We Still Don't Understand the Yips

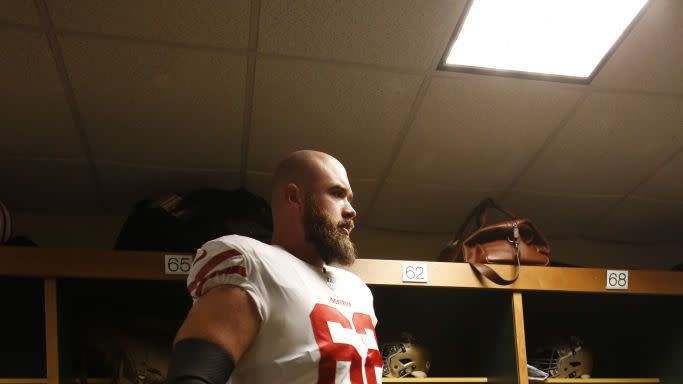

Erik Magnuson was barely clinging to his roster spot on the San Francisco 49ers. Since signing with the team as an undrafted free agent in 2017, the offensive lineman had been nursing a never-ending cycle of soft-tissue injuries, beginning with a torn Lisfranc as a rookie. Within 20 months, the then-23-year-old suffered several calf strains, torn hamstrings, as well as back and neck injuries. When the 2018 NFL season began, Magnuson was desperate to get on the field for the first time, but he was nursing another torn hamstring.

October 28, 2018 was not supposed to be his Sunday. Until it was.

The 49ers were visiting the Arizona Cardinals. When Weston Richburg, San Francisco’s starting center, suffered a knee injury, Magnuson was called on to start—despite his hamstring. Such is life in the NFL. “I had a lot of anxiety going into the game, trying to figure out how I could compensate for my lack of mobility,” Magnuson tells me over the phone during the second of our three conversations this summer, remembering the day that would change the course of his life. “I was trying to stay on the team. I felt like I was under a lot of pressure to be on the field.”

In the final minutes of the game, Cardinals quarterback Josh Rosen orchestrated a touchdown drive—giving Arizona an 18-15 lead, leaving San Francisco just 34 seconds to answer. After a few successful plays, the 49ers only needed a completion to get into field-goal range and force overtime. “We had to change the protection, so I had to push off of my right leg—which was the leg with injuries,” Magnuson says. “It happened in a split-second. I wasn't able to simultaneously snap the ball and push off of that leg. I knew the snap was bad. But I didn't know how bad.”

Magnuson soared the ball over his quarterback's head. 49ers lose. While speaking with reporters after the game, he held back tears. A fear swelled inside of Magnuson: I just played my final NFL snap. Understandably, he was fixated on what the hell happened, not what could have caused it.

Looking back now, Magnuson recognizes he wasn’t yet educated enough about his mental health to consider two of the most daunting words in sports:

The yips.

To fans on the couch, the yips jump off the television screen as a dramatic, confounding, often prolonged glitch in an athlete’s greatness. Internet trolls and sports pundits quickly pounce, throwing around the yips like harmless slang—pushing any and all opportunity for sympathy further into the shadows. There are famous examples of the yips—such as "Steve Blass Disease," where a baseball player loses their ability to throw a ball in the correct direction—and less obvious blips, like Magnuson’s. But every instance, no matter the magnitude or duration of the episode, has painful consequences.

“It was a kiss of death,” he says. "I never got the opportunity to play center again, or play in a game because I kept on dealing with injuries. I was released, rehabbing, and on practice squads. I was fighting to get on the field. As much as I could make sure that could never happen again, I never had the opportunity to show that."

In 2021, he retired from the NFL. It took Magnuson the better part of four years to start uncovering the mysteries buried within him.

Despite all the chatter about mental health in sports lately, most athletes (and fans) still struggle to understand the difference between failure and performance anxiety. The yips are a whole other beast.

