Cincinnati family traces connection to first Kentucky Derby winner

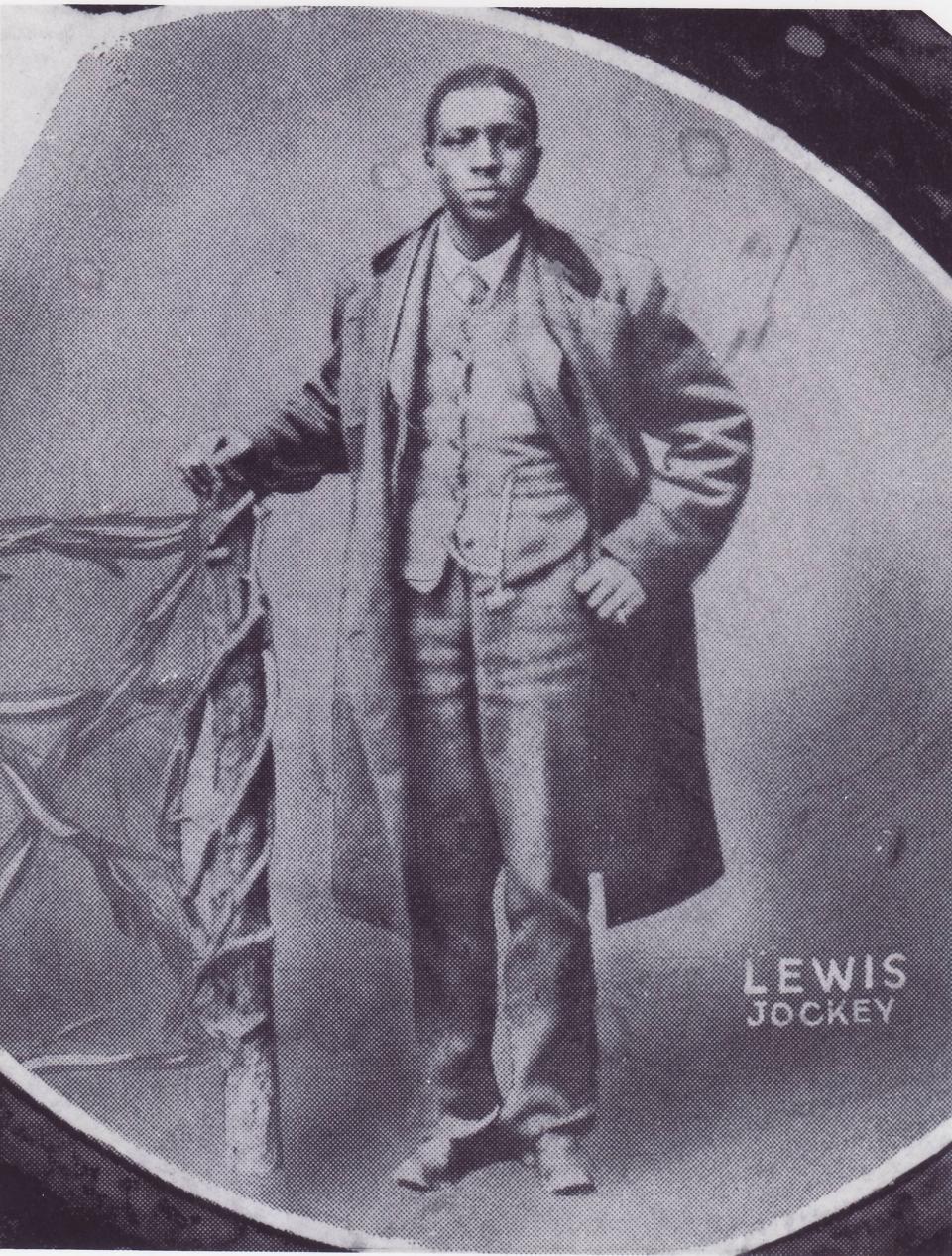

Oliver Lewis wasn't supposed to win the first Kentucky Derby.

The jockey atop Aristides was instructed to have the horse serve as a "rabbit" and go hard at the beginning of the race to wear down the field, so stablemate Chesapeake could preserve his energy for the end to ride to victory.

