The fight for Joe Paterno's legacy isn't over

STATE COLLEGE, Pa. — The statue no longer stands there, so he did instead.

Franco Harris took his place on the grassy hill where Joe Paterno’s statue once stood at 9:45 here on Saturday morning. He remained there for nearly two hours leading up to Penn State’s game against Temple, posing for photos and thanking fans “for standing with us.”

At one point, the Nittany Lions and Steelers legend pulled out a yellow piece of paper and read a prepared speech.

“The powers that be can destroy our wall,” he said, “but they will never destroy our bond and our love of the program and our love for our coaches and our fellow players.

“We will stand up to the lies.”

At one point, fans around him started chanting, “Success with honor!”

The wall Harris mentioned once stood behind the statue of Paterno, the longtime Penn State football coach. Both the statue and the wall were removed in 2012 in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal.

Harris believes the players have been unnecessarily blamed for the Sandusky tragedy, and he wants the wall bearing the players’ likeness back.

He also feels Paterno was unjustly blamed.

“We hope that one day Joe’s statue will once again be with us,” Harris told the crowd. “So whatever Sue [Paterno] decides, we stand with her and her family.”

At the end of his speech, Harris picked up a brick – a symbolic token of an effort to rebuild a wall and a late coach’s reputation.

“In one way or another, Joe Paterno had an impact on all of our lives,” he said. “As I lay down this brick, it is a testament to the culture that Joe laid down for us.”

Then he folded his piece of paper back up, put it into his shirt pocket, and spoke with every fan who wanted a word with him. One drove from Wisconsin, saying he hadn’t been back to the campus since the early ‘70s. When asked why this game, he said, “Why do you think?”

Saturday marked the 50th anniversary of Paterno’s first game as head coach at Penn State, and it was a chance for his supporters to come together and publicly rally for “JoePa.”

“I said it when the statue came down,” one fan told Harris, “we are so strong that nothing can stop us.”

All of this unfolded in front of a makeshift shrine to Paterno, with bricks, photos, signs and balloons. Someone brought a life-sized cardboard cutout of the coach, and several took pictures with it. One woman kissed the cardboard Paterno on the cheek.

“Never forget,” one sign read, “the man that built this house!”

There are the “Never forget” voices for Paterno, and the “never forget” voices for the victims of Sandusky. The two groups can and do overlap, but it was quite clear on Saturday which group was loudest. There was hardly a negative word in the crowd around Harris all morning; the only show of disgust was for a reporter who approached Harris for an interview.

One fan walked up to the scene and said, “So sad.” Her words hung in the air for a moment, and then she continued the thought.

“Sad he’s gone.”

She walked away.

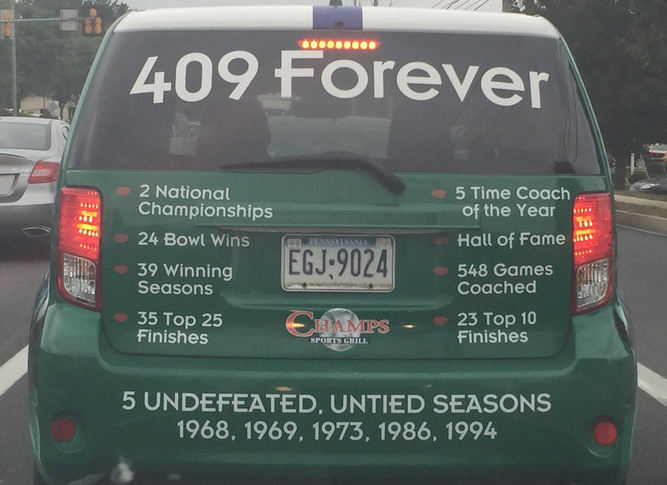

There were other shows of support this weekend. The video board inside Beaver Stadium played three tributes to Paterno during Saturday’s game; each was brief but greeted by loud cheers. The videos focused on the 1966 team, Paterno’s first, and the academic achievements of Paterno’s players, but “409 wins” was mentioned and hagiographic highlights of Paterno’s early days played as well. (Athletics director Sandy Barbour declined an interview request.)

The only sign of disapproval came from the Temple section, where a sign read, “He turned his back, we’ll turn ours.”

The banner was drawn by two Temple fans – one a student named Mike Delaney and the other a recent graduate named Bruce Boyer. They told Yahoo Sports that security tried to take the sign away because it was “disrespectful,” but then relented. The fans did turn their backs during all three Paterno video tributes.

“I know Joe Paterno’s done a lot for this school, for this state, for everything,” said Boyer. “On the contrary, Bill Cosby’s done a lot for Temple. Temple’s not going to honor him.”

For the most part, though, this weekend was full of Paterno praise rather than protest.

On Friday night, BlueWhiteTV, a self-described “Netflix for Penn Staters”, put on an “Honor Joe” event on Beaver Street, featuring former Paterno and NFL player Brandon Noble. Some passersby yelled criticism, but just as many or more cheered them on.

“Our name has definitely been tarnished,” Noble said, “and there’s a black cloud hanging over us, so it’s a way to bring back some of those good memories.” Noble said as a father he understands “both sides,” and “there’s a line we have to walk to be respectful to the victims, but still I want people to know how wonderful this place is.”

There were other famous football alums who couldn’t make it, but were still happy to talk glowingly about Paterno. Adam Taliaferro, who is beloved by fans for his recovery after suffering a spinal cord injury in a game, is now a New Jersey state assemblyman, but he is very much among those defending the coach, the tribute, and the statue.

“Caoch Paterno truly helped me through my lowest point in my life,” he told Yahoo Sports this week. “He did a tremendous amount for the university regardless of what anyone says and he deserves that honor from the university.”

Taliaferro was on the Penn State Board of Trustees when the Freeh Report came out in 2012. The review of the Sandusky scandal, put together by former FBI director Louis Freeh, concluded that the head coach and others “concealed Sandusky’s activities from the Board of Trustees, the university community and the authorities. They exhibited a striking lack of empathy for Sandusky’s victims by failing to inquire as to their safety and well-being, especially by not attempting to determine the identity of the child who Sandusky assaulted in the Lasch Building in 2001.”

It is a damning passage, one that paints a man known for kindness and mentorship as callous and football-first.

Taliaferro is among those who don’t buy the findings.

“Conclusions that were drawn that were never evaluated in a court of law,” he said. “He’s never been charged with a crime. I haven’t put a lot of stock in the Freeh Report. I put stock in what the court says. I’m personally not going to charge [Paterno] with anything he hasn’t been found guilty of.”

Pressed on whether Paterno knew enough to act, Taliaferro responded this way:

“The way I look at it, anyone that you get to know that well, they earn the benefit of the doubt from you. I’m not going to jump in and conclude and assume anything. He did everything he was required to do.”

Harris is even more strident, eager to revisit the case and the evidence. He compares the Penn State situation to the Duke lacrosse saga, where a rush to judgment turned out to be premature.

“If you want to get deep into it, I am here and I will discuss that in-depth at any time,” he told Yahoo Sports. “And if you’re still in the mind frame that Joe Paterno is to blame, the football program is to blame, the players are to blame, you need a re-education, and I’m happy to give that to you.”

He began right away, taking issue with a key anecdote in the Freeh Report, which describes a Sandusky assault witnessed by former assistant Mike McQueary.

“That evening, Mike McQueary never saw anything sexual,” Harris says, and further, “Joe was concerned enough … to say, ‘We’ll pass it on to the powers.’ ”

The debate goes on, in chat rooms and on message boards and within Penn State circles. Emotions have hardly waned here in Happy Valley. Saturday’s Paterno tributes were considered a way to look back – at the 1966 team, at the growth of the program, and at Paterno himself. But it felt a lot more like a beginning. The talk from some players and fans suggests the fight for the statue and the wall and Paterno’s memory is not anywhere near ended, even though many in the community and surely some or all of the victims want this to be a part of the past.

“It’s a start,” Harris said of this weekend’s tribute. “And that’s how I look at it.”