How the birth and death of the NASL changed soccer in America forever

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the North American Soccer League’s foundation. The competition’s influence can still be seen today

The NASL was American soccer’s big bang, the league that ignited a soccer boom in the States and brought over to American shores some of the greatest players of their generation. Former players, coaches and officials will congregate in Frisco, Texas, this weekend to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the league’s birth.

“The league was so important in growing the game on this continent that it needs to be remembered. There will be lot of memories shared,” says former Dallas Tornado midfielder-defender Bobby Moffat, a member of the 1971 NASL championship side.

On one hand, the league laid the foundations for soccer in America – foundations that helped lead to the country hosting the 1994 World Cup and the set-up of MLS. On the other, NASL lasted less that 20 years, fizzling out in 1984. Some observers have called it a failure. Former New York Cosmos president Clive Toye, who signed Pele in 1975, bristles at that suggestion.

“What people too easily overlook was that the NASL’s mission was to build the game and then at the end of it, make some money for the owners,” he told the Guardian. “The NASL as a crusader was a magnificent success. As a business, it eventually failed as a single entity. But, what it left behind is a knowledge of the game that didn’t even existed in this country before and enthusiasm for the game which never existed before.”

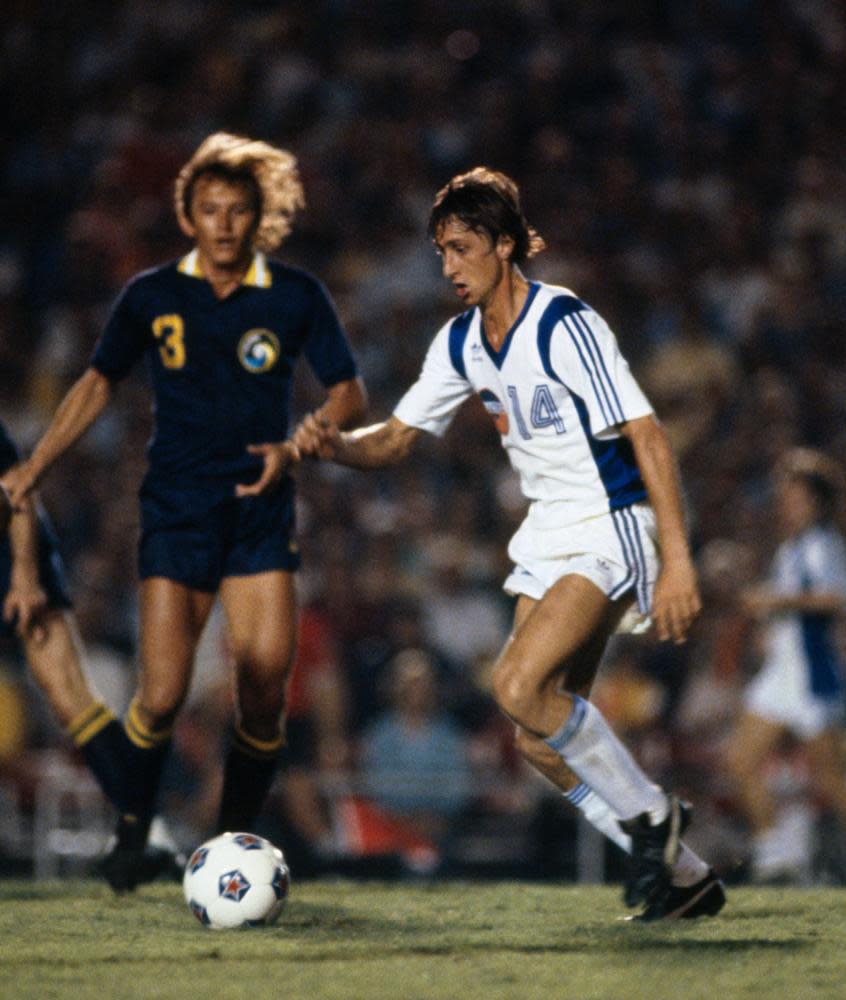

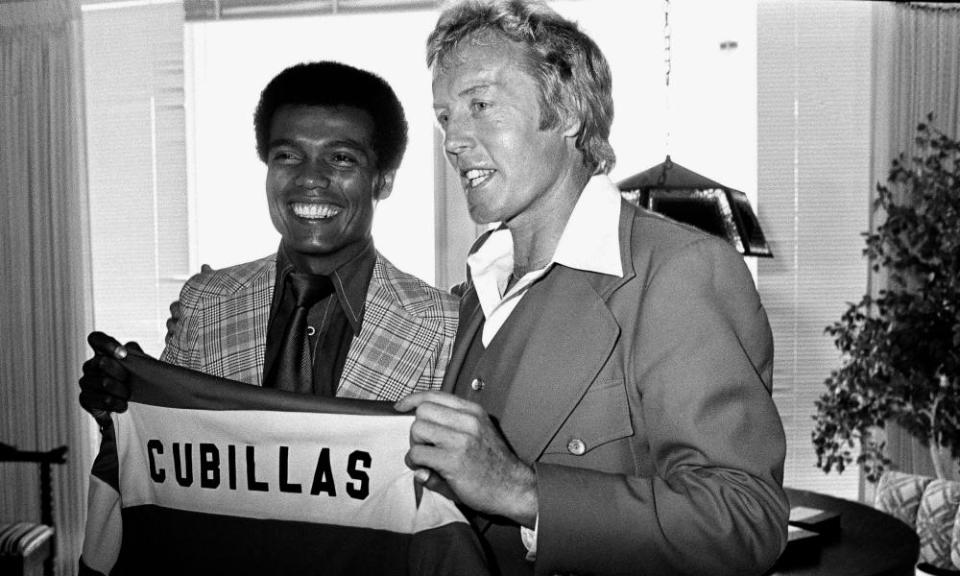

It seemed that every player worth his salt from Europe and South America wound up playing in the NASL. Pele, Franz Beckenbauer, Carlos Alberto, Johan Cruyff, Eusebio, Gerd Müller, Geoff Hurst, Bobby Moore and Giorgio Chinaglia are just some of the names who played in the league. But in the early days, before the influx of those superstars, the league’s heart was in the right place, even if the games weren’t. Many teams called baseball stadiums home, making for some challenging situations for everyone, especially goalkeepers, who had to deal with a dirt infield in front of the net.

“It made it very challenging especially when you had the dirt surface and the grass next to it,” said Dick Howard, a goalkeeper who emigrated from England to pursue a soccer career (he was there at the league’s birth and death). “The quality of the playing surfaces pale in comparison to what they are today. It was great from my standpoint because I enjoy watching baseball games and to play at Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park was great.”

Howard was one of the many players who took on missionary roles, spreading the gospel of the sport. As Rochester’s director of youth development, Howard assigned teammates to visit schools to hold clinics. That could be a challenge, when soccer was foreign to many American kids.

“I went with my bag of soccer balls on my own and they directed me to the gymnasium,” he recalls. “I heard this rumble. The rumble was students hurtling down the corridor and into the gym for phys ed. They saw the soccer balls, started dribbling, shooting baskets and said, ‘Is this a new game that you devised?’ They eventually played some sort of soccer.”

Eventually, the league stabilized and grew. A New York team – the Cosmos – was added in 1971. In 1975, the team added a certain three-time World Cup champion. Pele’s signing with the Cosmos put the league into another orbit in terms of recognition. It also helped turn the Cosmos into a team of all-stars, setting attendance records at Giants Stadium.

In many ways, the NASL was the wild west of professional soccer. Each team had personality, character and characters. For example, the coach of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, Ron Newman, was also a brilliant salesman. During a losing streak in 1978, he was brought onto the Lockhart Stadium field in a coffin, sprang out and ran to a microphone and shouted: “We’re not dead yet!” The crowd went wild.

The games themselves could be odd. The Rochester Lancers took on the Dallas Tornado in the 1971 playoffs but the lack of a penalty shootout meant the game lasted 176 minutes. The contest finally ended with a 2-1 win for the Lancers just before midnight, with the players understandably exhausted.

And while stars such as Pele and Cruyff earned plenty, many players were in it for the love of the game, rather than money. Toronto Metros-Croatia, the 1976 NASL champions, had their fans pass the hat around in a church basement to pay for players’ salaries. The team lasted just three years. The most Howard earned in a season was $3,000 with Detroit in 1968 (around $21,000 in today’s terms).

“Money was immaterial,” he said. “We just had the opportunity to play the game we loved sometimes in front of good crowds, sometimes in front of wives and girlfriends, family. We certainly didn’t enrich our bank accounts so thankfully now players are getting paid what they deserve to get paid for. You had to have that love, that passion for the game.”

After Pele’s arrival, teams wanted their own superstars. Some were worth their weight in gold, others were such poor investments that teams may as well have thrown cash out the window. “Pele had come and now there was all of this excitement and people had to get players and they overpaid for them,” says Ted Howard, who was the NASL executive director for 14 years.

As Pele played in his final season in 1977, plans were made to add six expansion teams for 1978, which swelled the league from 18 to 24 teams.

“We had a league meeting and a group of us decided we had to get rid of six to those 18 [clubs] because they were rubbish and we were better to progress with the 12 decent ones, which included people like [Chicago owner] Lee Stern and Lamar Hunt,” Toye says. “We went to a meeting. The New York mob … and some of the idiots said: ‘We must expand and not diminish, and we must add them, them, them, them’ because we had people applying willing to pay $2m a franchise. That was the beginning of the decline of the NASL as an entity.”

After the 1980 season, three teams dropped out. In 1981, seven teams folded. Warner Communications, which owned the Cosmos, lost millions because of its failed Atari video games. The organization cut back on entities that weren’t making money, including the Cosmos. The league shut down after the 1984 season.

Dick Howard, who went on to become a respected Concacaf and Fifa coaching instructor, was the Toronto TV commentator for the final NASL game, the second leg of the 1984 Soccer Bowl between victorious Chicago and Toronto. “It’s sad because I had seen the potential, the glory years of the league, and then the demise,” he says.

American soccer went through its version of the dark ages until MLS kicked off in 1996. But the lessons learned from the NASL helped build the game in the long run. Not wanting to repeat past mistakes, the league’s architects formed a single entity, so teams would not throw away huge sums of money, thanks to a salary cap. After playing in NFL stadiums and venues that were too big to produce an intimate setting, teams started to build soccer-specific stadiums. Instead of practicing at schools or parks, every club has its own first-class training center.

Then there’s the general acceptance of soccer in America. Back in the day, the best way for a doubting media and the American public to criticize the beautiful game was to go ugly. The insults grew familiar: it was a Communist sport; the players had unpronounceable names; only immigrants played; people went into soccer because they couldn’t cut it in American football or baseball.

Today, in contrast, criticism is about issues that matter: why the US Soccer Federation is taking so long to name a men’s national coach; the Columbus Crew crisis; and how the US women’s team are trying to keep a step ahead of their opponents.

“It just gives you enormous pride to know that all those hours that you put in and trying to do something comes to fruition,” says Ted Howard.

You don’t have to go to a stadium to see the NASL’s impact. Recently, Toye watched his doctor’s 11-year-old daughter play near his south Florida home. He was astounded by the sophistication of players so young.

“It was wonderful to watch, the way they were playing, the way they did with such composure, with such complete professionalism and at that age,” he says. “Boy, oh boy, it was worth it after all.”