Then and Now: Looking back at 150 years of Churchill Downs and the Kentucky Derby

If the first Kentucky Derby spectators suddenly found themselves at the front gates of Churchill Downs today, they wouldn't recognize anything. So much has changed in 149 years.

The first “Derby Day” on May 17, 1875, looked nothing like the international spectacle that draws hundreds of thousands of people to a storied racetrack rigged out with bars, clubs and ballrooms in what has become known as the "Derby City." In nearly 150 years, the event has garnered a legacy as a time-honored tradition, robust with pageantry and celebrated as one of the premier horseracing events in the world.

But imagine a Kentucky Derby flanked in 19th-century farmland, freckled with lawlessness and operated by the primitive technology of the day. So many of the practices, amenities and traditions modern Derbygoers relish in weren’t part of the original experience.

Jessica Whitehead, curator of collections for the Kentucky Derby Museum, said the only part of the storied racetrack that hasn’t shifted since the first Kentucky Derby Day in 1875 is the footprint of the track. In 149 years the race has grown into an undeniable success, so much so that beyond the horses, the jockeys and the dirt its humble and ambitious beginnings are nearly invisible in the modern event.

10% of Louisville's population attended the first Kentucky Derby

Today racegoers at Churchill Downs are shuttled to the track on a meticulously choreographed system of air-conditioned buses through a cluster of automobile traffic. Derby regulars befriend the track’s residential neighbors, so year after year they can park in a jigsaw-like puzzle of cars arranged on these homeowners’ lawns.

Each year more than 150,000 people finagle their way into the bottleneck of the track for the "Most Exciting Two Minutes in Sports." While the Kentucky Derby certainly predates cars, automobile traffic, and even the neighborhood that surrounds it, one thing remains abundantly clear: Getting the crowd to the track poses a challenge.