H. Price McGrath, the horses' owner, did not consider Aristides the superior of the two horses.

But, with only the dirt track in front of them, Oliver Lewis raced Aristides down the stretch.

The chestnut colt was forcing a daunting pace. Lewis glanced toward the rail where McGrath raised his hand and motioned to Lewis to go for the win.

“Go on,” McGrath shouted.

In a green silk with a diagonal orange stripe, Lewis and the little red colt took off.

∎ ∎ ∎

It was a Monday in May, 150 years ago. The second race of the day at the Louisville Jockey Club, which would later become Churchill Downs, was underway. More than 10,000 spectators gathered to see the 15-horse field in the 1 1/2-mile race for 3-year-old thoroughbreds.

According to accounts of the day published by The Courier Journal, "Chesapeake, who is a vicious starter" was one of the last to leave the start line.

Rounding the first turn, Lewis positioned Aristides in second with “the rest of the bunch close behind them.”

Lewis, weighing 100 pounds, pulled on Aristides’ reins, attempting to slow him so Chesapeake could take over, but the “Little Red Hoss” refused to cooperate. He wanted to run.

“The others seemed to be outpaced. For Aristides was cutting out the running at an awful speed,” the article recounted.

At the half-mile pole, Lewis continued to work to slow the colt, “expecting Chesapeake to come up and take up the running.”

"But where, oh where was Chesapeake, but way back in the ruck and not able to do anything for his stable," the article read.

Down the stretch, Lewis saw McGrath taking in the positions of the horses. Then he saw McGrath wave them on.

Lewis loosened his pull on the bridle.

Aristides, son of Leamington and Sarong, “dashed under the wire the winner of one of the fastest and hardest run races ever seen on a track.”

With a time of 2:37 ¾, the thoroughbred and his 18-year-old jockey made history.

At the time, no one knew it would mark the start of 150 years of Louisville's most treasured event.

During the lead-up to this year’s historic Run for the Roses, The Courier Journal talked with gambling experts, librarians and historians — with resources from Kenton and Cincinnati public libraries; the Keeneland Library; The Filson Historical Society; the Cincinnati Museum Center; and African Cemetery No. 2. — to uncover the history of the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby.

