Opinion: Eric Dickerson's ailments are grim reminder of NFL glory's heavy bodily toll

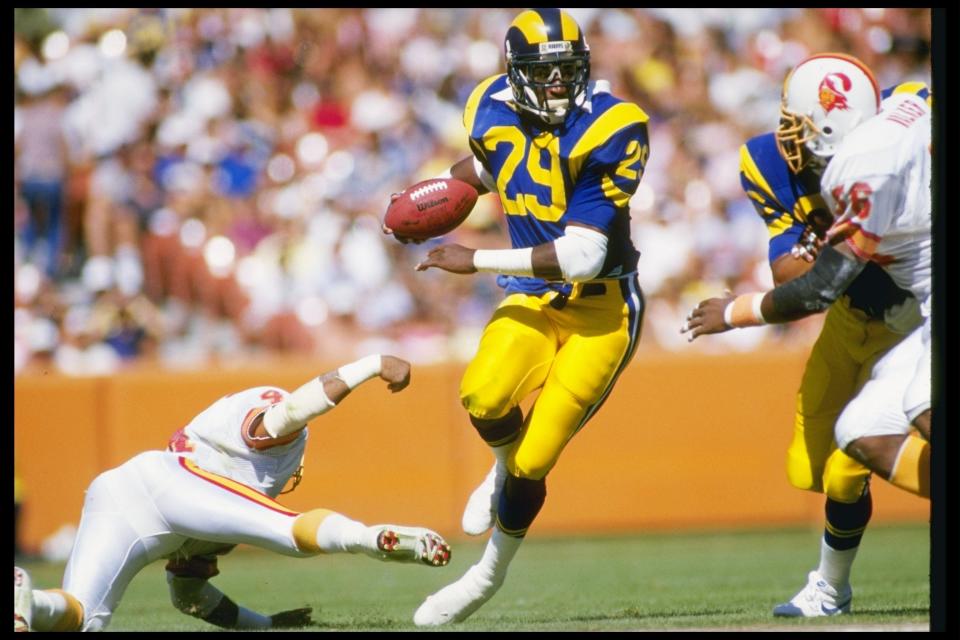

During his heyday, Eric Dickerson was one of the NFL’s most lethal running backs, a mass of speed, power, grace, guile, grit and tremendous production. He looked cool, too, capable of going the distance on any given snap as he peered from his Rec Specs, padded up with a neck collar while rocking a Jheri curl.

Now the owner of the NFL’s single-season rushing record just wants to get a good night’s sleep.

It’s the pain. In the neck. Or back. Or head. Or shoulder. Or toe. Or any combination thereof.

“Man, my sleep is messed up,” Dickerson, 61, told USA TODAY Sports from his home in Calabasas, California, during a wide-ranging phone interview. “The best sleep I’ve had in the last three years was when we went to London in 2019. I slept on the plane. I went, ‘Damn! Why can’t I sleep like that at home?’ "

The lack of sleep and assorted issues provide Dickerson with constant reminders of the toll he paid with his body to produce his remarkable, Hall of Fame career. It’s striking to assess the personal costs against the backdrop of football’s biggest annual celebration, set to be staged for the first time in 29 years in the Los Angeles area with Super Bowl 56 LVI.

Beyond the glitz, hype and glory that surrounds the NFL’s product, there’s this contrasting snapshot: so many retired men like Dickerson, dealing with scars and long-term effects from playing the sport in which, yes, they willingly chose to participate.

"People say, ‘You know what you were getting yourself into.’ You really don’t," Dickerson said. "You’re a kid. You take the abuse and move on. You just play. You’re a warrior.

"Ours is a slow death, declining in health. You watch so many players…and the sad thing is that the wives are the ones, or the girlfriends, who are stuck to pick up the pieces. That’s why I wish they’d do better by NFL players, with healthcare and the pension.”

Knowing what he knows now about the risks and lingering impact, Dickerson maintains he has no regrets, that he would still pursue a football career. He also won’t discourage his 9-year-old son, Dallis – “People tell me that he’s going to be a better athlete than me,” Dickerson said – from someday playing tackle football.

But he knows. The turf toe injury that nearly derailed his trek to the record 2,105 rushing yards in 1984 still haunts him. And that’s just one issue.

NFL NEWSLETTER: Sign up now to get exclusive content sent to your inbox

SUPER BOWL: The 56 greatest players in game's storied history

BEST MOMENTS: What are Super Bowl's all-time greatest plays?

During his entire football career, including the years with the “Pony Express” at Southern Methodist University, Dickerson maintains that he had two or three “confirmed” concussions. But he suspects he suffered many more, especially given advances in the research and treatment of head injuries.

Dickerson described being “knocked woozy” routinely, typically from helmet-to-helmet hits.

How many times did that happen?

“I have no idea,” he said. “So many times I couldn’t put a number on it. When I see guys (in today’s game) get hit and go inside the medical tent, I think if that had been there when I played, I might have never finished a season.”

Dickerson, who recently released a stirring autobiography, "Watch My Smoke," suspects he could suffer from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the neurodegenerative brain disease linked to repeated blows the head. Doctors are unable to confirm CTE in living patients, which is one reason Dickerson said he “probably would” donate his brain to science.

As it stands, he suspects he is living with CTE symptoms, which can include mood swings and outburst, and that the brain damage is a carryover from playing football.

“I know I do,” he said. “It’s no doubt. That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to write this book now. If it’s later, I don’t know if I would remember some of this stuff. I probably won’t, because of the hits. You can just tell. I talk to other guys about it. We know.”

Dickerson said the sleep problems he has encountered are typical among retired players from his era. Are they related to concussions?

“I can’t say for sure,” Dickerson said. “I can’t say for 100%, but I would be willing to bet, because I can’t sleep at all.”

Dickerson recalled a conversation from more than 20 years ago with O.J. Simpson. The topic was aging, and it came with a warning from Simpson: You’ll really feel the hits at 50.

“True. He was right,” said Dickerson, who played 11 NFL seasons, retiring at 33 following the 1993 season after doctors warned him of risks associated with a neck injury. “Back in my 30s and 40s, I felt good, body-wise. You get to 50, those hits really do come back. And you remember exactly where you got hit.”

He’s never forgotten the cheap shot absorbed in the end zone after scoring a touchdown against the New York Jets, when a defender blasted him in the chest.

“It was like 20 years later when it stopped hurting,” Dickerson said. “I could feel that exact spot. I have a keloid there. He cut me.”

Dickerson, of course, is supremely qualified to share insight with today’s generation of players. His credentials include four NFL rushing crowns and 13,259 career rushing yards, which ranks ninth all-time. His rookie record of 1,808 yards has stood since 1983.

Dickerson hasn’t been shy about lending his voice to the cause of increasing the pension and healthcare benefits of former players. There were increases for retirees in the collective bargaining agreement struck in 2020, but Dickerson and others bemoan them as hardly enough – especially when compared to benefits received by former players from Major League Baseball and the NBA.

Dickerson realizes he’s better positioned than many older NFL retirees. A conversation from the early 2000s with another Rams legend, Deacon Jones, still resonates. He said Jones told him that his monthly pension check was $250.

“I was blown away by that,” said Dickerson, mindful of the historic imprint left by Jones. “If you helped Apple get off the ground, you’d be taken care of. I’m not saying the NFL needs to pay us millions of dollars. But make it respectful, something you can be proud of.”

That’s just one of the topics Dickerson addresses in his book, which is rich in depth and substance. He doesn’t hold back in revealing so many professional and personal situations that formulated on a journey that began in Sealy, Texas, including upbringing provided by his adoptive parents, Viola, his natural great-great aunt, and Kary Dickerson, who passed away when Eric was 17.

“Some of that stuff really was therapeutic,” Dickerson said. “Talking about my mom, my dad, my grandfather, some of the time while talking about it, I broke down and started crying. My dad’s been dead since I was 17, but that was the best man I knew.”

Dickerson surely reveals a sensitive side in telling his story.

It’s also true he has some loyalty attached to the Rams – a franchise with which he bickered over contract matters until he was traded to the Indianapolis Colts. Yet since the team moved back to L.A. in 2016, he has supported it in a community service role.

And he sounds like a proud uncle when considering that the Rams pulled off the mission to play in the first Super Bowl in LA in 29 years, facing the Cincinnati Bengals.

“I’m very impressed,” he said. “I’m more impressed with how they’ve done it. I’ve got to give (general manager) Les Snead a lot of credit for going out and getting the big-time players they brought in and (Rams owner) Stan Kroenke, he signed off on it. …But I’m not shocked that we are here. We have all the right pieces in place. Now let’s just finish the job.”

Follow USA TODAY Sports' Jarrett Bell on Twitter @JarrettBell.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Eric Dickerson's injuries are grim reminder of NFL's bodily toll