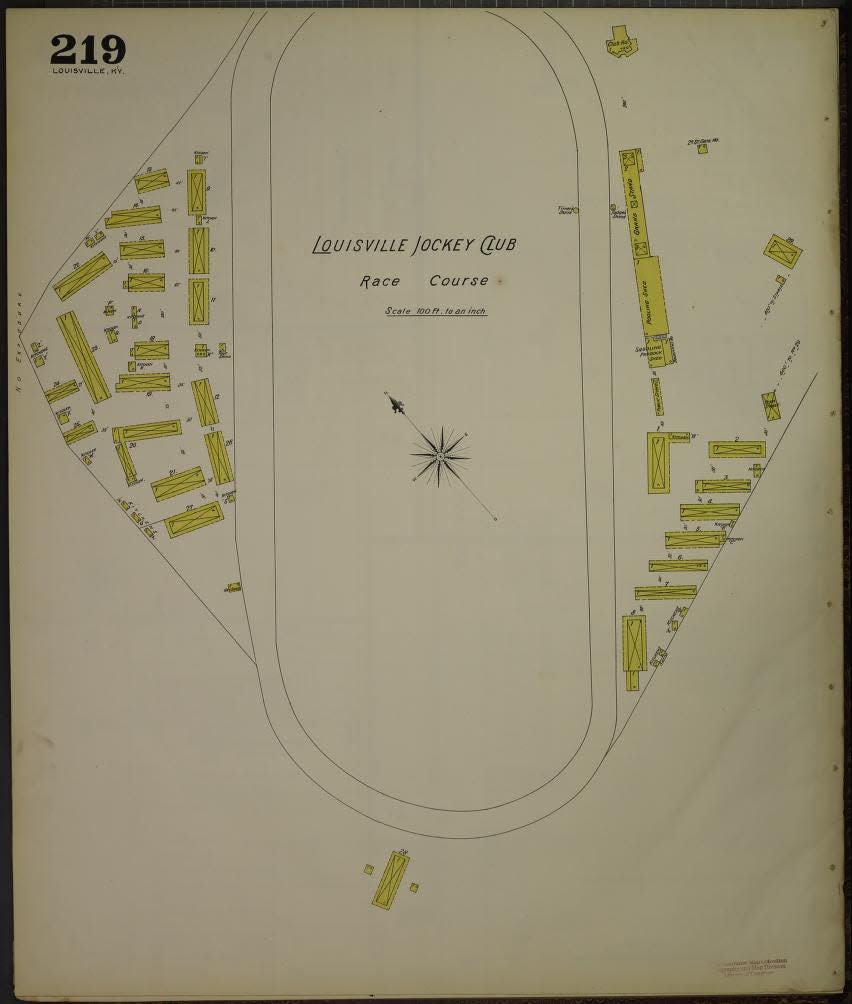

Louisville had been on the map for nearly a century when Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. set out to build an epicenter for horseracing. But where that city map and its limits stretched to didn’t include the land where Churchill Downs sits.

Steve Wiser, a historian with Louisville Historical League, compares it to driving about 30 miles north on Interstate 71 to rural Oldham County. It’s a mental leap for someone more in tune with the urban core, and that's what the track site felt like in the 1870s when Clark began making plans. At the time, the waterlines and streets didn’t reach where he wanted to build, so Clark pled with the city to extend them.

In addition, the horse-drawn streetcar line in that era stopped near Central Park. Clark dreamed of building out Third Street into a picturesque promenade, similar to Union Avenue near Saratoga Race Course, that would make the four-mile carriage ride from the city center seem like a pleasant afternoon, rather than an inconvenience.

Eventually, Clark got his wish.

Over the next several years, elegant architecture flourished into what’s now one of the largest collections of Victorian homes in the country. Today it’s called “Old Louisville,” but back then it was merely an idea.

Without that infrastructure, the easiest way to transport the 10,000 or so people south for the race was using rail lines that ran near the track.

Clark was preparing to welcome a crowd equivalent to 10% of the city’s population, Wiser explained, and that wasn’t an easy task. In the days leading up to the race, The Courier Journal published schedules geared at getting as many people to the inaugural Kentucky Derby as possible. The fare was as little as 25 cents to the old L&N depot or 55 cents to New Albany, and the jockey club’s leadership worked with the railroad company so that two locomotives would be waiting outside once the races ended.

Whitehead suspects the crowd was overwhelmingly Kentuckians. Some people in the horse racing circuit may have traveled in from neighboring states such as Tennessee, but the race wouldn’t evolve into a destination for decades.

That’s partially because the Civil War had devastated racing in the South, Whitehead explained, but it also had to do with logistics and the region’s reputation.

“It really would have been Kentucky's Derby at that point, it was not America's Derby,” Whitehead said. “We were considered the Wild West for a lot of people on the East Coast.”

What was downtown Louisville like in 1875?

Even so, in the weeks leading up to the first Kentucky Derby, Louisville was hoping to draw in the masses.

Kentucky’s largest city had “a direct railroad connection within every quarter of the whole country and ample accommodations for thousands of visitors,” The Courier Journal reported at the time.

