The greatest call ever: The story of Vin Scully's ninth inning of Sandy Koufax's perfect game

It was 9:46 p.m. on September the 9th, 1965, and all anyone heard on the AM radio signal beaming from KFI to the world was noise. At first it was 29,139 people sounding like a million and then a woman’s wail overpowering the masses and then a whistle reverberating and another whistle and another. And only then, as the voices yielded to the limits of their larynx and the euphoria at Dodger Stadium started to evaporate, did the man on the radio deign to speak again. For 38 seconds, he had let cacophony finish the story he’d told with such melody. Now he needed a bookend.

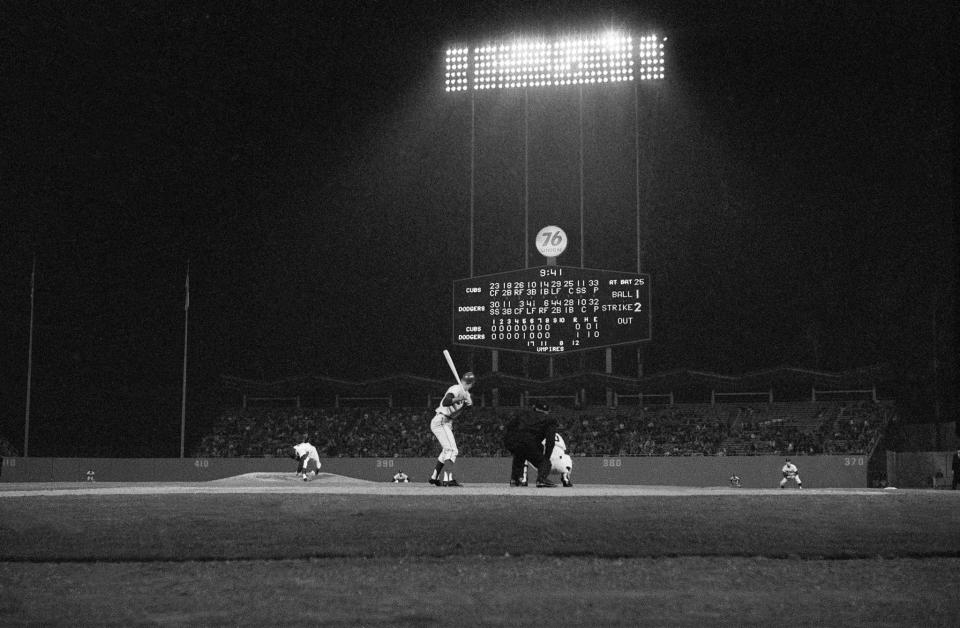

“On the scoreboard in right field,” Vin Scully said, “it is 9:46 p.m. in the City of the Angels, Los Angeles, California. And a crowd of 29,139 just sitting in to see the only pitcher in baseball history to hurl four no-hit, no-run games. He has done it four straight years, and now he capped it: On his fourth no-hitter he made it a perfect game. And Sandy Koufax, whose name will always remind you of strikeouts, did it with a flourish. He struck out the last six consecutive batters. So when he wrote his name in capital letters in the record books, that ‘K’ stands out even more than the O-U-F-A-X.”

It was to that point, and maybe still, the greatest game ever thrown: 113 pitches, 79 strikes, 14 strikeouts, all with an arm that between starts found itself jabbed with thick-gauged needles to remove excess fluid and rubbed with chili pepper extract to numb the pain. Koufax warranted every bit of adulation, though it would be wrong in hindsight not to acknowledge another truth every bit as evident today as it was exactly 51 years ago.

That night, at Dodger Stadium, in the City of Angels, Los Angeles, California, there were actually two perfect games.

Perfection is 27 outs and 1,028 words. It is 1 hour, 43 minutes of baseball and 8 minutes, 45 seconds of a radio broadcast. It is a fastball and a quick wit, a curveball and a willingness to bend convention. It is Sandy Koufax and it is Vin Scully, one artist playing muse to another.

“Three times in his sensational career has Sandy Koufax walked out to the mound to pitch a fateful ninth where he turned in a no-hitter,” Scully said to start the ninth inning of a game that personified mid-1960s baseball. Hits were hard to come by – 1965 was the leanest year for them in nearly half a century – and the Dodgers had managed one all night, a seventh-inning bloop double by Lou Johnson, who two innings earlier had scored the game’s only run on a walk, sacrifice, stolen base and overthrow.

Twenty-four times a Chicago Cubs player had stepped in against Koufax, and 24 times had he retreated to the bench defeated. First up in the ninth was Chris Krug, the Cubs’ catcher whose error gifted the Dodgers their run, and Koufax started him off with a curveball for a strike. Krug swung through a fastball for strike two, and Scully delivered the first of an inconceivable number of memorable lines for an off-the-cuff broadcast: “You can almost taste the pressure now.”

