The tough break that enabled Drew Brees' rise to stardom

The man who’s poised to break the NFL’s all-time passing record Monday night wasn’t always on a path to superstardom.

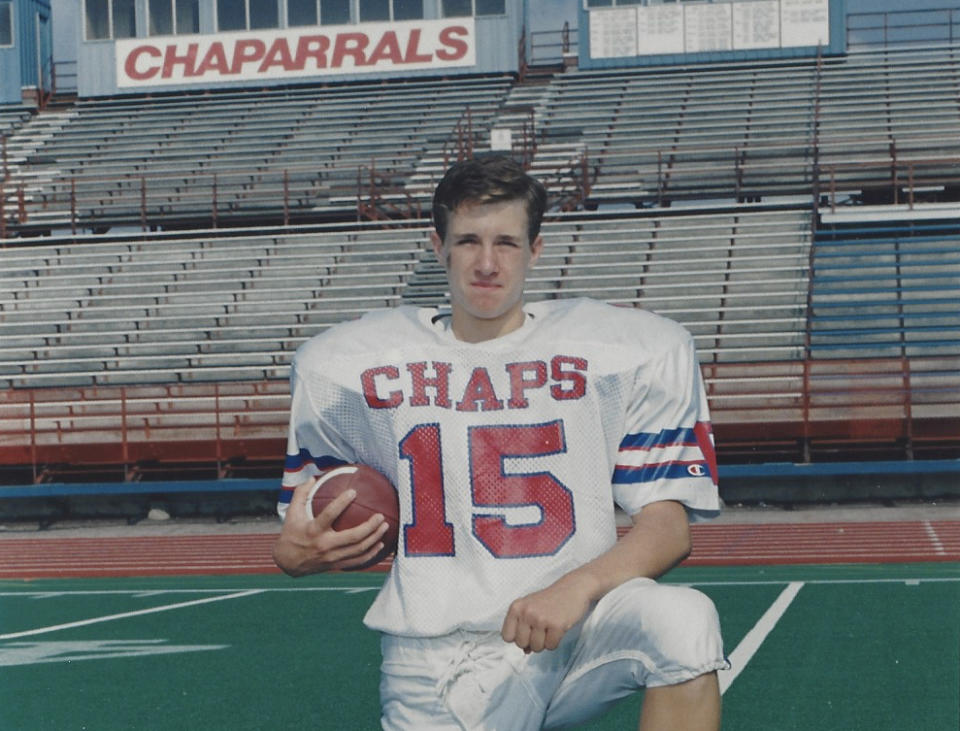

A quarter century ago, Drew Brees wasn’t even the top quarterback in his high school class.

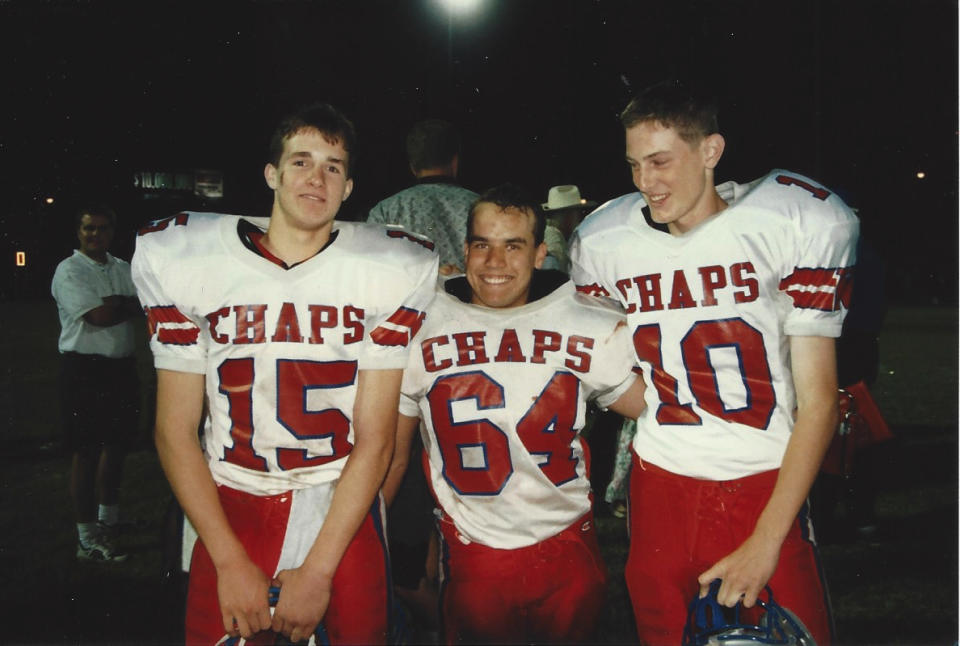

Coaches at Texas football powerhouse Westlake High School anointed Jonny Rodgers as quarterback of their freshman A team in 1993 and began grooming him to take over as the varsity starter two years later. Relegated to quarterbacking the B team was Brees, then a scrawny private school transfer who had never played tackle football before.