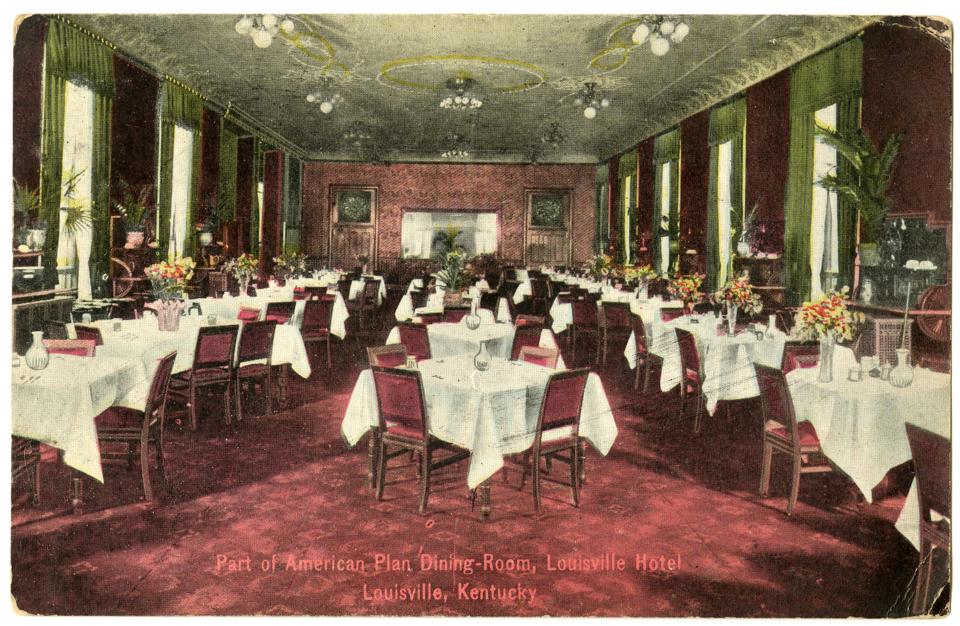

But those “ample accommodations” look nothing like today.