By then, Dodgers fans understood what all these years later we now know: Scully endeavors to turn baseball into a multisensory experience in which he acts as our eyes and nose and hand and even our tongue and amalgamates them into something we consume with our ears. He limned the world before him and allowed us to dream it: “Koufax lifted his cap, ran his fingers through his black hair, then pulled the cap back down, fussing at the bill. Krug must feel it too as he backs out, heaves a sigh, took off his helmet, put it back on and steps back up to the plate.”

As Krug took a ball and fouled off the next pitch, Scully stopped to name all nine Dodgers on the field. He called the infielders “the boys who will try to stop anything hit their way,” and, after scrolling through the outfielders, said: “And there’s 29,000 people in the ballpark and a million butterflies.”

At 37 years old then, and today just the same, Scully made even the rote sound exquisite, his choice of words and mellifluous voice imbuing gravitas. The tension of Krug’s at-bat resonated because Scully felt it, too. Another foul ball. Another ball, outside, which caused boos toward the umpire that Scully knew unfair. “A lot of people in the ballpark now are starting to see the pitches with their hearts,” he said.

Never did Scully fall into that trap. For 16 years he had called Dodgers games with dutiful equilibrium. To lapse into homerism would be disingenuous. Scully knew the best play-by-play men trafficked in facts, not emotions. Much as he admired and rooted for Sandy Koufax, Scully recognized play-by-play is meant to exist in a church-and-state world, where the story of the game supersedes all.

That didn’t stifle his enthusiasm. On the contrary, Scully called Krug’s strikeout on a fastball with the proper fervor before segueing back to the facts: “Sandy Koufax has struck out 12. He is two outs away from a perfect game.” Scully was, and five decades later remains, the master at never allowing the situation to overwhelm him so much he forgets to pair his aural candy with the necessary meat and potatoes.

After pinch hitter Joe Amalfitano fell behind 0-2 and left the batter’s box, Koufax stepped off the rubber and paced behind it. “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world,” Scully said, and counterintuitive though it sounded – a man with tens of thousands of people urging him toward something achieved only seven times, lonely – Scully echoed the reality of every pitcher. The mound is isolated, secluded, desolate, the domain of one and only one, the vise of the moment ever squeezing.

Amalfitano waved at a fastball for the third strike, bringing up pinch hitter Harvey Kuenn. “The time on the scoreboard is 9:44,” Scully said. “The date, September the 9th, 1965.” It was his second mention of the time and third of the date. This was intentional. Whenever a no-hitter went into the ninth inning, Scully asked his sound engineer to start recording a tape so he could deliver a copy of the live broadcast to the pitcher. Scully always included the date so the pitcher could play the tape for his grandchildren and give them a sense of how long ago it took place. The addition of time was almost ornamental, a special souvenir for Koufax that Scully never intended to become one of the defining moments of the call.

Koufax started Kuenn with a fastball for a strike, then missed high on a pair, including one pitch after which his hat flew off his head. “You can’t blame a man for pushing just a little bit now,” Scully said. “Sandy backs off, mops his forehead, runs his left index finger along his forehead, dries it off on his left pants leg.” This was classic Scully: universal observation followed by vivid scene description. The king of muscular verbs – mop and taste and fuss and heave – Scully always respected his audience enough not to pander to the lowest common denominator.

On Koufax’s 14th pitch of the inning, Scully didn’t call the pitch type for the first time. It was a strike, which meant Koufax was one away, which prompted another time check: “It is 9:46 p.m.” Ten seconds later, Scully uttered the words for which he’d waited all night: “Swung on and missed! A perfect game!” He was speaking for Sandy Koufax. He just as well could’ve been for himself.

In old, dusty vinyl collections across Los Angeles, a gem of a record lurks, unspun in decades. At the top of the label, it reads: Danny Goodman. He was the Los Angeles Dodgers’ marketing guru who, among other things, introduced the United States to bobbleheads. Goodman would sell anything, including the record that on the bottom of the label said:

Last Inning Sandy Koufax

Perfect Game

Actual Reproduction as

Narrated by Vince Scully

Every so often, a copy of Goodman’s version or another record company’s will crop up on eBay. It’s the nostalgic way to re-live the ninth inning, just as Jane Leavy’s peerless biography, “Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy,” weaves his life story through the prism of the entire perfect game, from his childhood to the Yom Kippur game in 1965 to his retirement a year later. The book also fills in the first eight innings, with Scully’s call never again heard publicly.

At least one copy exists – and Sandy Koufax owns it. A fan approached him with a scratchy recording off a transistor radio. It’s missing the first inning, but the rest is there, all for Koufax to listen to, to enjoy, the baseball version of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin.

Scully has been the world’s long enough that there’s something romantic about leaving this slice of history to the person who inspired it. The ninth inning is enough, really, a delightful encapsulation of Scully’s 67-year career calling Dodgers games, which ends when their season does. Losing Scully – his voice, his knowledge, his tangential stories, his measured, old-timey delivery – will hurt the game, a premise Scully himself would find laughable. He’s just a play-by-play man, after all. A voice.

And yet those 1,028 words in those 8 minutes, 45 seconds in which the breadth of his repertoire ingrained itself into baseball lore make a compelling point otherwise. Vin Scully isn’t just anything. He’s everything.