The phrase is believed to have been coined by golfer Tommy Armour in the 1920s. In 2014, The New Yorker cited Armour as once describing the yips as “a brain spasm.” The condition is mostly attributed to baseball players and golfers when they lose the ability to perform fundamental functions of their craft, like pitching or putting. The yips, however, have always permeated the psyche of athletes in various sports—as well as people in various walks of life, such as surgeons and public speakers. In recent years, the term has fully worked its way into the casual sports lexicon.

In January, when Brett Maher missed four extra points during the Dallas Cowboys’ playoff win over Tampa Bay, fans reflexively called for the Cowboys to cut him before the next game. They blamed the yips, as he’d committed a crime. At the Tokyo Olympics, fans accused Simone Biles of suffering from “the twisties”—gymnastics’ form of the yips—and her commitment to her country and teammates came under fire. (Due to Biles's training demands, her representatives declined an Esquire interview, but appreciated the opportunity to advance the conversation.) As a rookie, current Orlando Magic guard Markelle Fultz dealt with a brutal shoulder injury, which led to erratic shooting. His trainer later said on the Talking Schmidt Podcast that he believed Fultz developed the yips. (The Magic declined Esquire’s request for comment on Fultz’s behalf.)

So, is there anything close to a clinical definition of the yips?

“The yips can be found in anything where you are being watched, your performance is being evaluated, and the outcome means something,” says Dr. Carrie Hastings, who has been the Los Angeles Rams team psychologist since 2018. “It’s called ‘the yips’ because it is kind of mysterious.”

“It’s good that we’re talking about mental health, but we’re still hiding the symptoms and the intricacies,” she continues, noting that she knows “several coaches” who refuse to even say “the yips.”

If we can’t say it, how will we ever comprehend it? The yips isn’t some boogeyman with a strict appetite for the ballplayers, runners, and hoopers of the world—though silence allows that stigma to thrive. But if we’re willing to listen to what an athlete with the yips goes through, we may just gain a deeper understanding of ourselves.

“Simone Biles was a breakthrough. Naomi Osaka was a breakthrough. Then, [using mental health as a catch-all term] became almost fashionable,” says Dr. David Grand, a licensed therapist who specializes in trauma. He works with athletes across baseball, basketball, football, tennis, and soccer. Notably, he previously treated Mackey Sasser, a former MLB catcher who was deemed incurable after he began struggling to toss the ball back to the pitcher. “The consciousness is there, and it’s more understood, but they talk about the mental health of the athlete and separate it from neurophysiological health.”

According to Dr. Grand, any discussion about the yips must be preceded by one about developmental trauma—and how it’s stored in the nervous system. "The yips are a form of dissociative freeze," he adds. "The brain, starting early in life, knows how to put a capsule around a traumatic experience. That capsule is a barrier. When you have repeated traumatic experiences, there’s repeated dissociative capsules. The person is carrying trauma deep in their brain and nervous system, but they don’t know it."

Dr. Grand is joined in that belief by Dr. Navin Hettiarachchi, the Washington Wizards’s former athletic trainer and director of health, wellness, and performance. He refers to the yips as a progression: fight, flight, fear, frigid, frozen. "[My] NBA guys, they shoot 1,500 free throws in a practice," he tells me. "Bam, bam, bam! Nothing but net. But in a game, they’re missing three out of four. Fight-or-flight tells the brain, I'm scared. The fans are going to eat you alive, the court is gonna choke you. They’re conscious in a fearful way."

Dr. Hettiarachchi spent 17 years with the Wizards, including eight with the WNBA’s Washington Mystics, and can’t recall a single conversation about “the yips” within the organizations. (“It’s not even a word in the NBA.”) His first recollection of witnessing the yips came as an intern with the now-Washington Commanders—quarterbacks throwing 50-yard dimes in practice, only to struggle to throw 10-yard passes in games. At one point in our conversation, Dr. Hettiarachchi pauses. “I want to share a story,” he says.