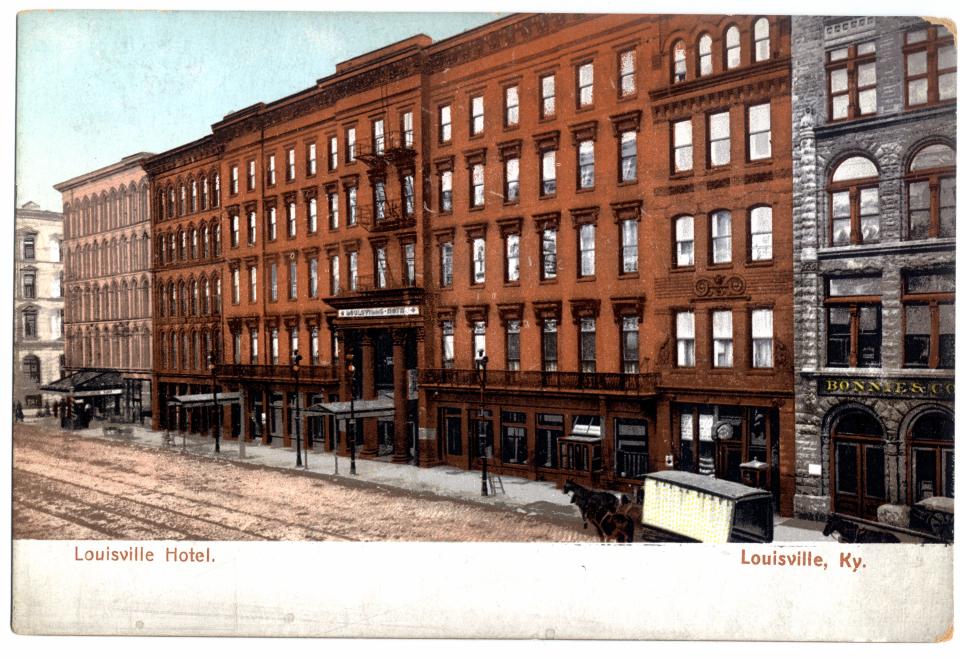

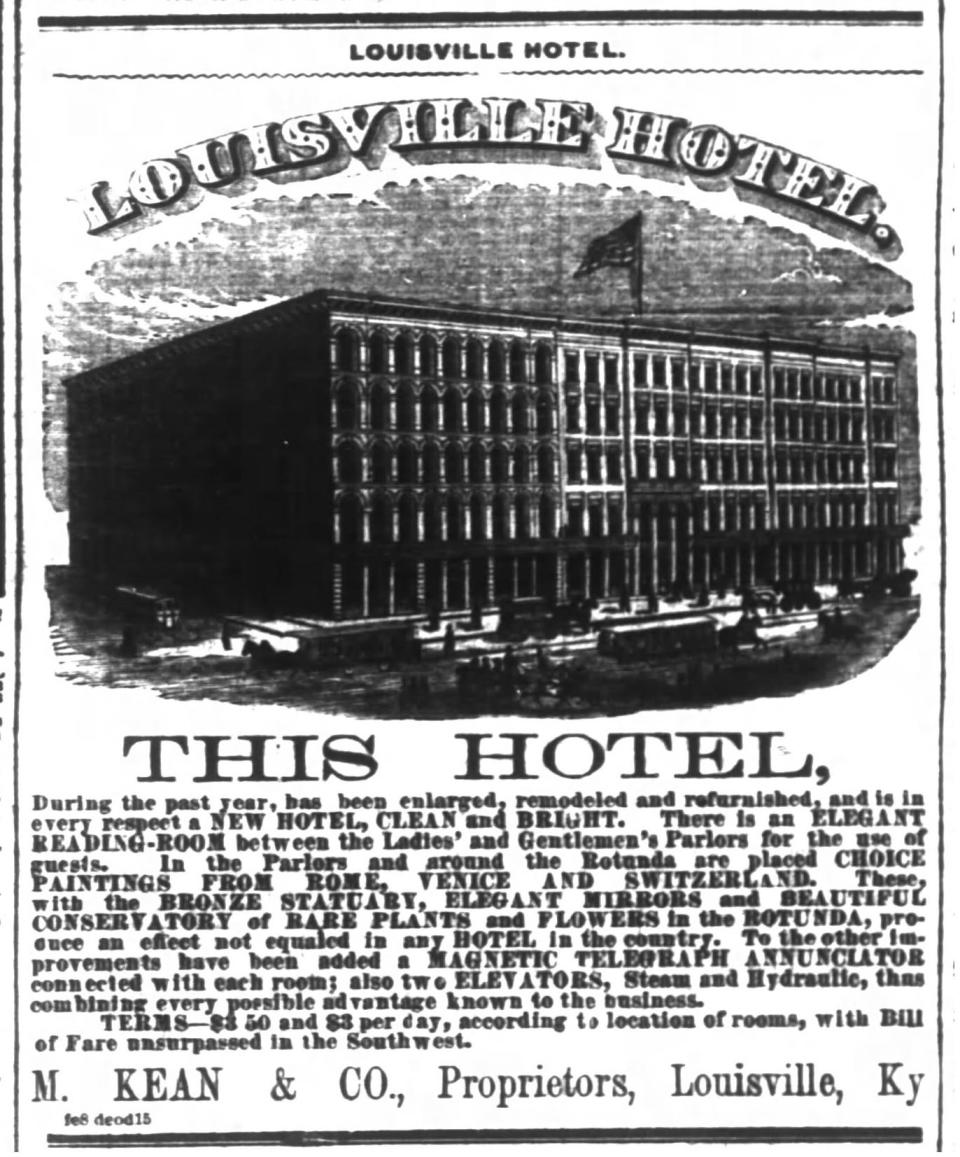

The iconic Brown Hotel on West Broadway is nearly synonymous with the Kentucky Derby, but it couldn’t host guests that first year, or for decades to come. The Brown opened almost 50 years after the inaugural Kentucky Derby.

