Michael Oliver issues 11 red cards as he re-referees Chelsea vs Leeds 1970 FA Cup final replay

This article was first published in April 2020

We are not even 14 minutes into the FA Cup final and Michael Oliver, the English game’s leading referee, has already decided on the first sending off – although the player in question will later go on to score the winning goal in one of the greatest finals in FA Cup history.

“You would be definitely going second yellow on that one,” Oliver says, on the other end of the WhatsApp call from his home in Ashington in Northumberland. For a moment he seems momentarily lost for words. We have spent some of the opening stages of the game discussing what it is like to referee an FA Cup final, as Oliver did. The frenetic pace, how much a referee can reasonably let go, when to put down a marker. But no referee wants to give a red card this early in a final.

Oliver says he might expect a video assistant referee to recommend an upgrade to a straight red. “I might have to change that,” he mutters with the self-reproaching tone of the perfectionist. But either way, David Webb is off. First booking for cleaning out Eddie Gray in the first two minutes. The second for going straight through Allan Clarke. Over the following 90 minutes and extra time, Oliver will decide Webb deserves a third booking. This is the 1970 FA Cup final replay, remembered in part for a heroic performance from Chelsea’s converted centre-back who headed in an extra-time winner.

Oliver was the Premier League’s youngest-ever referee aged 25 and had been in the heart of what was to become the European coronavirus outbreak in Milan for Atalanta’s Champions League first leg win over Valencia. Since the outbreak, at 7am every day he could be found in the gym putting in the work ready for football’s resumption. How about, I wondered, re-refereeing the entire 120-minute 1970 game between Leeds United and Chelsea, notorious for its full-blooded, old-school, kick-and-be-kicked intensity?

The 1970 replay has been re-refereed before. In 1997, David Elleray, then considered the English game’s most senior referee, awarded six red cards and 20 yellows to the 23 players who appeared that day at Old Trafford (for some reason, Don Revie never saw fit to call upon his one substitute, Mick Bates). Elleray’s card-count was an increase on the numbers recorded by the referee on the day, Eric Jennings of Stourbridge, then 47 and resplendent in white collars the size of which would be considered large even in the 1970s. Jennings booked one player, Chelsea’s Ian Hutchinson, who died aged 54 in 2002, and was one of his side’s outstanding performers that day.

At the end of two gruelling hours on YouTube, Oliver, a man who has refereed the big six in the Premier League many times and himself awarded a penalty to Chelsea in the 2018 FA Cup final, looks at his notebook in wonder. A lot has changed in 50 years. Oliver has dished out 11 red cards, two of which were for Chelsea’s Eddie McCreadie. Of the 16 bookings there are three apiece for Webb, Hutchinson and Charlie Cooke. Seven of the reds are for Chelsea players as well as Norman Hunter, Eddie Gray, Jack Charlton, and Billy Bremner.

“It’s amazing to watch them – not a single player ever appeals to the referee,” says Oliver as Webb, technically sent off by now, thunders into another challenge. “Eddie Gray just gets up. You didn’t get the reaction then that you do now. And what you also don’t get is 20 more players running into the situation in the aftermath. Which [nowadays] means you invariably end up with more hassle and more cards anyway.”

He looks on in amusement at first and then later, as he gets used to the rhythm of the game, he senses something else. “For want of a better explanation,” he says after a while, “it’s almost ‘proper football’. They kick each other and get on with it and never complain”. As for the implacable Jennings, refereeing his last game before going back to his day job at a water treatment company, I venture the observation that he does not seem to be moving very much.

“By saying ‘not moving very much’, do you mean not moving at all?” asks Oliver – and it is hard to argue. The modern referee has to pass his pre-season fitness test every summer but Jennings, who died in 1988, could be said to be keeping an eye on the game rather than officiating it. He barely leaves the centre circle. When at last he does take Hutchinson’s name it seems more to give himself something to do. Even as Chelsea fall under intense pressure around 20 minutes in and the tackling becomes more reckless, the genial Jennings largely stays out of it.

“Each tackle gets a little bit worse there,” Oliver says of one fraught passage of play. “[In the modern day], you’d be looking for a reason to calm everyone down. All you get there are five or six tackles in 15 seconds that get progressively worse.” Suddenly the next two red cards in the game come, from an exchange of blows between McCreadie and Hunter. “They throw a couple of punches and get on with it,” Oliver says. “Now everyone would be in. A lot of the time those players coming in are genuinely trying to separate people but it’s hard to convey that. If a player sees someone run in from the other side, then he runs in.”

