Positive signs for MLB attendance? Early 2023 returns show winning is still a foolproof plan

It is still early enough in the Major League Baseball season that a surprise team might still emerge, that a young player could captivate a fan base, or that grand plans could very much go sour – all affecting whether a paying customer is compelled to get off the couch for a night at the ballpark.

Yet a month of baseball is almost always a significant enough tell to forecast which franchises are healthier at the gate – and preliminary signs indicate MLB might be standing firm against decades of loss capped by a stadium-shutting pandemic.

With at least six and up to 16 home games for every team in the books, and with baseball’s most poorly attended games typically coming in the dregs of April, a majority of clubs have drawn more fans to their lowest-attended game – an imperfect but telling metric for a club’s season-ticket base – than they did a year ago.

The numbers are even more encouraging for teams on a competitive upswing since 2019, when leaguewide attendance dropped by 1 million as four teams lost 100 games, many more franchises continued a pattern of non-competitiveness and modern challenges of the attention economy grew.

And then the pandemic hit.

No fans were allowed at games in 2020, followed by a gradual reopening in 2021 and then a mess of MLB’s own making: The 2022 lockout, which froze the industry for 99 days in the spring and delayed Opening Day by a week.

Sure, a pitch clock and other new rules meant to stimulate action mean 2023 won’t be “normal” in its own way, either. Yet there’s also no direct forces holding it back, and effects of the new rules may not truly be felt for years. And through a month, the leaguewide average of 27,267, per Baseball-Reference, is up slightly over 2022’s 26,566 – an encouraging sign given the summer that still awaits.

With that, an examination of April attendance – and what it may mean for individual franchises and the league at large:

Gainers and losers

While early May and September can also be sinkholes for individual dates – and thus affect the complexion of this list – the worst is likely over for almost every team. And most have made at least modest gains on their worst nights of the year:

– Teams for which lowest-attended game is up from 2022 (16): Rays (57%), Mariners (52%), Yankees (41%), Phillies (43%), Marlins (33%), Blue Jays (28%), Astros (23%), Mets (23%), A’s (22%), Pirates (20%), Padres (17%), Dodgers (13%), Guardians (11%), Cardinals (12%), Cubs (7%), Giants (5%).

– Teams for which lowest-attended game is flat (2% or less) year over year (3): Diamondbacks, Twins, Rangers (up a whole five humans, to 15,867).

– Team for which lowest-attended game is down year over year (11): Orioles (21%), Reds (20%), Red Sox (15%), White Sox (10%), Rockies (10%), Royals (12%), Brewers (12%), Angels (10%), Nationals (8%), Braves (7%), Tigers (4%).

The trends are somewhat predictable: Seven of the eight and 11 of the 14 biggest gainers made the playoffs last season, with the Rays also enjoying a 20-3 start and a 14-0 mark at home. The Marlins, A’s and Pirates’ attendances were so low that an early hiccup is enough to land them on the positive list.

And perhaps the most interesting club is the Yankees, who are showing the value of re-signing a superstar who hit a record 62 home runs in a year the club made the American League Championship Series. Not only is the Yankees’ worst crowd of 35,392 more than 10,000 greater than last year’s, they’ve already absorbed 16 home dates, most (along with Seattle) of any club.

It should be a crowded summer in the Bronx.

From the last 'normal year’ to now

Thanks to the pandemic and lockout, data from recent years remains tricky to compare. Yet comparisons to 2019 – or, the last "normal year” before the pandemic – can be instructive.

Keep in mind that 2019 already marked a low point for MLB attendance. The league’s loss of more than 1 million fans at the gate capped a trend that saw it lose 11 million fans since 2007, when attendance peaked at 79.5 million. A new paradigm in how fans attend games and how clubs construct new stadiums was already taking hold.

Yet the four years since illustrate that proven sports business practices – i.e., fielding a decent and charismatic team – still matters.

Take the Boston Red Sox. In 2019, they were reaping the post-World Series benefits at the gate, but by September were firing their general manager, Dave Dombrowski. They traded franchise icon Mookie Betts in February 2020, followed by a last-place pandemic season. A surprise run to the 2021 ALCS followed, but another last-place finish preceded the December 2022 departure of another star, Xander Bogaerts.

The Red Sox proudly touted a 10-year sellout streak, from May 2003 to April 2013. Yet their new reality indicates their floor is down 27% (33,664 to 24,477) from their worst April 2019 crowd.

Fan discontent seems evident in Anaheim, too, where the Angels are down 37% (28,571 to 17,780). Since April 2019, the club has endured the tragic death of pitcher Tyler Skaggs, a failed effort to strike a deal for a new stadium and owner Arte Moreno placing the club on the market -only to take it off.

All the while, the club has extended its playoff-less streak to nearly a decade even as Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani cement their status as generational performers. That’s perhaps the most startling aspect: Since Ohtani’s 2021 MVP season, he has been appointment viewing at least once a homestand, when he pitches, and provides the promise of something spectacular almost every evening.

Yet the headwinds of organizational dysfunction have proven too strong.

The news is correspondingly cheerier for clubs on the upswing.

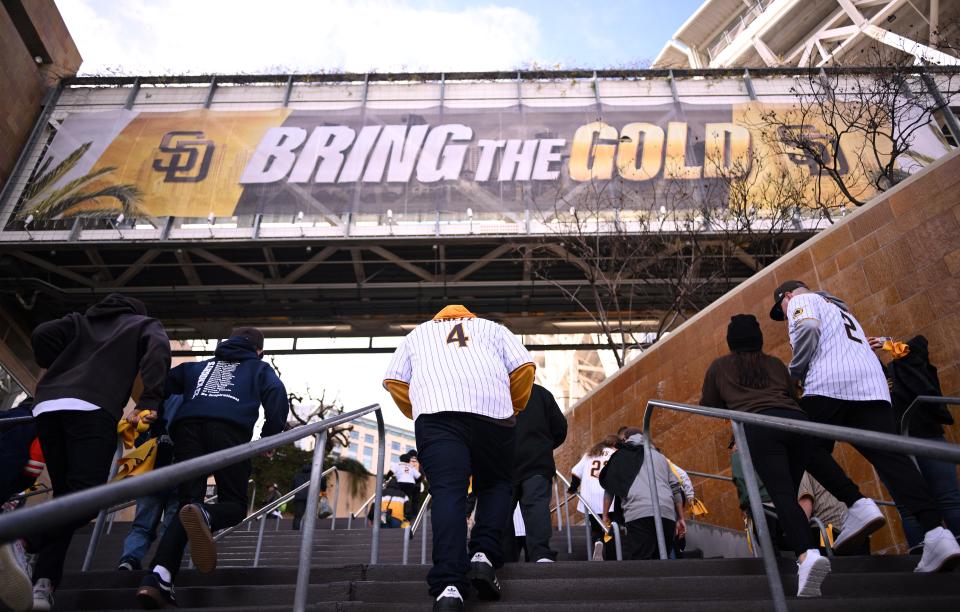

In April 2019, the Padres had freshly inked Manny Machado to a $300 million contract, trotted out a rookie named Fernando Tatis Jr. and staked a claim to relevance. Then, they came roaring out of the pandemic, trading for pitchers Yu Darvish and Blake Snell, adding Juan Soto in 2022 and then stealing Bogaerts from the Red Sox.

The payoff is evident: San Diego’s worst crowd in the first Machado-Tatis April was 18,683; this year, it is 29,581, a 58% increase; the Padres have drawn at least 40,000 for nine of their 13 home dates.

It’s the same story in Toronto, where the Blue Jays bottomed out with a crowd of 10,460 in early April 2019, as budding star Vlad Guerrero Jr. was held down in the minors to harvest an extra year of service. He was recalled later that month and the club has built significantly around him, winning at least 90 games each of the past two seasons.

And they are reaping the benefits at a renovated Rogers Centre, where the season low of 26,192 marks a 150% increase from those quiet days of April 2019.

Hopeful, helpless at the bottom

Forgive an Oakland A’s fan if they’ve forgotten all about 2019.

The A’s won 97 games, made their second of three consecutive playoff appearances and boasted a trove of current and future All-Stars: Matt Olson, Matt Chapman, Chris Bassitt, Liam Hendriks, Sean Murphy.

All are gone. And the A’s may soon be, too.

While any team might view a crowd count in the four figures as an embarrassment, let’s just say the A’s are showing the impact of franchise dereliction and threats of relocation. Their worst crowd has dropped 62% from April 2019, a fall from 8,073 to 3,035 as a fan base girds for a potential move to Las Vegas.

Oakland and Tampa Bay have long been the caboose in MLB’s facility game, each aiming for a modern park and, in doing so, partially discouraging fans from attending the current one (It’s hard to tout the need for new digs without ripping the current one).

Yet a new facility is no guarantee – nor does an old one have to be a sentence to purgatory.

The Miami Marlins are proof of both – they’ve long joined the A’s and Rays at the bottom of attendance rankings despite a gleaming park in Little Havana that opened in 2012 thanks to a bushel of public money. Yet the Marlins are showing signs of life: While their low crowd is still an underwhelming 8,272, it represents a 37% increase from 2019, when a gathering of 5,934 represented the low point.

In St. Petersburg, meanwhile, the Rays seem to be connecting with their base even as they scour both sides of the bay for a new home. Fourteen games into their Tropicana Field slate, the Rays have yet to lose – and yet to draw a crowd of less than 10,000.

For now, that’s a 57% jump from last year’s low point over a similar stretch and a milestone worth noting. After all, in 2019 they drew 22 crowds of less than 10,000, with a low of 5,786.

Sure, a four-figure crowd is almost inevitable – the season is too long and the Rays (probably) won’t win ‘em all. But after four consecutive playoff runs – the most prosperous stretch in franchise history – the locals may be responding.

And winning is a nearly foolproof business plan – under any conditions.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: MLB attendance for 2023 shows winning is still a foolproof plan