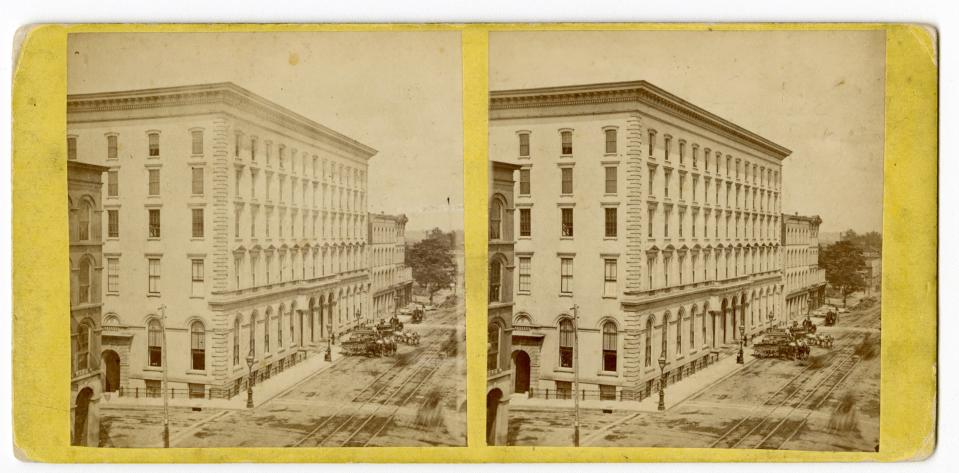

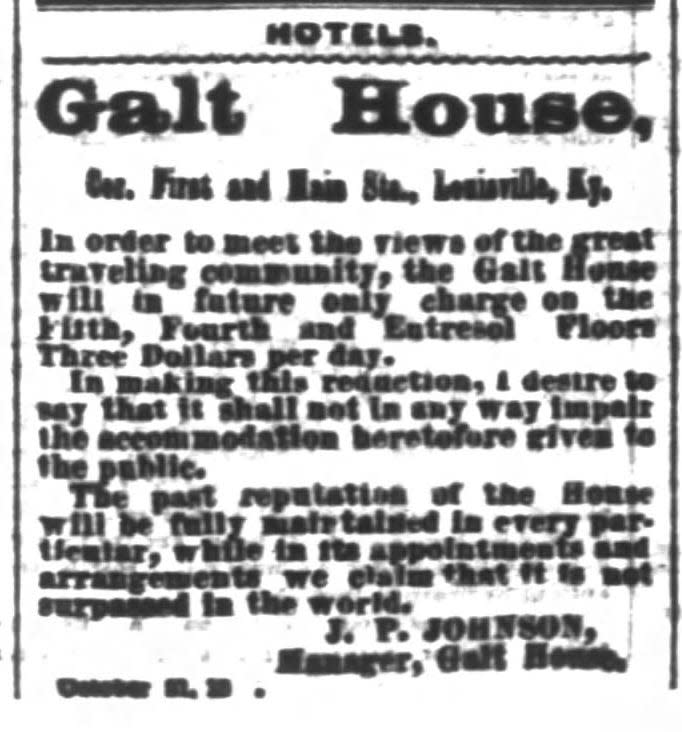

Instead, The Galt House and the Louisville Hotel were the best known among the 35 or so lodging spots scattered among downtown, Wiser said. Most of those would have been mansions converted into boarding spaces, rather than the towers that reach into the sky today.

Courier Journal advertisements from that period boast the Louisville Hotel had the luxury of two elevators onsite so guests could reach all five stories without taking the stairs. The listing also touts that each room is connected to a magnetic telegraph annunciator, a system of bells guests could use to summon the hotel staff.

Even with those standout amenities to welcome visitors, Clark was adamant the Kentucky Derby was for everyone.

Admission to the track for that first Derby was as little as a dollar, about $28.21 in current currency. The tickets could be picked up at the Galt House.

In 1975, $10 could get you into the festivities at the track for the whole week. Today, most tickets to the grandstand on Kentucky Derby Day cost upward of $500.

The original grandstand at Churchill Downs

Historic weather reports show the first Kentucky Derby ran under a clear sky with a high of 68. That's a dream for 21st century ticket holders as they plan their outfits each year for the first Saturday in May.

In 1875, however, that picture-perfect day may have complicated matters at Churchill Downs.

Fabrics for elegant clothing were heavier back then, and air conditioning was a far-off dream. The trouble was less about the spring air, though, and more about architecture.