A lifelong cricket player, the native Sri Lankan traveled to the United States to play in a recreational tournament. "I couldn’t pitch," he says. "I felt like I couldn’t let the ball go. I felt like the ball was so light—like I was not holding the ball. I’m like, Oh, my God. Then, I go home, I’m practicing, and I’m perfect. The next Sunday, I go to bowl in a game—at that moment of release, my brain was going back to [the past] and freezing. I put a monster in my own head because nothing happened in that game. The body can’t release. It’s a defensive mechanism.”

Dr. Hettiarachchi enrolled in grad school, and his schedule no longer allowed for cricket tournaments. A few years later, during a trip home to Sri Lanka, history repeated itself. He still couldn’t pitch in a game. “After that day, I haven’t really played cricket,” he says.

Magnuson carried physical pain into the game against Arizona. In its aftermath, he endured a level of emotional trauma that felt just as scarring. Over the next few days, Magnuson says he received relentless death threats on social media.

“Every single day, someone was sending me a different death threat or [suggesting] a different way for me to kill myself,” he tells me. “I got to see a really dark side of fan culture, and it just made me not want to be in the spotlight—to get away from anybody who knew me. I got off social media and haven't been back since.”

Magnuson's mention of social media reminded me of another psychologist I spoke to for this story: Dr. Armando González, affectionately known as Dr. Mondo, founder of Cheatcode and Cheatcode Foundation. “If you're worried about anything as an athlete, it's physically getting hurt. But the body is saying, ‘Screw that,'" he said. "Whether you're aware, there's this other tab open, and it's a protection mechanism to make sure that you emotionally don't get rejected—that Twitter doesn't blow up over what you do today. What's amazing about working with yips is that you often find that shame and embarrassment are, unsurprisingly, at the center."

Magnuson’s botched snap was an isolated incident in the sense that that was his final game action, but it may have been the culmination of a series of traumas pooling in his nervous system. Magnuson arrived at the 49ers’—and later, the Las Vegas Raiders’—facility every day petrified of getting cut. He had always been a confident, joyful football player. First, at La Costa Canyon High School in the San Diego suburb of Carlsbad, California, then as a four-year Michigan Wolverines standout. He was projected to go anywhere between the second and fifth round of the 2017 NFL Draft, but went undrafted with “no clarification” as to why he’d fallen.

“I felt like a failure,” he says. “I was what was called a bottom-of-the-roster player. Every single day, I was walking into the building with anxiety that I’m gonna get a call to go up to the general manager’s office because they’re gonna cut me. I had the fear of, This injury is gonna be the last one. Meaning, they wouldn’t want me anymore. I’d beat myself up. I was so critical of myself and took all that home with me and laid in bed and stressed for hours.”

Magnuson was in survival mode, leaving no time to process his anxiety, a tension that fed into his soft-tissue injuries. But Dr. Mondo knows what he’d have told Magnuson if he knew him then—what he tells every athlete who seeks him out for help.

This says nothing about your mental strength.

Don't let anyone tell you there's something wrong with you.

You're not making this happen.

Dr. Mondo first associated the yips with Chuck Knoblauch, a former MLB player. As a teenager in Sacramento, California, Dr. Mondo watched Knoblauch from afar, as he ascended to All-Star status with the Minnesota Twins, before unraveling after he was traded to the New York Yankees in 1998. Dr. Mondo chalked it up to Knoblauch wilting on the New York stage.

“It felt like the plague came over him," he says. "This really good baseball player can’t do the easiest thing that he used to be able to do in his sleep. As a kid [who played sports], I thought, I hope that doesn’t happen to me. That’s terrifying. There was so much ignorance.”

Dr. Mondo has spent his adult life working toward replacing that ignorance with education. He worked as a licensed marriage and family therapist in Sacramento, where he still resides, before attending a brainspotting training clinic hosted by Dr. Grand in early 2020. Brainspotting, as Dr. Grand often says, is a therapeutic technique rooted in the discovery that “where you look affects how you feel.”