We are now playing 10 v 9 and the first half has only just passed its midpoint. Only once did Oliver show three red cards in a game: Leeds v MK Dons, April 2010, with two of them late on. He decides that Mick Jones, the Leeds centre-forward, should be booked for a charge on Peter Bonetti. After prolonged treatment, the Chelsea goalkeeper, who died aged 78 this month, is never the same for the rest of the match. “If he needs treatment then he is genuinely hurt,” observes Oliver.

Oliver was what you might call a referee prodigy, the son of a Football League referee, Clive. Michael took charge of his first game aged 14 in 1999 in the Under-11s Coast Colts League in Northumberland. Within eight years he had refereed his first Football League game. He would have refereed his first Premier League game aged 24 but Fulham v Portsmouth in January 2010 was postponed and a week later a scan revealed he had been trying to run off a broken leg.

He spots a bad tackle by Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris on Gray that is not immediately recognisable as such on the old BBC footage. “This is the infamous one where he can never win the ball,” Oliver says, and deconstructs it swiftly. The ball is on the floor and Gray has nicked it around Harris. The challenge is with a straight leg and Gray is holding the back of his knee in the aftermath. Oliver is piecing together the evidence that confirms what he saw in the moment. “The fact that Ron Harris is apologising shows that he knows what has happened.” It is a red card for Chopper.

By half-time Gray is off too, for a retaliatory stamp on Hutchinson. As he blows his whistle for the break we wonder whether Jennings retires to the referee’s room for a traditional cup of tea. Oliver and his two regular assistants, Stuart Burt and Simon Bennett, have an energy drink at the break. They take it in turns to bring in sweets – Squashies, Jelly Babies. Their hope is always that the game goes smoothly and their contribution is unremarked upon, although that does not mean intervening as little as possible.

Oliver’s highest-profile decision was dismissing Gianluigi Buffon in a 2018 Champions League quarter-final after awarding a penalty against Real Madrid that gave them a late victory. Buffon lost the plot in the aftermath – “the referee has a rubbish bin for a heart,” was among his early post-match outbursts. The goalkeeper later apologised. Oliver received death threats in the interim.

Oliver was right on both counts that night – penalty and red card – and yet he was attacked by a famous footballer which had the effect of rallying the worst kind of online abuse. Referees are not permitted social media accounts and in the circumstances that is probably wise. No-one stands up for them. Why, the eternal question goes, would you want to be one?

Oliver was a good schoolboy footballer, and attended the Newcastle United academy for a while, “a centre-half who didn’t tackle or head – a mystery why I didn’t make it!” He was captain of his school team, played for a local club, for the county and then at Newcastle alongside Michael Carrick’s brother Graeme. Playing and training every night, he fell ill and made a decision to have a year out. “My dad suggested I do the referee course as a way of picking up some extra pocket money,” he says. After two years of junior football he began refereeing the adult game and progressed with remarkable speed.

Into the second half and Peter Osgood takes action to evade a bad Charlton tackle that is intended to hurt. The Leeds defender, another Ashington boy, is off – the sixth red card before the hour. The game is starting to feel wild. Osgood and Bremner are both, Oliver decides, on final warnings. Webb is on his third booking. Hutchinson gets his second yellow, the seventh dismissal. Then Bremner and Charlie Cooke go off for their second yellows. Chelsea are down to six players and, technically speaking, it would be match abandoned. It is Cooke’s assist for Osgood’s equaliser on 78 minutes.

As Leeds press for a winner before the end of the 90 minutes, Oliver spots a second red for McCreadie, the tenth of the match, for a high boot on Bremner and what should be a penalty for Leeds. “He’s effectively kicked him in the head.” Extra time looms. “At this point, in a game like this, as a referee,” Oliver admits, “you’re just praying for someone to score.”

Osgood is the eleventh and last red card in extra time, a second booking for a foul on Leeds goalkeeper David Harvey. He was, after all, on a final warning. We discuss the infamous career-changing foul by Emlyn Hughes on Osgood in 1966 that broke the latter’s leg – after which he was never the same. “You don’t get people who go out to do others now,” Oliver says, “you don’t get the tackles now where people try to hurt each other.”

Webb’s scrappy header makes it 2-1. Sensing victory the Chelsea support do something that would now invite immediate expulsion from Stamford Bridge. They sing “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. Oliver recalls his first Premier League game in August 2010 when he blew the final whistle at St Andrews just as Morten Gamst Pedersen struck a shot that would have been the equaliser for Blackburn Rovers. “Had it gone in that would probably have been the start and end of my career,” he reflects. “It just went into the side netting.”