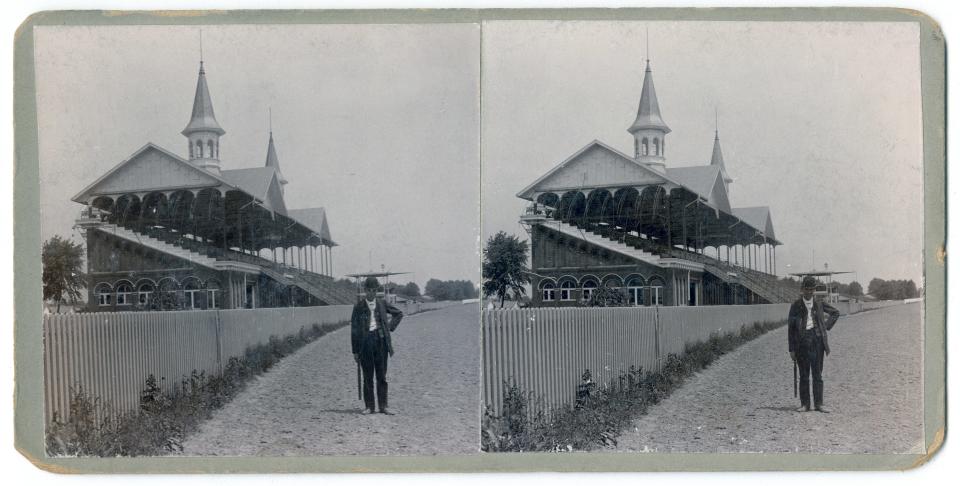

The track’s original grandstand stood opposite where it is today ― facing the afternoon sun. The race predated the mass production of sunglasses by decades, meaning many would have squinted their way through the two minutes and 37 seconds it took the first Kentucky Derby winner, Aristides, to cross the finish line.

You may like: Courier Journal publishing '150 Years of the Kentucky Derby' coffee table book. How to pre-order

“They're all drinking liquor and having a good time, and that western sun beating down on them,” Wiser said. “A lot of them are probably pretty well under the weather by the close.”

With that in mind, it’s no surprise Churchill Downs moved the grandstand a few years later.

The first Kentucky Derby was the second of just three races on May 17, 1875, and to the modern 14-race spectator, that may seem like a short day, especially when you consider that four-mile journey to the track.

But races didn’t run quite as smoothly back then.

Auction-like gambling at the Kentucky Derby

For one thing, gambling was more complicated. The Louisville Jockey Club printed programs for that first day of racing, but they were more of a guide than a resource filled with handicapping charts. Those charts would come much later. (Oliver Lewis, the Black jockey who won the first Kentucky Derby, went on to develop those after he retired from riding.)

Even so, the words, horses and information listed among those 1875 pamphlets could have seemed just as complex as the numbers and stats circulated today.

One in four Kentuckians was illiterate in the 1870s.

To wager, men gathered in the “pool house” for an auction-like environment, Whitehead explained. The idea was to divide the wagered total between the winners in a manner loosely comparable to the modern lottery system. Imagine a packed room with men shouting over one another to put their money on their favorite horse.

“So this is very, very unfamiliar to the kind of betting that we do (today) and not necessarily terribly democratic and or accessible,” Whitehead said.

As genteel and upscale as Clark might have envisioned his track, this was still 19th-century Kentucky. Think fist fights and even gun-toting without the protections of today’s security. Alexander Graham Bell wouldn’t invent the first metal detector for another six years, and it would be decades before that technology evolved into the meticulous security screening of 21st-century events.

“Kentucky would have still been pretty lawless at that point,” Whitehead said. “The Louisville Jockey Club might have been a little lawless in terms of the atmosphere, too.”

Life in the 'ladies pavilion' and 'Clubhouse' at Churchill Downs

The first Kentucky Derby could be called a boys' club, and while women did attend, they needed a male escort.

“They would have restricted areas where they were permitted to go,” Whitehead said. “And the betting shed was out because there was gambling or swearing or smoking — all the things women in the 1870s had to conveniently forget existed.”

They could only watch the race from the ladies’ pavilion in the grandstand or a select few could enjoy the “The Clubhouse,” where high society gathered.

Think of this as the 19th-century equivalent of the famed “The Mansion,” where only the most elite VIPs watch the race and enjoy the finest luxuries of the day. But not the luxury Chanel make-up artists in the powder room or Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto carving tuna for sashimi might expect today.