While Brees already had a slightly more powerful, accurate arm than Rodgers by that point, he was not as good a fit for the option-style attack Westlake favored at that time. Not only was he wholly unfamiliar with the system, he also lacked the elusiveness to evade defenders in the open field or the muscle to withstand big hits.

The son of a University of Texas assistant coach and younger brother of Westlake’s varsity starting quarterback at the time, Rodgers boasted the requisite strength, speed and agility for a dual-threat quarterback. He also was already comfortable with the system, having run it while quarterbacking one of the middle schools that feeds into Westlake.

“I thought I was going to be the guy,” Rodgers said. “My brother Jay was going to be a senior when Drew and I were going to be sophomores, and it was kind of set up for me to take over the following year. There was no indication in my eyes that there was someone who was going to take my spot, especially not someone in our class.”

Rodgers was so entrenched as Westlake’s heir apparent at quarterback that Brees briefly pondered giving up football early in his sophomore year. One hot August day, a frustrated Brees came home from two-a-day practice and told his mother he wanted to concentrate solely on baseball, but she urged him to be patient and forbade him from quitting in the middle of the season.

Everything changed for Rodgers and Brees only days later during Westlake’s final preseason junior varsity scrimmage against Killeen High School. As Rodgers rolled right and planted to throw, his knee buckled and his football future flickered.

Suddenly Rodgers was facing nine months of grueling rehab and the possibility that he had squandered his chance to follow his older brother as Westlake’s next standout quarterback. Suddenly Brees was Westlake’s JV starter, the break he needed to prove himself to a coaching staff that until that point had been reluctant to give him a real chance.

“I can’t say what would have happened if Jonny hadn’t torn his ACL,” former Westlake football coach Ron Schroeder said. “If Jonny had been healthy his entire sophomore year, that would have kept Drew on the B team in all probability because Jonny was good enough not to be benched. We could very well have stuck with Jonny Rodgers at quarterback, and you probably wouldn’t know who Drew Brees is.”

It took awhile for Brees to match his genetic destiny

Schroeder might have given Brees a chance more quickly if someone had made him aware of the young quarterback’s impressive bloodlines.

Brees’ father is Eugene “Chip” Brees, who played basketball at Texas A&M. His late mother is Mina Akins, a four-sport athlete and all-state basketball player at Gregory Portland High School. His maternal grandfather is Ray Akins, one of the winningest coaches in Texas high school football history. And his uncle is Marty Akins, a wishbone-style quarterback at Texas who started for two years in the same backfield as Earl Campbell.

Blessed with enviable genes, an insatiable competitive spirit and parents who encouraged him to dabble in numerous sports, Brees excelled at nearly everything he tried as a kid.

He starred for a prestigious youth soccer club in elementary school until the schedule became too demanding for him and his parents. He hit third in the batting order for all his youth baseball teams and often dominated from the pitcher’s mound as well. He was once the state of Texas’ top-ranked youth tennis player, just ahead of future U.S. Open champ and World No. 1 Andy Roddick.

Yes @drewbrees beat me in tennis when I was 9 and he was 11. Twice…. I finally beat him and he quit tennis. You're welcome football

— andyroddick (@andyroddick) January 11, 2014

“He was always the kid growing up who could pick up a golf club, a ping pong paddle, a tennis racket, a baseball, a football, and it was like he had been doing it for years,” childhood friend Ryan Riviere said. “From the first time I met him in Little League, it was apparent he was the best player on our team, and it wasn’t even close.”

Football was the one sport Brees had yet to conquer before he got to Westlake. He had started at quarterback for his private middle school’s flag football team, but that didn’t remotely prepare him for a role on one of the top high school teams in Texas’ highest-enrollment division.

When Westlake held its first intrasquad scrimmage prior to Brees’ freshman season, he didn’t play a single snap. He had never lifted weights before. He had not yet physically matured. And while he offered occasional glimpses of uncanny accuracy as a passer, he required a long, looping wind-up to zip passes into tight windows because his arm strength was not yet up to par.

“At that time, he didn’t really stand out,” Schroeder said. “He was just a young kid who was still growing. He wasn’t very strong. He wasn’t very fast. But he was working hard.”

By the time Rodgers’ knee injury forced the Westlake coaches to find someone else to serve as JV starting quarterback, Brees had begun to close the gap between himself and his classmate. He still wasn’t physically imposing, but he now displayed newfound familiarity with Westlake’s system and a knack beyond his years for recognizing blitzes, reading coverage schemes and finding open receivers.

