Bloody Monday: Why some say people are forgetting one of Louisville's darkest days

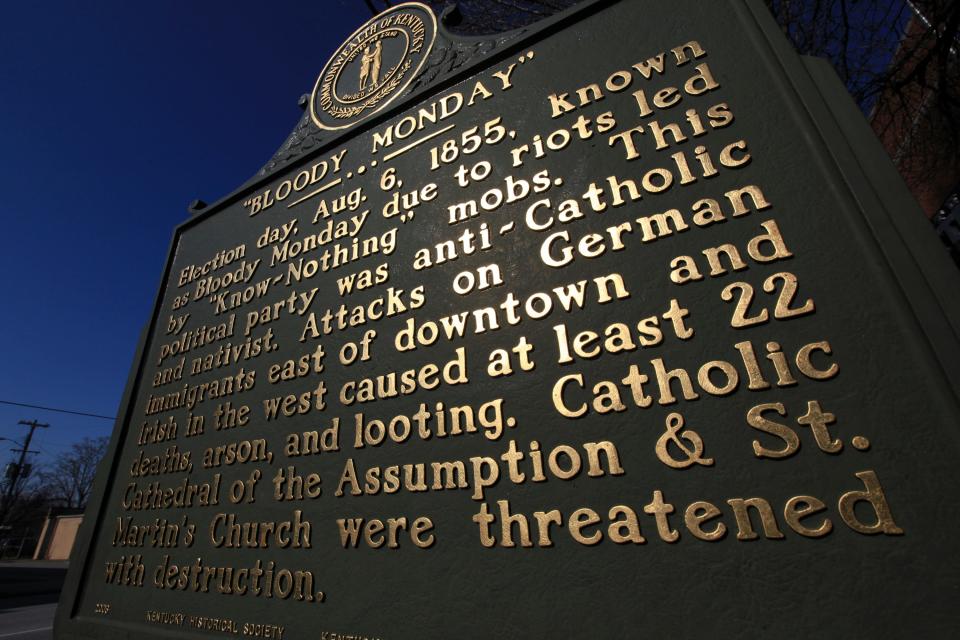

On August 6, 1855, Louisville was the stage of one of the worst sets of anti-immigrant riots in American history.

On that day history would ultimately call “Bloody Monday,” German and Irish Catholic immigrants who had come to the city to start new lives and exercise their rights as American citizens were instead beaten, stabbed and shot in the streets.

More than 20 people were killed that day amid the fighting, that was instigated by the Know Nothing Party, a Protestant political group that feared the waves of foreigners coming into the country were a threat to American democracy.

Nearly 170 years later, historical experts say the city has come a long way. Louisville is now considered one of the most welcoming cities in America for immigrants and boasts a diverse Catholic community.

Catholic Charities of Louisville CEO Lisa DeJaco Crutcher, whose immigrant ancestors had already settled in the city by that time, said, however, the infamous day — and the sentiments behind it — are events that some in the area seem to have forgotten.

"I would like for more people to know about and reflect on our history," she said. "I think we do a pretty good job as a community, but sometimes … people with a heritage like mine don't always draw the connection. I wish that more people consciously thought about that."

State news:President Biden to visit flood-ravaged Eastern Kentucky

Anti-immigrant sentiment ignited by fiery rhetoric

During the 19th century, immigration in the United States saw a dramatic surge. Historians estimate that between 1800 and 1930, more than 4 million foreigners, especially those of Irish and German descent, emigrated toward American soil.

In the 1840s and 1850s alone, experts believe roughly 1.5 million new residents came to America. In Louisville, nearly a quarter of the city’s 43,000 residents were foreign-born as of 1855, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville.

As more immigrants kept coming to make a home in Derby City, anti-immigrant sentiment mounted, mirroring what was seen around the nation.

"The entire United States was sort of afflicted by this anti-immigrant fervor," DeJaco Crutcher said.

Local crime:After murders and assaults, city orders troubled gas station to vacate property

Tensions in the city were stoked by the Know Nothing party, which were also spurred to action by their party leaders and the inflammatory words written by Louisville Daily Journal founder and longtime editor George D. Prentice. Members of the party deployed to precincts around the city on Election Day, preventing hundreds of German and Irish Catholic immigrants from exercising their right to vote.

As the day went on, violence erupted. People were beaten and stabbed in the streets. In one of the worst incidents recounted in the Aug. 7, 1855 edition of the Louisville Daily Journal, an entire immigrant neighborhood was set on fire, its residents were shot as they tried to escape their burning homes.

At least 22 people died on that day, though some historians believe the death toll was much higher.

Historians argue that Prentice, using his influence to publish anti-immigrant rhetoric in what was, at the time, the largest newspaper in the Ohio River Valley, played the largest part in inciting the riots that day. Others argue Prentice's role was minor and tensions were already poised to boil over due to political conditions in the city at the time.

Regardless, where Prentice was once celebrated, the city has since changed course in recognizing his legacy. Following a series of public conversations, a statue in his likeness that stood outside the main branch of the Louisville Free Public Library in downtown Louisville was removed in 2018.

“Mr. Prentice used his position as founder and long-time editor of the Louisville Journal to advocate an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant message that led to the 1855 Bloody Monday riot where at least 22 people were killed,” Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer said at the time. “His statue is especially inappropriate outside the library, a place that encourages education, inclusiveness and compassion.”

From flashpoint to progress

Over the course of the next century, however, anti-immigrant demonstrations faded from the public eye and the sentiment in Louisville shifted with the times.

Dr. Tom Owen, an archivist and historian at the University of Louisville and a former Louisville city councilman, said that by the 1950s and 60s, Louisville was perceived as "a national center of ecumenism," a principle that promotes unity among Christian churches in the world.

"Those people that were perceived as pariahs by the dominant Protestant majority in the 1850s … got assimilated pretty thoroughly,” he said. “They integrated, they married and were absorbed into the white privileged."

Louisville’s shift into welcoming people of all nations and walks of life has only continued since.

Jessica Wethington, communications director for the city of Louisville mayor’s office, said the city’s foreign-born population has increased nearly 40% over the past decade.

In 2018, Louisville was declared a “Certified Welcoming City” by Welcoming America, a national nonprofit focusing on immigrant support and economic inclusivity, the first city in the South to receive the designation.

Few area schools, universities offer lessons on Bloody Monday

Why this particular event in Louisville's history is overlooked is debatable. Owens suggests the phenomenon may be attributed to the generational gap between older and younger residents.

"Would a 27-year-old with a strong presence on social media be talking about 'Bloody Monday'? Probably not," he said. "But if you're of Irish and German descent and of Catholic faith between the ages of 65-72, you probably have had this discussion before."

Former University of Louisville professor Bob Ullrich, co-author of "Germans in Louisville," said he was disappointed that the event isn't commonly taught in area schools. He and his wife, Vicki, both descendants of German immigrants, feel that if it were taught, more young people would speak about the incident and learn from it.

"You would be hard pressed to find a course on Kentucky history even on a collegiate level," Bob said. "Children, their parents, and their grandparents don't know about (Bloody Monday). Nobody bothers to know about it."

Vicky said she believes there's a lot to gain simply by having conversations about "Bloody Monday."

"People should understand that anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia is what caused 'Bloody Monday,'" Vicky said. "If people aren't educated on their past, history is doomed to repeat itself. You can't pass down information that you don't possess."

Correction: This story has been edited to reflect the correct year when the George D. Prentice statue was removed by the city of Louisville.

Fancy Farm 2022:How to follow along with this year's picnic

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Bloody Monday: Some experts say memory of Louisville event is fading