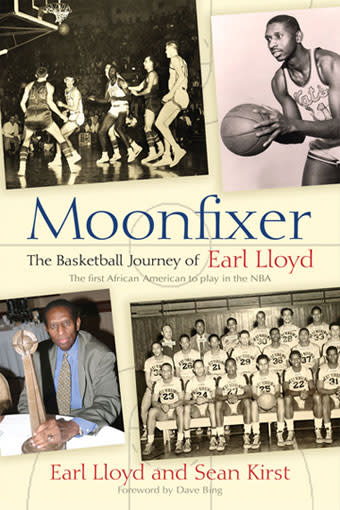

BDL Review: 'Moonfixer: The Basketball Journey of Earl Lloyd'

BDL Book Review is a new feature in which our main man Devine — an honest-to-God journalist most days, a fibbing-to-Shamgod blogger others — reviews, well, basketball books. This week: Sean Kirst's "Moonfixer: The Basketball Journey of Earl Lloyd."

There's an interesting duality to Earl Lloyd as an autobiographer.

On one hand, the Alexandria, Va., native makes for a perfect subject: Raised in what he calls "the cradle of segregation," Lloyd became the first African American to play in an NBA game (for the Washington Capitols on Oct. 31, 1950, against the Rochester Royals) — not to mention the first black starter on an NBA championship squad (the 1954-55 Syracuse Nationals), the first black assistant coach in league history, and one of its first black head coaches. He certainly has a hell of a story to tell, a tale of struggle and triumph set against the sociopolitical turmoil of mid-20th century America.

And as a bonus (from a marketing perspective, at least), while Lloyd is one of the symbolically transformative figures in popular sports culture, the details of his breakthrough remain largely unknown to fans, perhaps because he averaged a relatively pedestrian 8.4 points and 6.4 rebounds per game over his nine-year career.

As Sean Kirst, the Syracuse, N.Y., Post-Standard columnist whose conversations with Lloyd make up the bulk of "Moonfixer," notes in the book's preface: "Even during his peak years, little was made of [Lloyd's] groundbreaking status in basketball history. Despite the attention paid to racial pioneers in other sports, reporters in the 1950s rarely wrote or spoke about Lloyd's extraordinary role in the game ..." It wasn't until the 1990s, Kirst says, that more people started paying attention, starting a swell of recognition that would culminate in Lloyd's 2003 enshrinement in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

On the flipside, though, Lloyd often appears reluctant to discuss his "groundbreaking status" and "extraordinary role." In fact, he seems pretty much dead-set on undercutting it every chance he gets.

Demurring in the face of praise from folks like Kirst, Golden State Warriors executive Al Attles and Hall of Famer/Detroit Mayor Dave Bing, Lloyd repeatedly emphasizes in "Moonfixer" that he "was no Jackie Robinson" and "no Joe Louis." He makes sure to note that his landmark moment was "in many ways a function of the calendar," and that the distinction could just as easily have gone to fellow barrier-breakers Chuck Cooper (the first African American drafted by an NBA team, selected seven rounds before Lloyd in 1950) or Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton (the first African American to sign an NBA contract), both of whom saw their first game action less than a week after Lloyd debuted.

In the second sentence of the book's first chapter, he even scuffs up the historic night itself: "Almost 60 years ago, I walked out onto the basketball court in Rochester for a game I don't even remember all that well."

The tug of war between the book's apparent topic (this is a story that must be told about an important man whose contributions are too often overlooked), and Lloyd's own self-estimation (come on, don't put me on a pedestal, it's not about me) makes "Moonfixer" a challenging, sometimes even frustrating read. But the more you learn about Lloyd's character, the more his reticence resonates. His refusal to accept credit for breaking pro basketball's color barrier is grounded not in stubbornness, but rather in an inspiring worldview marked by humility and a desire to sublimate himself so that he can celebrate others. His passion burns in Chapter 6, during a discussion of the start of his NBA career:

"You don't think I remember every guy who came before me, every guy who could play the game and never got the chance in the NBA? We're doing this book because I was blessed in that way, and we're doing it to make sure no one forgets just how many people like me deserved the same break and didn't get it."

The desire shines when Lloyd talks about what kind of player he was, what he loved — and still loves — about the game. Describing one play that he started with a defensive rebound and outlet pass, then finished by filling the lane for a layup, Lloyd says, "The beauty of it, for me, isn't in the play itself. It's in the hustle, the fundamentals."

That attitude made Lloyd a great fit with the Nationals and a key contributor to their 1954-55 title team. After the Capitols folded while Lloyd was serving in the U.S. Army, his rights were claimed by Syracuse. Nats management saw the 6'6" power forward as a rebounder and defensive stopper that could take tough assignments away from Dolph Schayes, freeing up the dangerous scorer to reserve his energy for the offensive end. That often meant checking future Hall of Famers like George Mikan and Elgin Baylor ("... it's not easy going to sleep when you know Elgin's coming," Lloyd recalls).

Lloyd had been "a little more of a scorer" at historically black West Virginia State College, where he'd led the Yellow Jackets to an undefeated 1947-48 season on the way to being named the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association's Player of the Decade for the 1940s. (It's also where he got the nickname that serves as the book's title. As Lloyd tells it, the West Virginia State seniors gave all freshmen jobs, usually something impossible or close to it, as a way of messing with them. Because he was the tallest freshman, Lloyd says, "my job was to reach up and make sure the moon was shining when [the seniors] were with their girls. That was my job, and they expected me to come through. They made me the 'Moonfixer,' and it stuck.")

But despite his scoring background, Lloyd didn't bristle at his changed role; instead, he tailored his game to the "things that people watching the game from the stands won't necessarily appreciate," like face-guarding taller, better rebounders and establishing position to keep them off the glass.

"If I looked at the stats the next day, and I saw a guy only had two or three rebounds, that was my twenty points. You understand?" Lloyd says. "I don't know if you get remembered for that, but if you ask, that's how I want to be remembered. I don't call it a sacrifice because it was my job." (Later, he adds, "The kids today, I don't know if they recognize the importance of that kind of job.")

Lloyd talks about "the kids today," especially black kids today, a lot in "Moonfixer" — about the challenges they face, about under-resourced schools, about the social equality he fears will elude them. Lloyd's story is bracketed by his reflections on the election of Barack Obama, and features frequent references to "the ruling gentry" who enforced Jim Crow in his day (and, he argues, perhaps a subtler brand of segregation today). In a note to readers before the first chapter, Kirst writes, "Earl has plenty to offer about basketball, but this is hardly a basketball book. It is a testament. ... In speaking to American truths as he sees them, he is simply asking us to step back and think."

Whether or not you agree with Lloyd's opinions, the passion with which he relates them, combined with his firsthand accounts of social change during the NBA's infancy, make "Moonfixer" a compelling read capable of both shaking you up and reaffirming your love of what he calls "a game where the ball knows no prejudice; everybody touches it, and everybody touches each other."

You can reach Devine at devineboston@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter.