The 'miracle' reincarnation of the Milwaukee Bucks

MILWAUKEE — They dubbed it the Bag Revolt. After assembling on an internet message board, they gathered in person, at the increasingly decrepit home of the Milwaukee Bucks, for a protest.

On March 15, 2008, a few dozen Bucks diehards marched through the halls of the soulless Bradley Center with bags over their heads. They sat peacefully through a lopsided loss to the Boston Celtics, their faces still concealed by brown-paper grocery totes, symbols of both frustration and futility.

You see, long before Anthony Davis wanted to play for them and All-Stars wanted to stay with them, the Bucks were feeble coat-tailers. They lumbered along on the NBA’s treadmill of mediocrity, playing basketball as antiquated as the organization that supported it, surviving on dollars earned by others.

And so, with yet another nondescript night of comprehensive putridity drawing to a close, the demonstrators decided they had had enough. They descended on the lower bowl. Bag Revolt organizer Dan Hoelzl distracted an usher. A dozen of his minions dipped by, down an aisle that would leave them mere feet away from the primary subject of their exasperation: Bucks owner Herb Kohl.

They were soon whisked away after a sarcastic round of applause, Kohl not amused in the slightest. But their message had landed. So had a photo of an unsettled Kohl side-eying a Revolter, who held a sign mocking an NBA slogan that could not have been more out of place in Milwaukee.

“Where Amazing Happens,” it read, the irony devastating.

Not much amazing happened in Milwaukee over the three decades of the Bradley Center’s existence. Thirteen coaches came and went. Two hundred and sixty-one players did, too. Combined, they won three playoff series, the last in 2001.

And yet in 2019, the drought will almost certainly end.

In 2019, the Bucks sit atop the NBA. The former bane of big-market existence for revenue-sharing reasons has become big brother. The cellar-dwellers five seasons earlier are now selling out games; outselling traditional powers in merchandise shops; and selling superstars on success.

In 2019, Davis said he wanted out of New Orleans, and the NBA intelligentsia told small-market squads that they no longer stood a chance. Then a funny thing happened. Davis reportedly handed the Pelicans a list of four desirable destinations: the Los Angeles Lakers, New York Knicks, Los Angeles Clippers … and Milwaukee Bucks.

Yep. Milwaukee.

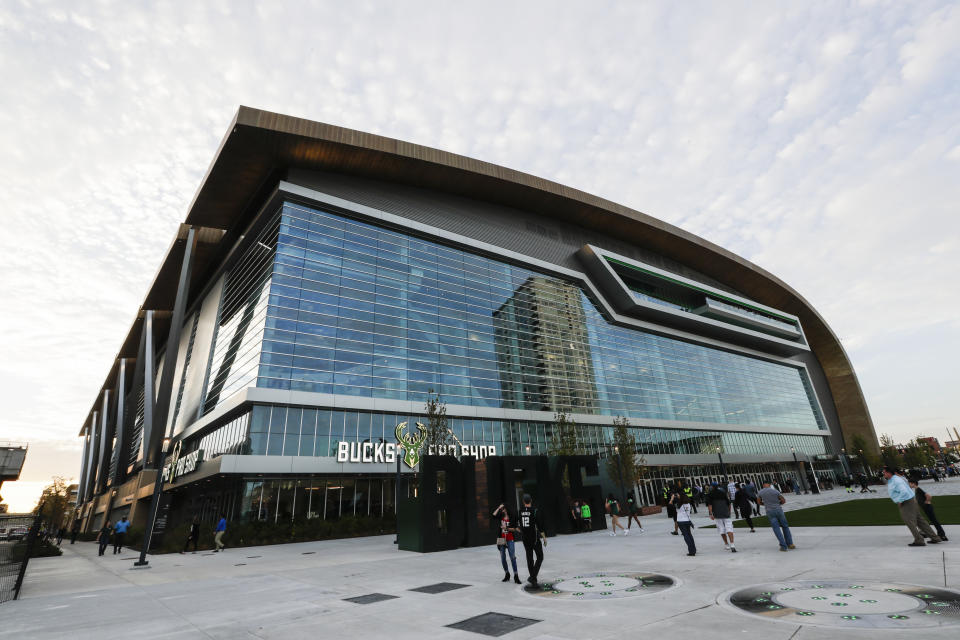

Because these are basketball boom times in MKE, suddenly the summit of a league that for years all but ignored it. The Bucks, a once-proud but more recently moribund franchise, are on pace for 61 wins, their most since 1971-72. Wisconsinites, New Yorkers and Europeans all want to watch them. Davis wouldn’t mind playing for them. Behind the scenes, in less than five years, the organization has more than tripled in size. Its value has more than doubled. And Fiserv Forum, the avant-garde $524 million palace that hosts all the vibrancy, is by many estimations the nicest venue in the NBA.

All of which explains why, even with a biting wind exacerbating sub-freezing temperatures outside, the metaphor of choice in and around the Bucks organization is the “perfect storm.”

But there’s a caveat. An important one. The concept of a “perfect storm” implies luck; perhaps even impermanence.

This, Bucks co-owner Wes Edens says, “is the residue of good planning.”

And of good fortune as well. But the literal worst-to-first ascent of the Milwaukee Bucks is not an accident; it is by design. And 2019 is not necessarily a culmination; it may, on the contrary, be a beginning.

The treadmill of mediocrity

Herb Kohl loves the Bucks. He garnered affection as a homegrown owner and philanthropist, and reciprocated every ounce of it. The former U.S. senator never married. Instead, after buying the team in 1985, he flew to Denver ahead of a matchup with the Nuggets to tell players and coaches he’d treat them like family. And he meant it. He cared deeply, listening in to radio broadcasts via phone calls while representing Wisconsin in Washington, and hanging out of his 27th-floor apartment window after losses. Heck, he saved the Bucks at least twice. He is a Milwaukee hero.

But he ran a 1990s NBA organization in a rapidly evolving 21st-century league. At the end of his reign in 2014, he employed only 90 non-players full-time. The team’s offices, as one employee puts it, were “crummy.” Its practice facility was a 15-minute drive south, inside the suburban Archbishop Cousins Catholic Center, where it shared a swimming pool with nuns.

As it floundered in the 2000s, attendance dipped – below 90 percent of capacity, then below 80; into the NBA’s bottom 11 each of the final 14 years at the Bradley Center, and more recently into the bottom five. Old Ray Allen jerseys got buried in closets and were never replaced. Fans disengaged.

By 2014, the Bucks ranked last or near last in every single one of the NBA’s quantitative and qualitative business metrics. They were its worst basketball team and its least valuable franchise. They were, according to Kohl, losing money annually.

After Kohl announced his intention to sell, in effect acknowledging that the league had passed him by, several billionaires explored a purchase. One of them was a then-54-year-old hedge-fund chief named Marc Lasry. Asked now if there was one aspect of the franchise that seemed particularly below standard at the time, Lasry hesitates. “Um,” he begins, searching for an answer, “I think everything.”

But as other owners and NBA executives told Lasry and Edens as they considered the acquisition, there was a positive spin. As Lasry says, quite simply: “Could only go up.”

The elements of a perfect storm

Today, the Froedtert Sports Science Center, the Bucks’ ultramodern practice facility, stands as one of many emblems of the franchise’s growth. It houses everything from a sophisticated weight room to a barber shop; two full-size practice courts to hydrotherapy pools; a draft-night war room to a kitchen. And on this frigid January morning, a gameday shootaround.

At around 10:45, doors to the gym swing open as the Bucks finalize preparations for the Miami Heat. The excessively evil-looking deer logo that has come to symbolize a new era looms on side walls. Flags representing players’ heritages hang from the ceiling. Giannis Antetokounmpo strides off the court underneath the national colors of Nigeria and Greece.

As he does, Bucks broadcasting legend Jim Paschke surveys the scene, soaking up the positive vibes, unmistakable offshoots of the perfect storm. And when presented with the metaphor du jour, he extends it.

“Perfect storms,” Paschke points out, “form from a lot of different elements.”

The essential element was the arena. Because without it, Seattle or Vegas beckoned. Adam Silver sounded the first alarm in 2013, labeling a 25-year-old Bradley Center inadequate. When Edens, Lasry, Jamie Dinan and Mike Fascitelli bought the team from Kohl for $550 million in 2014, the former senator sacrificed additional millions for the stipulation that it would remain in Milwaukee. But the purchase agreement reportedly included a clause that allowed the NBA to buy the team and pursue relocation if arena plans did not crystallize in due course.

Kohl, upon selling, put $100 million toward the then-$500 million project. The new owners eventually offered up $150 million, but refused to budge much further. So team president Peter Feigin lobbied relentlessly for taxpayer support. At one point, when funding for the arena was stripped out of Wisconsin’s budget, the personable yet exacting New Yorker made one-on-one appointments with all 99 state representatives in Madison. Under Feigin’s pressure, and by extension the NBA’s, the legislature caved, and controversially approved $250 million in public funding. In doing so, it kept the Bucks in Milwaukee, reaffirmed Kohl’s legacy as a savior, and enabled the franchise’s rebirth.

But there’s no denying the storm’s most dynamic element is Antetokounmpo, who at the time of the regime change was an anonymous, uber-raw teenager coming off a 6.8-point-per-game rookie year. Five seasons later, he is arguably the single most valuable asset in the NBA and an invaluable actor in Milwaukee’s revitalization. The arena kept the Bucks here; Giannis’ otherworldly talent has made them relevant, his development altering the course of the franchise for good.

Despite the unicorn’s All-Star ascent, though, on-court progress stalled. Last January, with the team just a game above .500, head coach Jason Kidd was fired. In May, 35-year-old GM Jon Horst teamed with Feigin and the owners to lure Mike Budenholzer to Milwaukee as Kidd’s replacement. And almost immediately, a culture shifted.

Behind Bud’s “let it fly” mantra, confidence skyrocketed. With the floor spread by six 37 percent-or-better 3-point shooters, Antetokounmpo has soared to MVP levels. The results are 50-point quarters and long-range barrages; the league’s best record, 41-14; its best net rating; and its best point differential, a whopping two per game better than Golden State’s.

For just the second time in 30 years, the Bucks will eclipse the 50-win mark. They’ll finish with an above-average offense and above-average defense for the first time since 1990-91. Five seasons after failing to win two games in a row, they haven’t suffered back-to-back losses. Back inside the sports science center, guard Malcolm Brogdon says the team “absolutely” takes pride in that stat.

But duck out of shootaround, across a perplexing intersection, halfway around Fiserv Forum, and a physical juxtaposition contextualizes the revival as well as anything can. To the north, Fiserv glistens. Meanwhile, to the south, cranes rumble, chipping away at the Bradley Center’s exterior. On the street-facing east side, shattered glass sits still beneath blown-out windows. “DANGER” notices hang from a ragged chain-link fence. An upended “ROAD WORK AHEAD” sign rests inside it.

Forty-eight hours after the old arena’s roof is imploded, heaps of rubble remain as evocative reminders of darker days.

Recapturing Milwaukee

Feigin still remembers the “sea of red.” Not the date – Nov. 5, 2014 – nor the score – a 95-86 loss. But he remembers his second home game as Milwaukee Bucks president for the stunning sight that accompanied it: Bulls fans. Thousands of them, packing the Bradley Center’s lower bowl, outnumbering hometown supporters on a Wednesday night.

Upon seeing the breakdown, Feigin pulled a figurative “fire alarm.” He summoned a group of a half-dozen executives to the box office in shock. He spoke with customary intensity, demanding change. The “sea of red,” initially, had been jarring. “And the reaction,” he says, “was correction.”

The Bucks, Feigin says, were “the most distressed asset.” On multiple occasions, he compares the project he took on in 2014 to a “startup.”

“We had lost this generation of fans,” he explains, referring to one consequence of a decade of irrelevance. And winning them back was a massive task.

One of the people it fell to was Dustin Godsey, who learned of the size of the task in ominous fashion. Godsey was the franchise’s first-ever marketing hire in 2012. In Milwaukee to interview for the job that April, with the Bucks in a tight playoff race, he sidled up to a hotel bar and asked for that evening’s game against the Detroit Pistons to be put on a TV. “They wouldn’t even turn the game on,” he recalls now. “That was where we were at in the community’s mindset at that time.”

After the regime change, Godsey and Feigin spearheaded the offensive. “We had to go out and be where people were,” Godsey, now chief marketing officer, says. That meant community festivals, schools and group events. It meant fan fests and summer bashes. “We went hog wild,” Feigin says. “Across every demo, in every neighborhood, in 65 of [Wisconsin’s 72] counties.” He spoke at basketball clinics and to corporate clubs, selling hopes and dreams that nowadays are coming to fruition.

He also set out to professionalize an organization that had fallen behind. In four-plus years, Milwaukee’s non-playing staff has grown from 90 people to 315. It has moved out of those “crummy” offices and into a new sixth-floor hub; out of that suburban practice facility and into the new, state-of-the-art one. It now boasts a director of basketball strategy, a director of basketball research, and a manager of basketball analytics; a sports science data analyst, three team chefs and a 56-person ticket-sales department.

When the on-court product exploded, the revamped marketing efforts gave Milwaukeeans “touchpoints” to latch onto. And the business-side expansion allowed the Bucks to capitalize. They sold over 10,000 season tickets in 2018-19, five years after sitting in the NBA’s basement below 2,500. They now offer standing-room-only tickets, and expect their sellout streak, currently at 12, to continue through season’s end. Over the final three months of 2018, they leaped into the league’s top five in merchandise sales, propelled by Giannis’ fourth-ranked jersey.

Which leads to a key point, one made by basketball and business folks alike: None of this would be possible without the Greek Freak. Deficient products don’t sell. Antetokounmpo and Budenholzer are exponentially more important than any account service executive. Arena-adjacent real-estate development will line owners’ pockets with non-basketball-related income, but will never eclipse hoops as the company’s core business.

The infrastructure, however, matters. After basketball and a building, it’s the third vital element of the perfect storm. Because it’s the reason these boom times are sustainable.

A small-market destination?

Shortly after the ownership change in 2014, Edens and Lasry held several meetings with the Bucks employees they’d be inheriting. During one of these meetings, Edens scanned fresh faces and issued a decree.

“Anybody in this room that doesn’t think that it’s a reasonable goal for us to win an NBA championship because we’re a small market should just leave now,” the Bucks’ co-owner said. “If you really believe it, and you don’t leave, I’ll find you and we’ll ask you to leave. Because that’s the goal. Period.”

It’s a message he reiterates five years later, and one that contradicts much of what the modern NBA has taught us. A day before our conversation, Davis had publicized his desire to leave New Orleans 18 months before hitting free agency. Many interpreted his trade demand as yet another death knell for “small-markets.”

And although some Bucks executives chafe at the term, it undoubtedly applies relatively to their city. Milwaukee ranks 27th among NBA media markets. Throughout five-month winters, it is gray and cold. To Joel Embiid, it’s a “s—hole.” On a Tuesday afternoon in January, it is a ghost town, its jaywalkable streets a far cry from the bustle of Manhattan or glamor of Los Angeles.

But start talking about small-market challenges in the presence of Lasry, and his voice gains an edge.

“I don’t think it’s a challenge for small-market teams,” he begins. “I actually disagree with that.”

“I think what every player wants is to win,” the Moroccan-born New Yorker continues. “That’s really it. If Anthony Davis [and] the Pelicans were reaching the Finals, the Western Conference finals, they were challenging and they were playing really well, I think he’d be very happy. I think what frustrates him, and what frustrates players, is knowing you’re one of the best players in the league and not winning. If you’re in a large market, if you’re playing for the Lakers, and you’re losing, you don’t turn around and think, ‘Oh, thank God I’m playing for the Lakers,’ or ‘I’m playing for the Knicks.’ You’re going to feel the same way. Which is, ‘I want an opportunity to win.’”

Sure enough, in the days after Lasry uttered those words to Yahoo Sports, Davis unknowingly reinforced them.

This, the Milwaukee Bucks, is a franchise that boasts Matthew Dellavedova, who was traded in December, as one of its most expensive free-agent acquisitions. Yet this is a new age, under new leadership, with the resources and desire to contend. Not only are outsiders intrigued; current stars hint at long stays.

“Giannis has been here his whole career, and he hasn’t told us or made us think that he wanted to leave,” Bucks forward Khris Middleton told reporters after a recent win. “From everything I’ve heard, he wants to be here for the rest of his career, and I feel the same way. For us, it’s not being in the right market, it’s being with the right team. This organization, they’ve done everything that they can to make sure we succeed.”

“At the end of the day,” Lasry says, again several days before news of Davis’ list, “all these guys care about is winning, or having an opportunity to win. Anthony Davis played there seven years. And he’s been to the playoffs twice. That would frustrate me.”

Can the Bucks keep their core together?

A couple hours after a 124-86 bludgeoning of the Heat, Hoelzl, the Bag Revolt-organizing diehard, is sipping Schlitz beer out of a koozied can at Buck Bradley’s, the longest bar east of the Mississippi River. As Springsteen floods the arena-neighboring establishment, Hoelzl savors the team’s success. Heck, as a lunatic who’s watched every single Bucks game in its entirety since 2001, he should be reveling in it. Years of Deer fandom, however, have conditioned him to remain skeptical.

Astute Bucks supporters are proceeding with caution despite the team’s table-topping status, in large part because four of its five starters are set to hit free agency this summer. Middleton will almost surely decline a $13 million player option. Brogdon (restricted), Eric Bledsoe and Brook Lopez (both unrestricted) will also hit the open market.

Collectively, they are expected to earn somewhere in the vicinity of $75 million per year – a $42 million combined raise. To bring back all four, Milwaukee might have to cross the projected $132 million luxury tax threshold for the second time in team history.

So would the owners be willing to?

“I can only say personally, we’re in it as a partnership,” Edens says. “But my answer is absolutely.”

Says Lasry: “We’ll figure it out. I think right now, it’s a bit early. We’re gonna see how everything goes. It’s gonna be a function of how well we do in the playoffs. … Let’s say we win the NBA championship. Would you argue that we should keep the team together? Yes. Let’s say we get knocked out in the first round. Then we have some questions.

“… Right now, we’re either the best team in the league or the second-best team in the league. That’s great – that’s the regular season. So, let’s see how well we play in the playoffs. Then I think it’s easier for us to make some of those determinations.”

Basking in the glow of a ‘miracle story’

Inside Fiserv Forum, however, nobody is worrying about cap holds or George Hill buyouts or the repeater tax. Climb the stairs up to the Panorama Club, an open, nightclub-like lounge in the rafters, and you can see for yourself. Perhaps step out for a breath of fresh air, onto the top-story balcony, where awestruck visitors pose for pictures with downtown Milwaukee as their backdrop. Or seek out a perch along the club’s court-facing railing for a bird’s eye view of the game. With fourth-quarter seconds ticking away and another W in hand, a group of young women give up their spot at the railing and head for the exits. As they do, one says in a sing-songy whine: “I don’t want this game to be oveeerrrrr.”

Throughout the arena, thousands cling to the moment, unwilling to let it slip. Ushers and condiment-stand cleaners hate missing games. Veteran followers and first-timers arrive 90 minutes before tip. For years, Godsey and the Bucks blasted them with the marketing slogan, “Own The Future.” Now that the future has arrived, long-suffering fans bask in its glow.

Peering out over a suite-level railing, John Steinmiller’s bespectacled gaze falls upon them. Milwaukee’s executive VP of operations joined the franchise’s then-10-man front office in 1970. In his 48 years with the club, Steinmiller has distributed tickets, marshaled summer camps, written media guides, even arranged letters on the marquee outside the MECCA, the team’s first home. He eventually rose into a business executive role that he held for over three decades.

In other words, Steinmiller has seen it all over the years – except for this, the stream of humanity filling the main concourse and atrium an hour before tip, which prompts the question: Has there ever been this much excitement around the Milwaukee Bucks?

“Oh, no,” Steinmiller says, his five decades of past experiences eclipsed by the present.

Forty minutes later, Feigin wanders amid the buzz, pointing out one or two of the 79 pieces of public art that infuse the amenity-laden arena with personality. He interrupts the tour to greet various acquaintances, some with a bro hug rather than a formal handshake. Some call him “brother” or “bossman.” One stranger stops him and whips out his phone to pull up a photo. It’s of him and Feigin, in construction vests and hard hats. The man literally built the place.

As Feigin weaves in and out of patrons, he marvels at the entire experience. “Oh, this is the best,” he says with a certain childlike enthusiasm.

There is little time nowadays to reflect on half-empty Bradley Centers or Bulls-red invasions, and on how far the franchise has come. Little time to reminisce about hundreds of job interviews and fiery meetings. Little time to ponder all the “what ifs.” What if the Wisconsin legislature hadn’t reversed course? What if Giannis Antetokounmpo didn’t exist? What if any of the perfect storm’s elements had fizzled out at sea?

But it did, he does, and they didn’t. Instead, they inspired a reincarnation that transcends the word “remarkable.” Racing through the bowels of the arena, the longest-tenured Bucks employee finally stumbles upon an apt description.

“It’s the story of a miracle,” Steinmiller says. “It really is.”

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Costas confirms reason he got pulled from Super Bowl

• Former NFL first-rounder’s mixed debut with AAF

• New football league wins the night, tops NBA in ratings

• Bushnell: The ‘miracle’ reincarnation of the Bucks