The Ego-Driven Behavior That Almost Killed Me

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Rifle Mountain Park, Colorado, is not really known as a dangerous climbing area. There have been accidents, yes, but almost always due to preventable belayer/climber error. And so far, zero climbing fatalities. This is remarkable when you consider how many easily distracted, beta-spraying, self-involved narcissists (myself included) have climbed here over the past 30-plus years, how many clips routinely get skipped on redpoints, and how downright horrible the rock can be. I mean, shit, a massive chunk of the Arsenal simply gave up and fell off one spring night in the 1990s, bolts, chalked holds, fixed draws, and all--helped along, one might imagine, by climbers shoehorning sticky-rubber knees inside places no self-respecting chosspile should ever countenance.

And yet, there is one route in Rifle that actively tried to kill me back in the early 1990s.

But it's not in the way you might think.

***

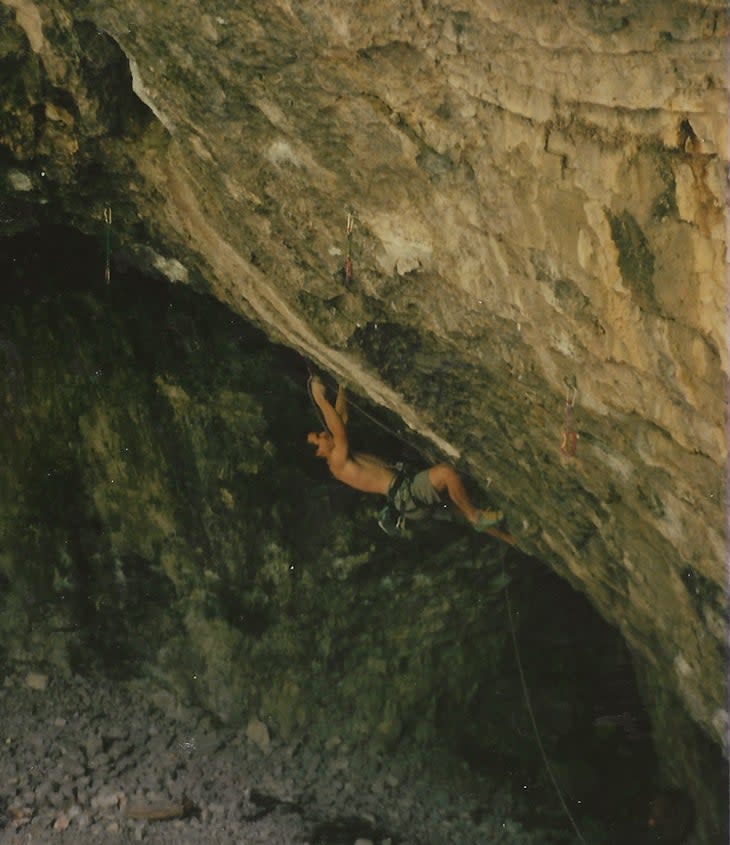

The killer climb in question was Dumpster BBQ, a 30-foot 5.13d in the diminutive Crystal Cave, about midway along the three-mile canyon. Here, up a short, steep, nasty talus-and-dirt embankment, a small, scooped-out grotto offers panels/pillars of brilliant blue and gray rock framing friable hollows of Rifle's infamous white, pastry-flake limestone. A thick webbing of trees blocks the cave's entrance, so it's all but invisible as you drive by.

In summer 1992, my friends Scott Leonard and Ryan Sappenfield (aka "Sapper," the namesake of the popular Sapper Cave up-canyon) bolted a six-bolt line out the cave's middle pillar, tracing a bicepian symphony of underclings, sidepulls, and tiny crimps on which they could do most--but not all--of the moves. They recruited me that autumn, and when I unlocked the route's two crux sequences in isolation, I began trying to redpoint it. Because the climb was so bouldery, we'd warm up in an eliminate bouldering cave across the road at the Bauhaus Wall, soaking up morning sun then heading into the crisp autumn shade.

This was the 1990s, and anorexia/eating disorders among performance-focused climbers were rampant--possibly more prevalent than now, but with the unhealthy twist that we actively encouraged each other to be rail-thin instead of having any sort of real discussions about our behavior. We'd all climb with our shirts off and comment on how "honed" so-and-so was looking. I was so proud of myself, during my anorexic freshman year at college, when my friends started calling me "Auschwitz Boy" for all my ribs poking through my skin, that I never stopped to consider just how unhealthy I'd become. The culture was just in the air. I remember one friend recounting how a visiting German climber, at Smith Rock, showed him how to sneak off into the bushes and make himself throw up after he (the German) had binged an entire package of lemon-creme cookies in one sitting. There were also stories of another European climber taping glucose pills to a resting hold on Churning in the Wake (5.13a) at Smith so they could top up their blood sugar, depleted by dieting, en route to the chains. And so on....

Meanwhile, there was almost zero sports-science research on climbers. Training wisdom was crap--we had elbow-tendonitis-inducing Bachar Ladders, free weights, squeezy rubber doughnuts, and hangboards with bungee cords to take weight off but that instead snapped back and nailed you in the crotch, possibly sterilizing you. Thus, the quickest way to tweak the strength-to-weight ratio was to starve, which many of us--myself included--were a little too good at. There was minimal community awareness of the deleterious long-term effects of disordered eating on physical and mental health, which, for many of us, led to big-time consequences.

That autumn, 1992, in order to shrink quads that had ballooned up after a summer mostly spent mountain biking, I began to eat as minimally and as fat-free as possible, trying to drop weight for Dumpster BBQ. One item on the menu was plain rice cakes with salsa, which were low in calories and made you feel temporarily full. (We'd also eat rice cakes with mustard, to similar effect.) Either Scott or I always had a big, family-sized jug of Pace Picante Sauce and a sleeve of rice cakes close at hand.