Now, Dr. Mondo almost exclusively works with athletes, including those suffering from the yips. He’s entering his third year as a consultant to the Tennessee Titans, head coach Mike Vrabel sought him out. Dr. Mondo can’t quantify how many people he’s consulted with in Major League Baseball who, with tears in their eyes, curse the yips for prematurely ending their careers—a lingering wound that drove them to get into player development and personnel roles as a second act.

As then-Cowboys kicker Brett Maher missed four-straight extra points in that January game in Tampa Bay, Dr. Mondo saw the moment through the trained eyes he didn't have when watching Knoblauch decades earlier.

The worst thing in the world they could do is cut him, he thought.

I reached out to several current and former collegiate and professional athletes for this story, asking if they felt comfortable going on the record with experiences that they'd classify as the yips. All of them declined—except for Magnuson.

“Although advancements are happening, the sports world still has quite a bit of stigma around stuff like the yips,” says Dr. Mondo. “It requires a high-level understanding of neurophysiology to truly understand what's going on. Hopefully, the more people that share their stories, the more that'll change. But for now, it’s the fibromyalgia of the mental world. Like, We don't know what's going on with this player, so it must be mental. The message gets communicated to the player that we can’t help you. Players internalize the bleakness. We're still running an outdated story on what the yips are, the cause of the yips, and who gets them.”

In 2003, Dr. Grand discovered brainspotting when he was introduced to an ice skater who couldn’t land a triple loop—popping out of it after two turns, every single time—after landing it perfectly a million times. They worked together for a year with process and physical therapies, but it wasn’t until Dr. Grand keyed in on her eye positioning that she had a breakthrough.

“The eye position right next to her nose—she was looking at my fingers—her eye went into this intense wobble and freeze,” Dr. Grand says. “I just held my fingers there, and she was looking at it right in that spot, and all these traumas that had never come up before came out of her. She was watching them and narrating like a video. So many of the traumas we thought we had already processed came up and opened up again—and we processed through to a deeper level.”

Dr. Grand relays that the ice skater’s parents had divorced when she was young, and that formative trauma was compounded by several sports injuries. Brainspotting, he says, “brings to the surface unlimited and infinite developmental traumas” by exploring someone’s full visual field to identify fixed eye positions that allow access to the subcortical brain. "If you are focusing on something that is bothering you, it feels different when you look to your left or look to your right," Dr. Grand says. It all has to do with how synapses and neurology are connected to the nervous system. The method is incredibly complicated, but the results are often undeniable.

The following day, the ice skater called Dr. Grand to relay that she’d performed the triple loop without issue—and she never froze with the skill again. Dr. Grand has utilized brainspotting with at least 40 people suffering from the yips—from athletes to railroad engineers—but over 13,000 therapists, like Dr. Mondo, have been trained in the technique, multiplying the impact by hundreds. "It's a human being who does athletics at a high level," says Dr. Grand. It is always the human being. What we call the yips—performance inhibition or freeze—happens to human beings.”

As for Dr. Mondo, he utilizes brainspotting alongside other therapeutic techniques with individual professional athletes. Sometimes, their work together begins before they formally meet. "When I watch players now, I'm constantly looking for their facial reactions." he says. "I'm looking for tension in their shoulders. I'm looking for their reactions to tough moments. I would say there's a game within the game that David provided language to in a way that I never had. There's a deficit that's happening, and it seems to be showing in these poker cues, as David would call them. It informs much of how I can help someone even before the yips occur.”

Chicago Cubs shortstop Dansby Swanson approached Dr. Mondo after a disappointing 2019 campaign with the Atlanta Braves. With the help of brainspotting, Swanson identified the root of his conscious anxiety: the pressure he felt when going number-one overall to the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2015, only to be traded to his hometown Braves by that December. “Dansby didn’t get the yips,” Dr. Mondo says. “Of the baseball players I've worked with, the yips are still probably under 10 percent. But if you look at his process, it’s not dissimilar from what was happening to a player that eventually develops the yips—because he was progressively working up to that point where baseball no longer felt safe.”