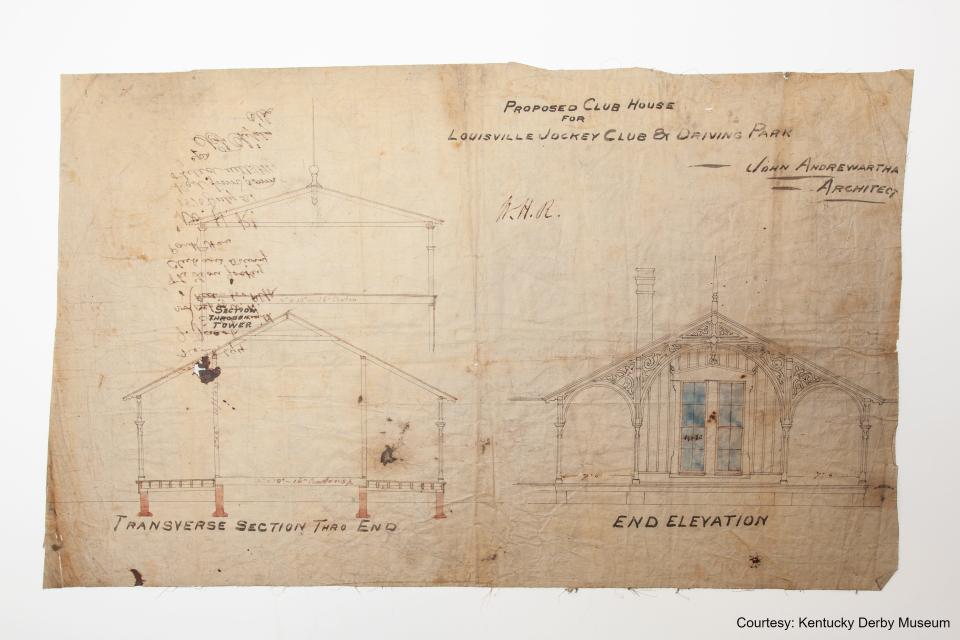

Instead, the original renderings from The Clubhouse indicate it was the only place on Churchill Downs property with “water closets,” which was 1875’s version of indoor restrooms. It had a kitchen onsite for food service, which would have been groundbreaking.

Spectators on the track and a race without a starting gate

One thing that hasn’t changed at Churchill Downs over a century and a half is offering guests a variety of experiences at different price points.

The bottom-shelf experience — the famed party zone in the center of the track known as the infield — has welcomed guests since the first Kentucky Derby. For decades people flocked to the infield for a good time, but until a $12 million, 4K ultra-high-definition video board was added in 2014, many never saw a horse the entire day.

That wasn’t necessarily the case in 1875.

At the time, Churchill Downs didn’t have a tunnel that ferried people from the infield to the grandstand. So, to reach the grassy infield, the crowd would have to walk across the track to get to the space in the center.

Photographs from the 1920s show spectators standing on the track while races run. Reasonably, Whitehead said, crowd members could have lingered on the track during the first Kentucky Derby, too.

Even more unbelievable than that is how the Louisville Jockey Club began races before the starting gate was introduced in the 1930s.

Instead, workers would line up the horses and hold them by the rump in position, Whitehead explained.

In those days, a drummer cued the release of the horses and the beginning of the race.

As Aristides charged the finish line, he would have run beneath a wire that racing stewards used to eyeball the winner. The phrase “down to the wire” dates back to this common method of 19th-century horse racing. "Photo finish" technology wouldn’t come on the scene until 1890.

150 years of changes

On May 17, 1875, there was no way to know that 149 years later, Clark’s vision would grow into the longest, continuously held sporting event in the country.

Throughout its history, Churchill Downs has existed as an ever-changing microcosm for the advancements of society. The track and the Kentucky Derby have sustained themselves by evolving to stay relevant.

Small changes, like adding that starting gate and allowing women to roam the stands and place bets, have turned the Kentucky Derby into a phenomenon.

No one who attended the first Kentucky Derby would recognize the track today, but Whitehead said you can make that argument for every race in the early 20th century.

The first grandstand had already come down and the twin spires had gone up. The tunnel to the infield reshaped the whole experience when it was built in 1937. The next year, collectible mint julep glasses that fill the homes of Derby enthusiasts made their first appearance. The star-studded red carpet didn’t exist for the first half of Derby history as Hollywood was in its infancy.

Though nothing may look the same, the thrill when the horses thunder around the track remains.

That emotion hasn’t waned in a century and a half and likely won't for generations to come.

Reach features columnist Maggie Menderski mmenderski@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Look back at 150 years of Churchill Downs and the Kentucky Derby