Brees threw for 300 yards and four touchdowns in his first start and quarterbacked Westlake’s JV team to a perfect 10-0 record during the 1994 season. Schroeder didn’t formally name Brees the 1995 varsity starter until the following spring, but Rodgers was shrewd enough to recognize long before then that he’d lost his grip on the job.

“Drew came in and just ignited our offense,” Rodgers said. “As soon as I saw how well he was playing, I knew pretty quickly the only way I’d ever see the field was to learn the defensive side of the ball.”

How Drew Brees seized control of a team

As Rodgers transitioned to free safety and became a leader on the Westlake defense, Brees quickly demonstrated he’d have no problem making the leap from JV to varsity quarterback. He amassed a 28-0-1 record in two seasons as the varsity starter and threw for more than 5,000 yards and 50 touchdowns, displaying improved throwing mechanics on the practice field, command of the offense in the pocket and leadership beyond his years in the huddle.

A Westlake team loaded with senior starters ripped through its regular-season schedule without a loss during Brees’ junior year before disaster struck in the third round of the state playoffs. This time it was Brees who tore an ACL when he planted wrong trying to steady himself after a blitzer blindsided him on a naked bootleg.

Expectations were more modest for Westlake the following season with Brees only nine months removed from knee surgery and most of the previous year’s starters lost to graduation. All Brees did was come back with newfound resolve, win the Texas 5A offensive player of the year award and lead Westlake to its lone state championship in program history.

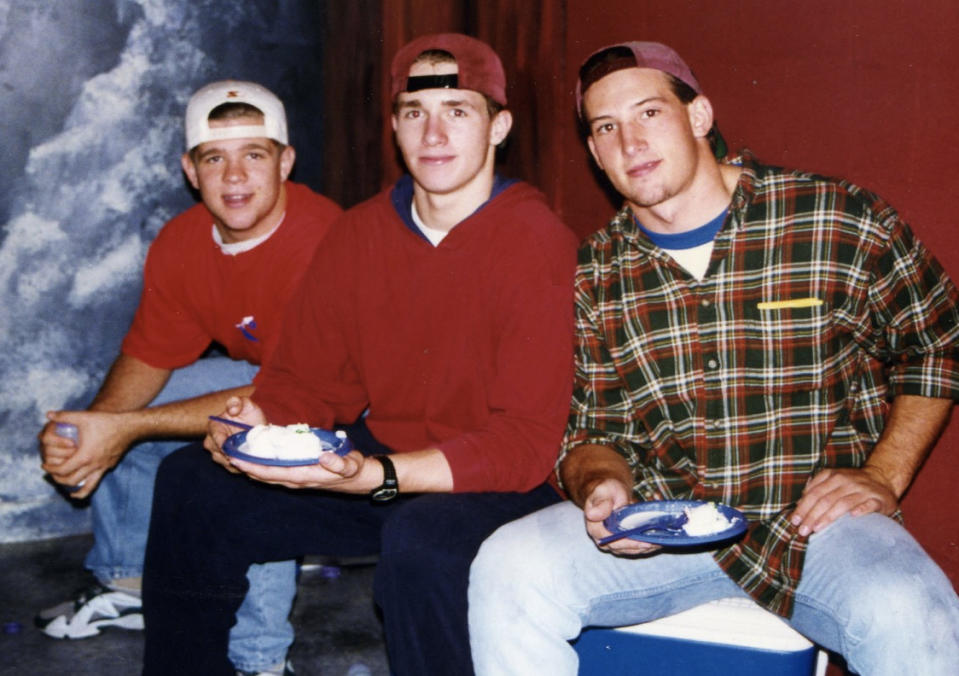

No one was a bigger supporter of Brees during that time period than Rodgers, a testament to the character they both possess. The former competitors grew to be such close friends that Rodgers actually led a “Drew Brees” chant in the huddle after one particularly memorable playoff win at the Alamodome.

“Brees was so good, so humble and so likable that Jonny couldn’t help but to become a fan,” Schroeder said. “There wasn’t any doubt in anyone’s mind during their senior year that Drew was the quarterback. I think Jonny saw that and I also think Jonny enjoyed playing free safety and becoming a leader on defense too.”

The offensive player of the year in Texas’ highest-enrollment division typically has his pick of colleges, but that was not the case for Brees. Remarkably, not a single Division I college had offered Brees a scholarship by the end of his sterling senior season.

Since Brees’ ill-timed knee injury prevented him from participating in any camps and recruiting combines the summer before his senior year, many college coaches either missed the chance to get to know him on a personal level or were unfamiliar with him altogether. Those that were aware of Brees were hesitant to commit to a quarterback who stood barely 6 feet tall in cleats and possessed only average speed.

“We were hopeful there would be some interest in Drew in the offseason after his junior year and then the knee injury occurred,” said Chip Brees, Drew’s father. “We didn’t get scholarship offers, phone calls, letters, nothing. Whatever interest there had been in Drew before that point was derailed.”