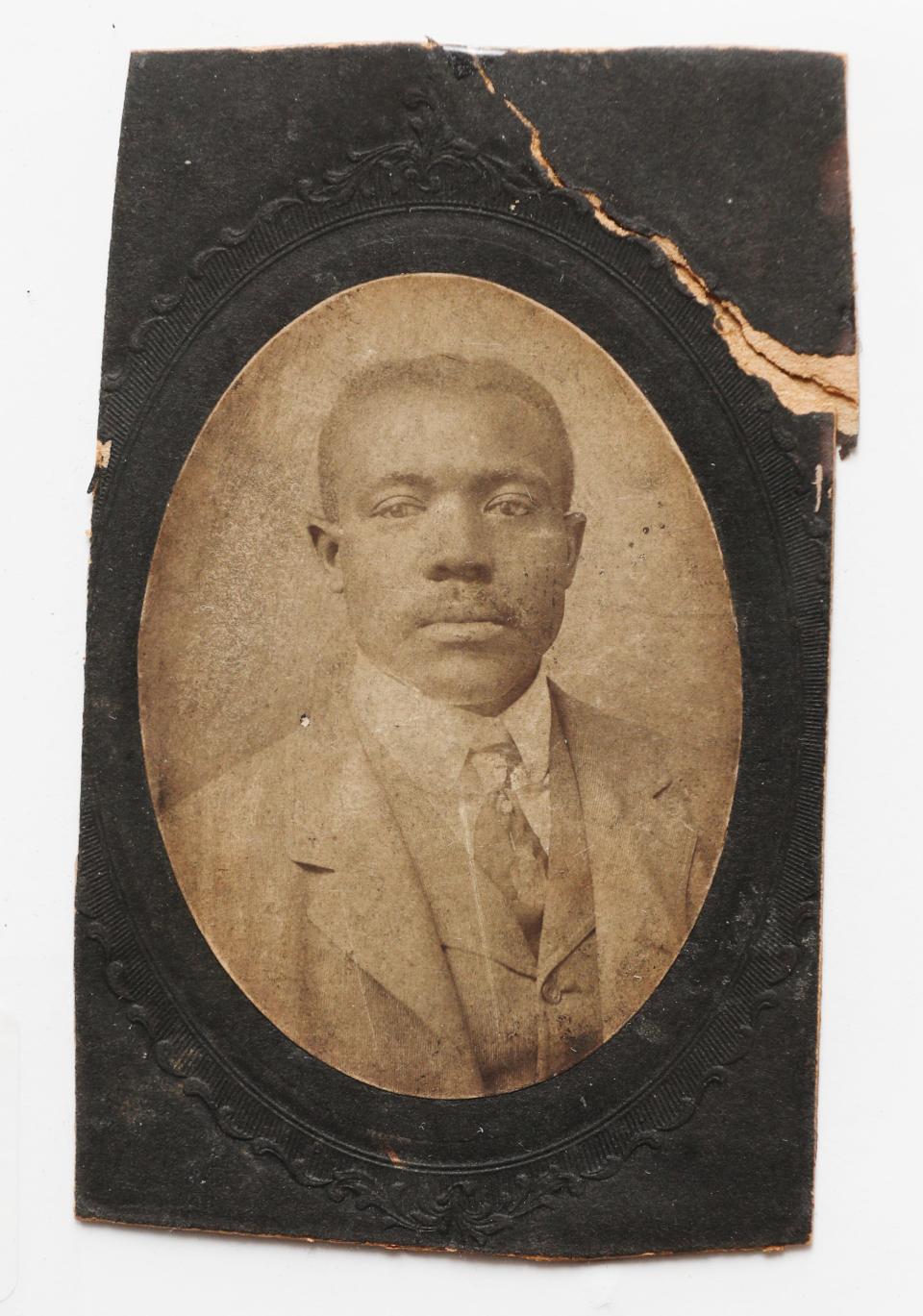

While other Kentucky Derby-winning jockeys have paragraphs in programs and at museums, Lewis' history was mostly two short lines: He was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby. He became a bookie (then a legal profession) who created the modern-day racing form, a record of a horse’s performance.

This is the history of Oliver Lewis that has never been fully told:

A legacy lost to time

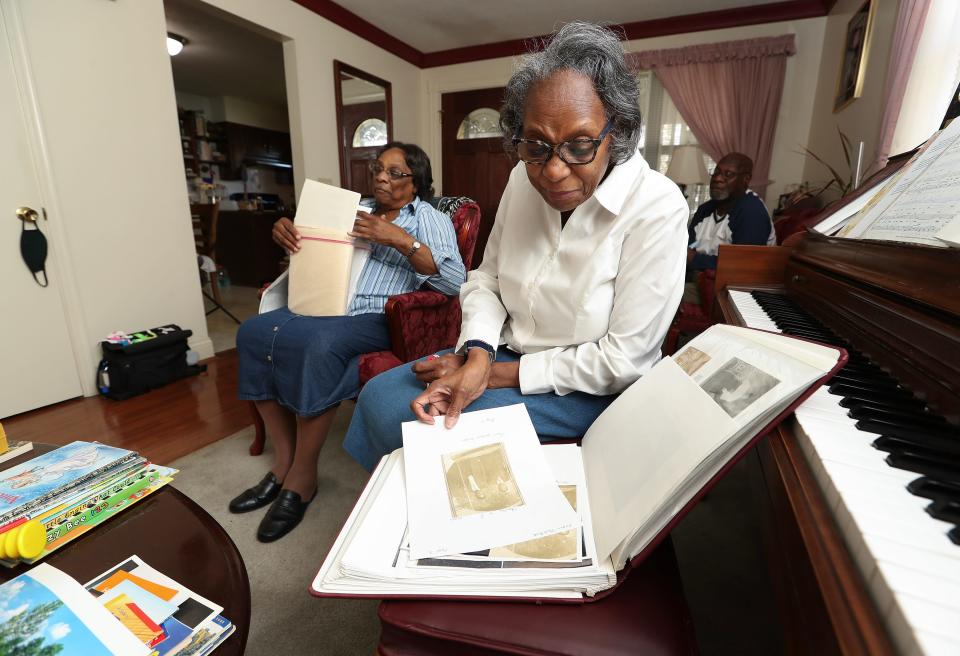

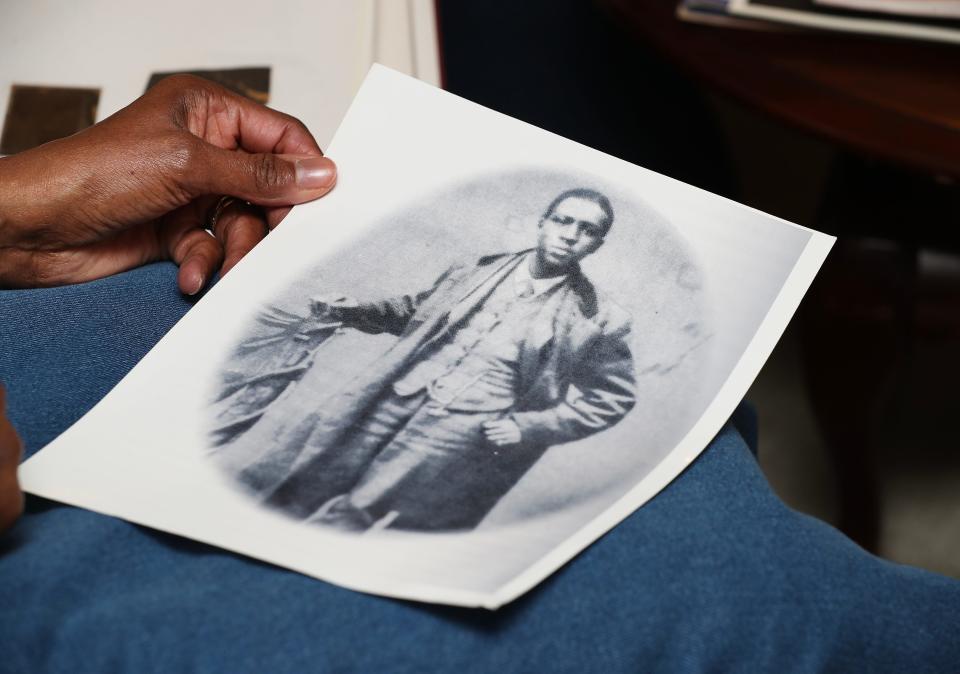

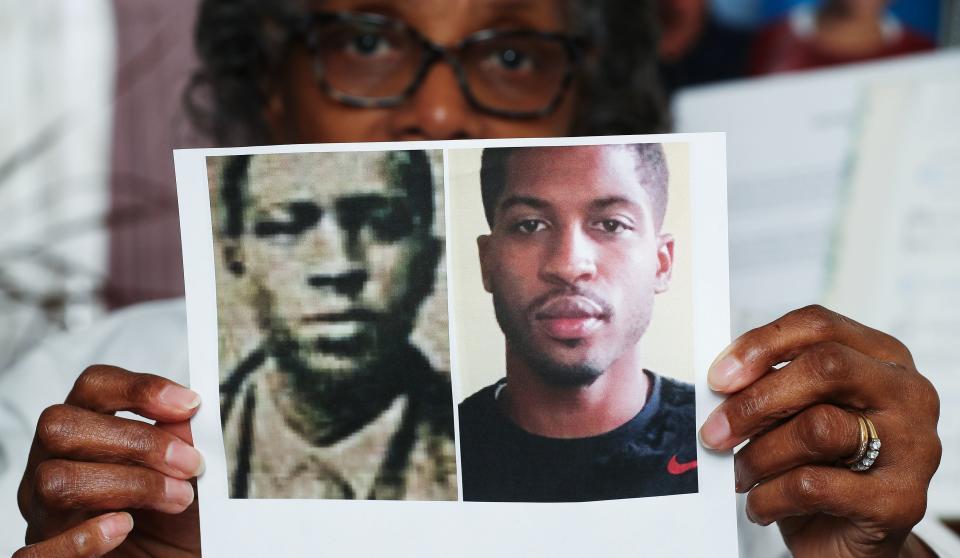

Ruth Johnson-Watts nestled into a high-back chair in her Cincinnati home in March with a gallon-sized Ziploc bag bulging with records.

Her younger sister, Gladys, sat on a piano bench, a century-old photo album in her lap.

Her brothers, David and Louis, were telling stories of their childhood.

They are four of seven living great-grandchildren of Oliver Lewis — that we know of. For the last 40 years, Ruth has been trying to piece together the family's history.

What were the stories they heard about the Kentucky Derby growing up?

“We didn’t hear any,” Gladys said.

“That’s the amazing part about it,” Ruth said.

“I even got his name,” Louis said with a shrug.

At some point, historians say Lewis became a bookie, and although it’s a legal occupation, not all in the family wanted it repeated, including their parents.

"They were in the church," Ruth said. "So, gambling and horse racing and stuff like that, they didn’t talk about it."

It wasn’t until a call from a Kentucky State University professor in 2013 that they fully connected their lineage to the first Kentucky Derby winner through his 1924 Lexington death certificate and a 1958 obituary in the Cincinnati Enquirer for Lewis’ wife.

Ruth ruffled through more papers.

There are lots of questions to ask.

“Well, hopefully, I have a lot of answers,” Ruth said.

She began to pull out state census records and city directories.

Who was Oliver Lewis?

Oliver Lewis was born into slavery in Woodford County in December 1856.

He is the first of three Oliver Lewises documented as being born in the Lexington area in a five-year time span, so figuring out what he did versus the other two Oliver Lewises has been a challenge.

On Feb. 26, 1865, when Lewis was 8, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people in the Confederate states. But Kentucky, a union state, voted against the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment (until 1976). It’s not known when Lewis was considered free.

A Woodford County census from 1870 lists 14-year-old Lewis, his parents and seven siblings, at a Versailles farm. He could not read or write. He worked as a farmhand. Historians aren't exactly sure which farm.

Could it be the same Versailles farm where Aristides was foaled in 1872? That farm was owned by Henry Price McGrath, known in historical records as H. Price or Price McGrath.

Possibly.

Born in 1813 or 1814 in Jessamine or Woodford County (accounts on this vary), McGrath’s life history is a bit more documented than Lewis'.

Born to poor parents, McGrath learned to be a tailor, like his father, but grew tired of its monotony. He became adept at card games, especially poker. Determined to put his skills into practice, McGrath went to New Orleans. In 1852, he opened a gambling house.

It became known as the “finest in the South,” according to many newspaper accounts.

In 1863, he went to New York to open a "faro bank", a French gambling card game, on 23rd Street. Known as a heavy bettor, he once told friends he won $45,000 on a single game of Boston, an 18th-century card game.

He returned to Lexington and bought 500 acres of the finest bluegrass. He called it McGrathiana.

“Where Oliver was working for McGrath,” Ruth explained.

Then came that fateful day in May 1875. Lewis would win two more races that season at the track in Louisville, including a second place on Calvin, another horse owned by McGrath.

But that victory at the Kentucky Derby wouldn't be the only time Lewis and Aristides went for a win.

Lewis and Aristides compete at Belmont

On a breezy June day in New York, a month after the Derby victory, McGrath entered three of his 3-year-old thoroughbreds — Chesapeake, Aristides and Calvin — into the second race of the day, a mile-and-a-half race called the Belmont Stakes.

Lewis was once again aboard Aristides. He directed the horse toward the start line, down into the woods. After six false starts, the starter finally dropped his flag on a clean start as the spectators shouted, “They are off.”

McGrath's game plan was again for the little red colt to serve as a rabbit for his stablemates.

In the book "The Great Black Jockeys" by Edward Hotaling, he writes, “This time, knowing his colt, Lewis pulled even harder than he had in the Derby, — pulled and pulled, in fact, until the crowd finally shouted, 'Let go that horse’s head!'

"Lewis didn’t let go though."

Calvin, with jockey Bobby Swim aboard, won the Belmont Stakes. Lewis and Aristides finished second.

“Reports came in that Calvin had beaten both his stable companions in a severe trial and that McGrath had backed him to win in large amounts,” said an article in the New York Times that ran the next day. “McGrath could have won with Aristides with equal certainty ...”

Aristides went on to have a champion year, winning the one-mile Withers Stakes at Jerome Park and the two-mile Jerome Stakes at Aqueduct.

Both times, McGrath picked Bobby Swim to be Aristides' jockey.

In 1875, the editor of a sporting paper called out McGrath for gambling on his horses, claiming he had "the best stable in America, ran his horses victoriously, all the fore part of the season" only to "lose in order to rake in the odd" at the end of the season.

It claimed McGrath weighted Aristides down, so he could bet against the colt to win "enormous sums of money."

By August 1875, newspapers list that McGrath had won about $50,000 on his horses' victories.

The jockey that became a trainer

The first census taken after the Derby victory, in 1880, does list Oliver Lewis, then 22, as a servant who “breaks horses,” or trains them, at McGrath’s Versailles farm. (Today the farm is the University of Kentucky's Coldstream Research Campus.)

A bachelor, McGrath would throw pre-meet parties and ask Lewis and other farmhands to bring up the horses for his guests to view.

On April 7, 1881, Lewis would marry Lucy Wright.

The marriage certificate listed him as “a writer,” Ruth said. “Instead of a rider.”

Three months later, McGrath, “the most prominent American turfman of the time” died before races in Long Branch, New Jersey.

Not a single obituary mentioned his Kentucky Derby victory six years prior. At the time, it wasn’t yet considered the the "fastest two minutes in sports."

Although he continued to be listed as a jockey who rode in races from Chicago to Covington to Newport, Lewis also began to train horses more.

Before the start of the fall meet in 1889 at Churchill, trainers were returning to their stables. A newspaper account listed them one-by-one — the last was Oliver Lewis.

Following McGrath's death, Aristides was moved to a farm in Indiana, then later sold to a farm outside St. Louis.

The little red colt died on June 21, 1893.

In an obituary for Aristides written in The Kansas City Star, the final line mentioned the Derby-winning jockey.

Lewis was training a horse named Reputation for St. Louis bookie Sam May.

The history among us

There are records of an Oliver Lewis living in St. Louis at the exact same time. He owned a bar called The Turf Station.

There aren’t enough records to indicate if that’s the Kentucky Derby-winning Oliver Lewis.

By 1899, a newspaper account mentioned Lewis as Sam May’s scout, bringing him information on the horses.

Lewis' compilation of that data, including detailed handicapping "served as precursors to those found today in publications such as the Daily Racing Form," according to the Kentucky Derby Museum.

"It would take a lot of information and a lot of connections," David G. Schwartz, a University of Nevada, Las Vegas professor and author of "Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling," said of Lewis' work. "It's a real testament to his drive, for sure."

At the same time, despite wining 15 of the first 27 Derbys, Black jockeys were being pushed from the industry. Jimmy Winkfield was the last Black jockey to win a Kentucky Derby. That was 1902.

“In 1904, he’s living in Cincinnati,” Ruth says as she runs her finger across a city directory. “He’s listed as a laborer.”

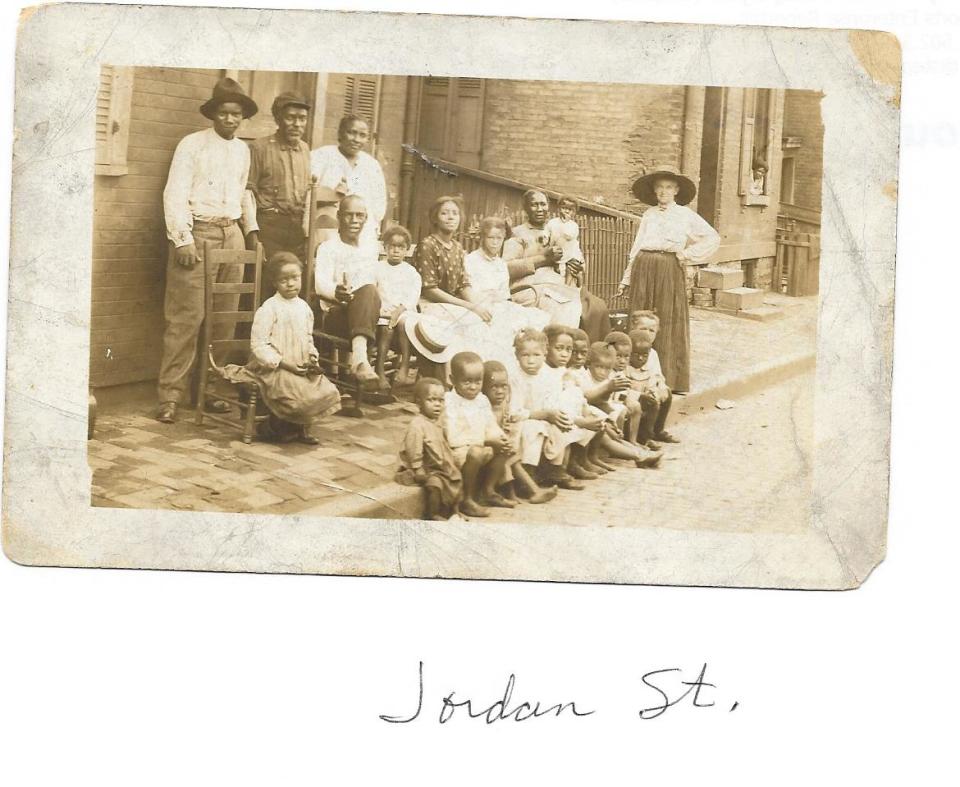

Like many parts of his life history, Lewis’ home off Jordan Alley in Cincinnati's historic West End is gone. It was bulldozed during a 1950s urban renewal project that remains the largest displacement of families in American history.

While watching races at Latonia, a since-defunct track in Northern Kentucky, 30 years after his Derby victory, The Cincinnati Post quoted Lewis as saying: “The jockeys of today are poor judges of pace. They try to make every post a winning one, so by the time they reach the stretch run, their mounts are all out…”

When he died in 1924, he was buried alongside his mother in Lexington's African Cemetery No. 2, located 80 miles east of Churchill Downs.

Mark Coyne, cemetery groundskeeper, and cemetery historian Yvonne Giles have spent decades searching for what was almost lost when in 1970, the city took control of African Cemetery No. 2 and wanted to disinter the thousands buried. The city hoped to develop it. Giles and others fought back.

Through Giles' research, they've learned the eight-acre plot holds 1,000 markers and thousands of unmarked graves, for at least 7,600 African Americans, in all.

Today, Lewis is one of at least 186 African Americans crucial to the early days of the horse racing industry buried in the historic cemetery, along with Kentucky Derby-winning jockeys James “Soup" Perkins and Isaac Murphy, and Derby-winning trainer Abraham Perry.

“That’s in the order of about 5% of people buried here had something to do with the horse racing industry in Kentucky,” Coyne said.

Lewis' legacy lives on

One by one, Louis and David and Gladys said goodbye to Ruth.

She was searching through another box of documents.

For so long, there was Kentucky history they didn't know their great-great-grandfather wrote.

A week before the 150th running of the legendary race, Lewis' family will visit Churchill Downs for the first time, for the unveiling of original life-sized art of Oliver Lewis and other Black jockeys during a private event held by artist Eugene Poole Jr. at the Kentucky Derby Museum.

A T-shirt design of Lewis, funded and printed by African Cemetery No. 2, will be sold during a special Pre-Derby tour of the cemetery on April 27. There are also plans for Old Hillside Bourbon Co. to produce a limited-edition commemorative bottle in honor of Lewis that will be available for online purchase in the coming weeks.

But before they leave Louisville's most hallowed grounds, Lewis' family hopes to sneak a peek at the dirt where a little red colt and a young Black jockey won a race they were never supposed to win.

Stephanie Kuzydym is an enterprise and investigative reporter. She can be reached at skuzydym@courier-journal.com. Follow her at @stephkuzy.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Oliver Lewis won the first Kentucky Derby. His story doesn't end there