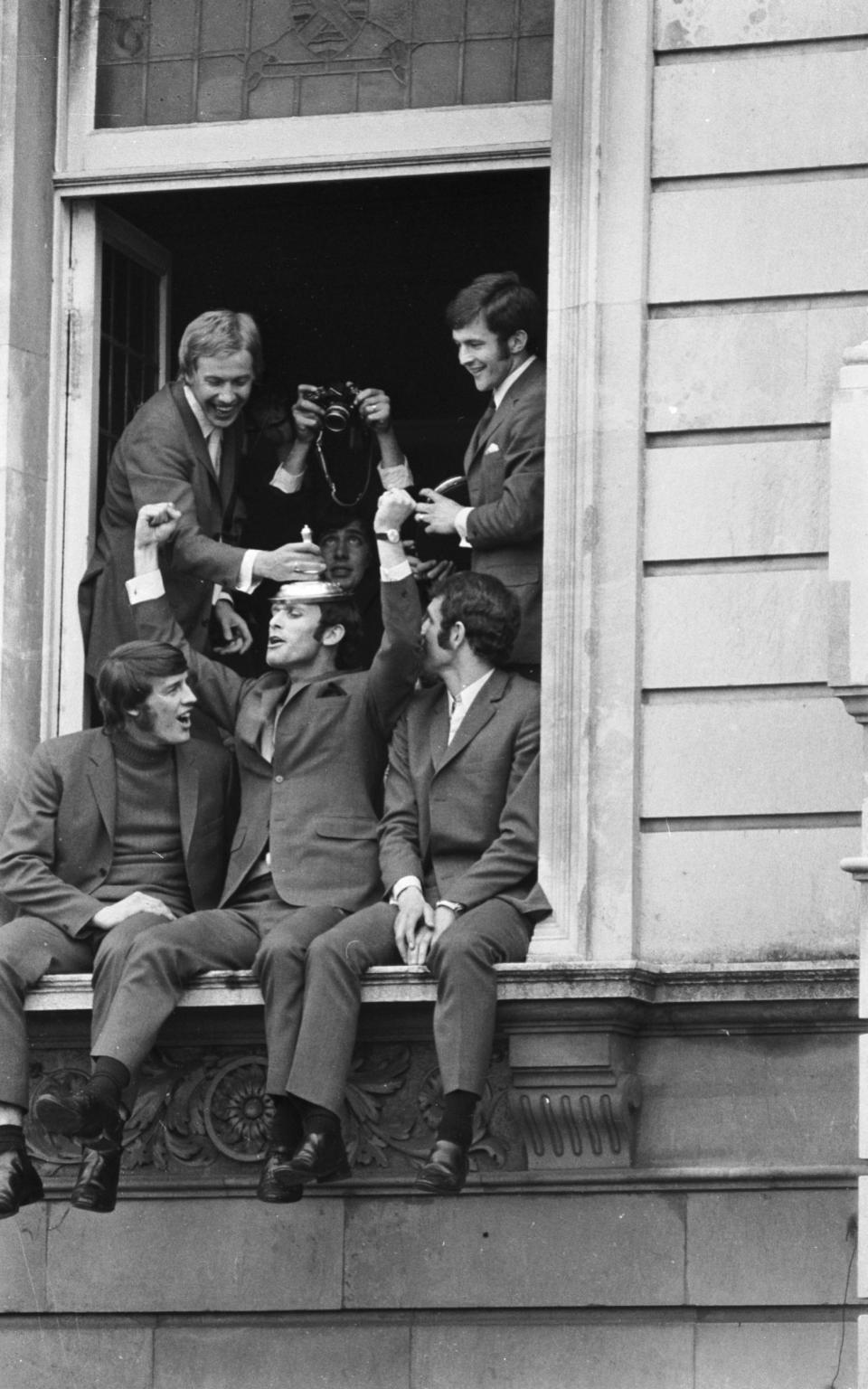

His last booking of the 16 is for the Chelsea substitute Marvin Hinton. By the end though, something strange has happened to Jennings – he seems to be running more. “Second wind?” wonders Oliver. The final whistle goes and Oliver has spotted 11 red cards, five more than Elleray dismissed in the same exercise more than 20 years ago. “It’s moved on again, hasn’t it?” says Oliver. The players are exhausted but there is no aggression or feuding after the whistle, just handshakes and commiserations to the losers. Mr Jennings is off to get his medal, reflecting, one assumes, on a good evening’s work.