Colorado’s Big 12 Leap May Create Super Conferences … and Legal Issues

The University of Colorado’s decision to leave the Pac-12 for the Big 12 after the 2023-24 season could rattle the business and law of college sports.

Colorado’s move comes only a year after USC and UCLA revealed they’ll be leaving the Pac-12 for the Big Ten in 2024.

More from Sportico.com

Volunteer Coaches Antitrust Case Survives NCAA Motion to Dismiss

New NIL Bill Pushes Athletes' Rights, Including Group Licensing

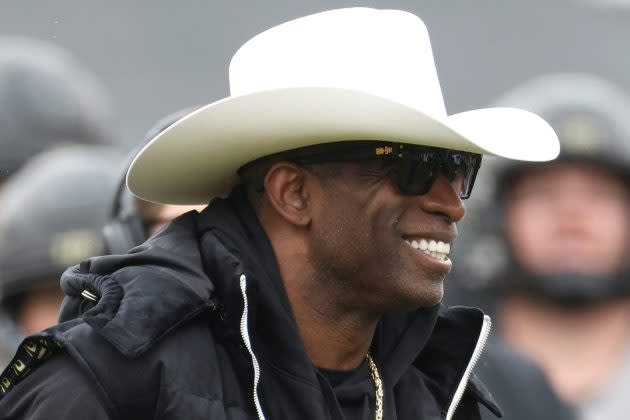

Losing Colorado, now led by Pro Football Hall of Famer Deion Sanders, along with two storied programs in USC and UCLA, downgrades the Pac-12—at least in the short term.

The conference is expected to seek replacements, with San Diego State, SMU, Fresno State, Boise State and UNLV possible targets. But whether and when those schools, which are under contract to other conferences and are subject to potential exit fees, can be persuaded to join is unclear.

As if his conference’s dwindling roster isn’t causing enough headaches, Pac-12 commissioner George Kliavkoff also faces expiring media rights deals next year. There are no new deals in place yet.

The Pac-12 is unlikely to go out of business anytime soon, but it may struggle to maintain its status as part of the Power Five, which could in turn could impede negotiations with potential media and broadcast partners. On top of that, the Big 12 reportedly wants to expand from 13 to 14 schools, and is said to be zeroing in on the Pac-12’s Arizona. According to reports, the Big Ten has eyes for Oregon and Washington.

The 69 member schools of the Power Five conferences share their elite status largely because they generate similarly massive revenues. But if one of the five conferences falls behind the others, that conference and its remaining members could lose their coveted perch.

If another round of realignment follows, the theoretical Power Four could become a Super Power Two, with the SEC and Big Ten gobbling up top markets coast-to-coast and leaving a second tier of conferences in their wake.

No one has a crystal ball, but there’s a legal hook worth watching.

In NCAA v. Alston (2021), Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that when NCAA members agreed not to pay athletes for academic-related expenses, it constituted price-fixing. He explained the NCAA and its members are subject to ordinary antitrust scrutiny, and that setting a price at $0 is illegal—especially, Gorsuch underscored, “in a market where the defendants exercise monopoly control.”

Less noted, Gorsuch stressed that an individual conference, through its members, can adopt amateurism rules as the conference sees fit—they just can’t all do it en masse.

Gorsuch literally wrote Alston “applies only to the NCAA and multiconference agreements.” He further emphasized “individual conferences remain free to reimpose every single enjoined restraint tomorrow—or more restrictive ones still.”

Gorsuch’s underlying logic was straightforward. When the NCAA and its roughly 1,200 members act to restrain competition in some way, the impact on college sports is national and often profound. When one conference and its dozen or so members do the same, the impact is far more limited. Other conferences, after all, could decide the same issue differently.

The Ivy League has relied on Alston as a defense against an antitrust lawsuit, Choh et al. v. Brown University et al., centered on the conference’s prohibition of athletic scholarships. Along with its member schools, the Ivy League is accused of unlawfully conspiring to not pay athletes “any compensation” in exchange for their athletic services.

Last Thursday, Ivy League attorneys filed a brief in which they emphasized how Gorsuch wrote “individual conferences remain free” to impose “more restrictive” restraints on competition. “The rule challenged in Alston,” they added, “applied across the entire NCAA, preventing student-athletes nationwide from receiving that compensation [whereas] the Ivy League Agreement governs just a single, eight-school conference.”

But if conference realignment brings about super conferences that resemble the NCAA in terms of controlling college sports or at least a sizable portion of it, Gorsuch’s distinction between the NCAA and a conference could collapse—and with it the judicial deference conferences currently enjoy.

The potential consequences are far-reaching. Power Five conferences could eventually adopt rules recognizing college athletes as employees, while smaller conferences might stick to the student-athlete model. Some conferences might also explore revenue sharing with athletes or different rules for NIL. The degree to which a conference is confident its actions would withstand judicial scrutiny would shape that conference’s willingness to innovate.

So while Colorado dropping the Pac-12 is understandably generating headlines, an even more compelling story might have to wait for a future court ruling.