In October 1992, we drove out to Rifle one Friday evening after class at the University of Colorado Boulder, pitched our tents in the "Ghetto Meadow"--our un-PC nickname (hey, it was the 1990s) for the big, grassy group campsite--shoveled down our rice cakes and salsa, and went to bed. Because we were cheap college kids, we didn't buy ice for the Igloo cooler holding our perishables, including the salsa. It seemed "cold enough" that the food wouldn't spoil, though I do remember that night's feast tasting acidic and funky.

The next morning, Scott crawled out of his tent, threw up on the sad, muddy grass of the Ghetto Meadow, looked over at me slithering out of my own tent, and said, "Dude, I don't feel good."

"No shit," I said. "Can you climb?"

"Not sure. But I think I can still belay."

"OK."

We warmed up at Bauhaus Wall, but by the time we'd crossed the road to the Crystal Cave, I felt nauseous, too. After I gave one jellyfish-armed, halfhearted burn on Dumpster BBQ, we headed home. The four-hour drive back to Boulder along I-70 felt endless. As Scott languished in the seat next to me groaning and clutching his belly, I grew increasingly febrile, my body spasming and threatening to let loose at both ends, kept in check only through sheer willpower and an abhorrence of gas-station bathrooms.

Back at the off-campus condo Scott and I shared with another roommate, we stumbled inside and Scott went to his bedroom. It was then that I almost died--on the toilet, which I'd been holding off on using for hours. As hot, horrible effluent sprayed out of my backside--the bulk of my body's free water, it seemed--my vision went dark and I began to lose consciousness. I somehow cleaned myself up, stumbled out to the living room, moaned "Help," and fell to the floor, blind, poleaxed, sweaty, and terrified. Scott, just on the edge of falling asleep, heard the thud, came out, saw my sorry state, propped me up in a chair and got me a glass of water, and called 911. One ambulance ride and six one-liter bags of IV fluid later, I was back among the living.

It was close. Food-poisoning-caused dehydration and overall depletion from self-starvation had made me so weak that I went into shock, and my blood pressure began to plummet and my heart rate to slow alarmingly in the ambulance. (My vision had come back online after the EMTs laid me flat on my back in the condo.)

"This kid's not going to make it," was the subtext of a shared glance between the two EMTs as we sped toward Boulder Community Hospital, sirens blaring.

But somehow, I did.

***

I'd like to say I learned my lesson, but the truth is I kept starving myself for months afterward. And while I did eventually redpoint Dumpster BBQ, soon thereafter I began having panic attacks, probably due to depriving my brain and nervous system of the fats you need to synthesize neurotransmitters. Then my weight climbed back up anyway when my body had had enough of the chronic calorie deficit and began compelling me to eat--a lot. It's a lesson many climbers focused on sending their hardest or on competition climbing eventually learn: the short-term gains you get from using disordered eating to stay light are more than canceled by long-term damage to the brain and body, including the risk of physical complications like cardiac arrhythmias that can literally kill you.

In any case, a year or two later, I was able to repay Scott for his intervention in calling 911 that fateful day. Scott and I were out at Rifle early spring 1993 on a bright, clear day, doing laps to build pre-season fitness. We were, as far as I could tell, the only climbers--or people, period--in the canyon. At day's end, we straggled into the Nappy Dugout cave next to the Wasteland so that Scott could point out the beta on a route he'd bolted there, Fringe Dweller (5.13a), which climbed a funky gray pillar on the edge of the cave. As I stood there surveying it, Scott walked over to what would become Lungfish (5.14b), after Jeff Webb redpointed and named it in 1994. Munching on a bag of stale, crumbled tortilla chips, he began looking up at the climb's miniscule holds, trying to picture a sequence. (The Boulder climber Chris Hill had bolted Lungfish in fall 1991. It was the first route in the cave proper, which we'd originally named the "Shit Cave," since everyone climbing at the Wasteland would go there to relieve themselves--porta potties had yet to be installed in the lower canyon.)

It was precisely then that Scott began to choke, the chip crumbs forming a soggy plug in his throat, the angle of his neck as he looked up at the wall having made it difficult to swallow. He gestured to me, wild-eyed, making the universal sign of choking. I ran over, got behind Scott, and began to furiously administer the Heimlich maneuver, balling my right hand into a fist and thrusting it up and against Scott's abdomen with my left palm. Ten seconds later, Scott spat a massive ball of chewed-up chips onto the ground.

"Holy shit, dude, thanks for saving my life!" Scott coughed.

"Of course, man," I said, my voice shaky with adrenaline. "And besides, I owed you one for calling 911 that day for me."

And it was true: If Scott hadn't called the ambulance back in 1992 and had just fallen asleep instead, I probably would have died. And Scott, well, he had maybe ten minutes tops without air before irrevocable brain death. And if I hadn't saved him, there was no one else around to help. It had been a fair trade, and we'd each saved the other's life.

As for Dumpster BBQ and Lungfish, to my knowledge they have not claimed any other victims, though you never know. I've heard of more than a few bruised egos caused by each climb, and even some climbers who essentially retired from the sport after failing to complete one route or the other. Which, for someone like me who's totally obsessed with rock climbing--to such a degree that, as a young man, I was even willing to compromise my health for it--could in fact be a "fate worse than death."

Matt Samet is a freelance writer and editor based in Boulder, Colorado, and the author of the memoir Death Grip.

Also Read

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.