Especially harmful to Brees was disinterest from the University of Texas, a program whose campus was a 15-minute drive from Westlake’s and whose recruiting coordinator was Rodgers’ father. The Longhorns pursued quarterback prospects Major Applewhite and Marty Cherry instead of Brees, a snub that no doubt fueled the doubts of other top programs in Texas and beyond.

Texas A&M was Brees’ childhood favorite school and the alma mater of his mother and father, yet the Aggies chased other quarterbacks. Baylor, SMU and Texas Tech each received calls on Brees’ behalf from his coaches or family members, but they too declined to pursue him. Chip even paid for he and his son to visit North Carolina, Duke and Virginia out of his own pocket while Brees was still rehabbing his knee injury, but coaches from those schools had no interest in meeting with the future NFL quarterback while he was on their campuses.

“We heard back from someone on Mack Brown’s staff [at North Carolina] saying basically thanks but no thanks,” Chip Brees recalled. “‘You’re welcome to come visit the university, but we don’t have time to visit with you.’

“It just seems logical to me that if the college program in your backyard is not recruiting you, other programs are going to think, ‘What do they know that we don’t? They see the kid every week. They must know more than everybody else. Maybe there’s a reason they’re not recruiting him.’”

Enduring friendship for Rodgers, Brees

Brees might have quarterbacked an Ivy League school or pursued a baseball scholarship had a pair of pass-happy football coaches not become enamored with him in the nick of time. Purdue’s Joe Tiller and Kentucky’s Hal Mumme both had scholarships available late and came to view Brees as their quarterback of the future after watching him spearhead Westlake’s spectacular run through the Texas state playoffs.

Purdue won a brief battle to land Brees because of the strength of its academics, the prestige of the Big Ten and the possibility of early playing time. Kentucky’s pitch to Brees was to redshirt and sit behind Tim Couch for another year before potentially winning the starting job in Year 3.

In many ways, landing at Purdue instead of Texas or Texas A&M may have been a blessing in disguise for Brees. It gave Brees the chance to earn playing time quickly and showcase himself to NFL scouts in a pass-oriented offense tailored to his strengths.

As Brees prepared to begin his college football career at Purdue, Rodgers was coming to grips with hanging up his cleats for the final time. He had suffered a second torn ACL in the waning minutes of the state championship game, shuttling his plans to play quarterback at TCU as a preferred walk-on.

“I thank God everyday that I blew my knee out a second time because it forced me to realize it was time to do something else,” Rodgers said. “I went to TCU, had a great time, came back to Austin, got into real estate and I’m enjoying life here.”

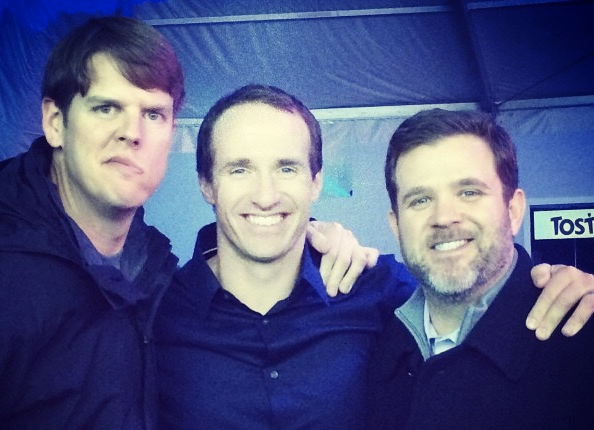

Twenty-one years after they graduated high school, Brees and Rodgers remain close friends. They contribute to one-another’s charitable causes and talk or text regularly, the subject usually former classmates and funny memories rather than anything to do with pro football.

Because it was Rodgers’ fateful knee injury that opened the door for Brees to launch his football career, the two men will be forever tied.

Were it not for Rodgers’ misfortune, who knows if Brees would be entering Monday night’s game 201 yards away from breaking Peyton Manning’s all-time NFL passing yardage record? Maybe Brees wouldn’t have played football beyond high school at all.

The link with Brees is something Rodgers’ friends tease him about all the time. Instead of introducing him to strangers as a successful real-estate agent, a generous philanthropist or the city of Austin’s 2015 man of the year, Rodgers’ oldest friends often prefer to highlight that he once started ahead of one of the NFL’s premier quarterbacks.

“Looking back, it is a lot easier to say that I got beat out by Drew Brees rather than some random guy,” Rodgers said. “I like to think it was God’s plan. We’re going to move you aside. We’ve got some other cool things for you in the future outside of football, but right now we need to put everything on this Drew Brees kid because he is special.”

– – – – – – –

Jeff Eisenberg is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at jeisenb@oath.com or follow him on Twitter!