of Andrew Jr. playing quarterback, where he drops back and surveys the field before scrambling left and ziplining down the sideline to the end zone.

Drew’s brother, Micah, was born 10 days after Andrew Jr., and the two mirror each other's actions when they're together. He’s in first grade, and he has the same teacher his brother did, who just happens to be the wife of the football coach. He gets the school hyped for the days when his brother comes back to talk.

“Right now, I’m getting chills just from thinking about them looking up to me,” Drew said. “They watch my every move.”

Those eyes became more daunting than the ones belonging to NFL teams, which were suddenly interested in a 6-5 tight end who managed 40 catches between two seasons in a single calendar year. But after all the years of wishing his dad would watch, the microscope became a friend, magnifying the steps he took day after day in hopes of mastering a craft.

The draft rolled around and Drew felt good about his chances, but he watched on Thursday and Friday as he didn’t get selected. His mother could tell he needed a break, so she asked him to carry a box out to her trunk.

He lifted the hatch of the silver Chevy Equinox to find Andrew Jr. lying on the floor.

His mother skipped work to fly to Maryland, then drove seven hours back with Andrew Jr. so he could be there for the draft’s final day.

The next day, the sixth round rolled around and Drew’s phone began to buzz. Colts general manager Chris Ballard was on the phone. It turns out his scout, Henry, never stopped watching Ogletree over the years. He became their target during drills at the Hula Bowl, where all that physical growth was on display.

Drew's mind was spinning by the time he started a Zoom press conference, when he was fist pumping the air.

“I’m a ball of clay,” he said into the camera. “They can mold me however they want.”

Drew’s father worked as a stonemason, filling empty plots of land with concrete so new structures could form. He molded little of his oldest son's life, but he laid more of a foundation than he ever realized: He passed him some of these genes, which now stretch 6 feet and 5 inches, amass just 4% body fat and can lift more weight than any other tight end in the NFL Draft.

Now, the body has a path to keep running on. That’s why he squeezed his mother and son tight when the phone call they'd been waiting on finally came.

In the hysteria of screams and applause, Andrew Jr. wasn't sure what was happening, how this day would shape the arc of his life. But he saw the people around him crying, so he started crying, too.

NFL salary cap 2022: Colts pay quarterback Matt Ryan the most

'I'm a great father'

This August, a father and a son will enter an NFL stadium for the first time.

It’ll be a Colts preseason game, and Drew Ogletree will be down on the field in pregame warmups. It’ll be nearly eight years since he was in the same spot and heard Andrew Jr. was about to enter the world, and he’ll peer into the stands and spot him next to his mother and his brother.

Then he’ll think of his father.

“Every pregame, I can feel that he’s watching over me, making sure I’m safe,” Drew said. “I know he’s looking down at me proud, not just because I’m a pretty good football player but because I’m a great father.

"I think that’s what he’s proud of me for.”

To make this last, to end the generational cycle of pain, he must turn his father’s mistakes into lessons. His absences must become photobook moments, the kind a grandmother drives 7 hours in secret to create.

As Andrew Jr. finishes first grade on a military base at Fort G. Meade, he isn't of age to understand the depths of multigenerational pain, but soon he will be. In these eyes, a grandfather can still be anything. He can be an ancestor or a ghost, depending on what gets passed in the crown.

Day by day, Andre Ogletree is becoming more of the former for Drew. Their two years together again illustrated how time is fleeting, much like the football life Drew keeps chasing with his son.

So he'll point to a boy in the stands before a game, long enough for that boy to squirm in his seat and exclaim to the crowd, "That's my dad out there!"

The moment will last a few minutes. It will be all the time in the world.

Contact Colts insider Nate Atkins at natkins@indystar.com. Follow him on Twitter @NateAtkins_.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Colts: Drew Ogletree has 3 generations to represent on Father's Day