As for football, Dr. Mondo has past experience with an NFL player who developed the habit of repeatedly drawing penalties from false starts—a more concealable version, like Magnuson's case. Meanwhile, Dr. Hastings treated a professional baseball player whose yips presented as “throwing very uncharacteristic balls into the dirt, or wildly off-target” following a trade. According to her, he was “experiencing a heightened awareness of being evaluated as he tried to prove himself.”

Through talk therapy, Hastings was able to link his intensified desire to impress his new team to the pressure a parent put on him around baseball throughout his adolescence. “The critical feedback outweighed the praise, and that became this athlete’s inner voice, so he had a hard time accepting himself and viewing mistakes as points of growth, instead immediately going back to, I suck. I can’t do this anymore,” she says.

Dr. Hastings incorporated relaxation exercises into the player’s daily routine and specifically “encouraged him to sit in a quiet place with a baseball every day for at least five minutes.” Within ten months, he returned to form. Dr. Hastings also runs a weekly “process group” for Rams on injured reserve, and she finds that a lot of players approach her to work through deep-rooted issues unrelated to football—unknowingly lessening the likelihood of a future yips outbreak.

“It’s about, ‘It’s not your fault. You have had these problems ingrained in your brain to where your neurons are firing differently, and so we need to invest the time to change those neurological patterns,’” she says, “That can only happen with time and repetition.”

As former San Francisco 49ers performance therapist Tom Zheng tells me, he'd prefer to retire “the yips” as a phrase. The rest of the psychologists I spoke to echoed the sentiment. It causes more harm than good—and as Dr. Hastings and Zheng relay, it’s already been informally banished within most athletic circles. Zheng sparsely heard players talk about the yips in San Francisco's locker room—even when they did, it was only as a joke. But forbidding a slang term out of superstition—or even fear—is far from phasing it out because the condition is understood by those who use it. Each doctor emphasizes that the latter can’t happen until empathetic language can replace sensationalism.

"If we update this encyclopedia and we actually create that knowledge within sports, it will have people in front offices feel more empowered in those moments and not be so quick to feel like they have to make [roster] decisions that might equate to giving up on people," Dr. Mondo says. "They would see it as similar to a lingering hamstring injury that might heal. And then, they'll convey the message to the players: 'Hey, this isn't a [death] sentence. Help is on the way.'”

As for Magnuson, he needed to leave the NFL behind to help himself. Shortly after retiring from the NFL, Magnuson saw a LinkedIn ad for therapy directed toward post-career professional athletes who suffered from anxiety. He immediately sought out a therapist, which allowed him to see it all clearly for the first time. Now 29 years old, he continues to attend group therapy via Zoom with former NFL players living around the country.

Magnuson imagines an idyllic future where this sort of collective healing isn’t put on hold until retirement—and perhaps, we as a society are closer to that than we give ourselves credit for. Regardless, Magnuson is at peace with not being able to apply his evolved mindset as a player. He found a way to make a more profound impact. Since last year, Magnuson has served as the offensive coordinator and offensive line coach at his alma mater, La Costa Canyon.

“High school kids are some of the most anxious kids, especially in sports, and they put the biggest pressures on themselves,” he says. “It is really interesting because I'm able to see it from such a young age and help kids understand it, see it, and recognize it, at least, even if they're not willing to get help for it.”

Every Friday night, Magnuson sees anxiety grabs onto his players and tries to free them with breathing techniques he’s learned over the years. He sees young athletes who still have what he wasn’t afforded: time. Most importantly, Magnuson meets each of them where they're at—and treats them the way he desperately needed to be treated five years ago.

"I have a lot of knowledge and experience that I felt like I would waste if I didn't give it back to the game somehow," he says. "It's the lifecycle of a player: Once you're done, you help out the next generation. I like to tell the kids, ‘You're great. Just believe it.’"

You Might Also Like