“What if We Just Made a Horrible Mistake?” On Adding Kids into a Pro Climbing Career

This article originally appeared on Climbing

In 2015, Majka Burhardt was living the life she'd always wanted. She was a professional climber and alpine guide, careening between her beloved ice climbs in New Hampshire and dream crags around the world. The problem? Burhardt--who was 39 and happily married to a fellow die-hard climber--also wanted children.

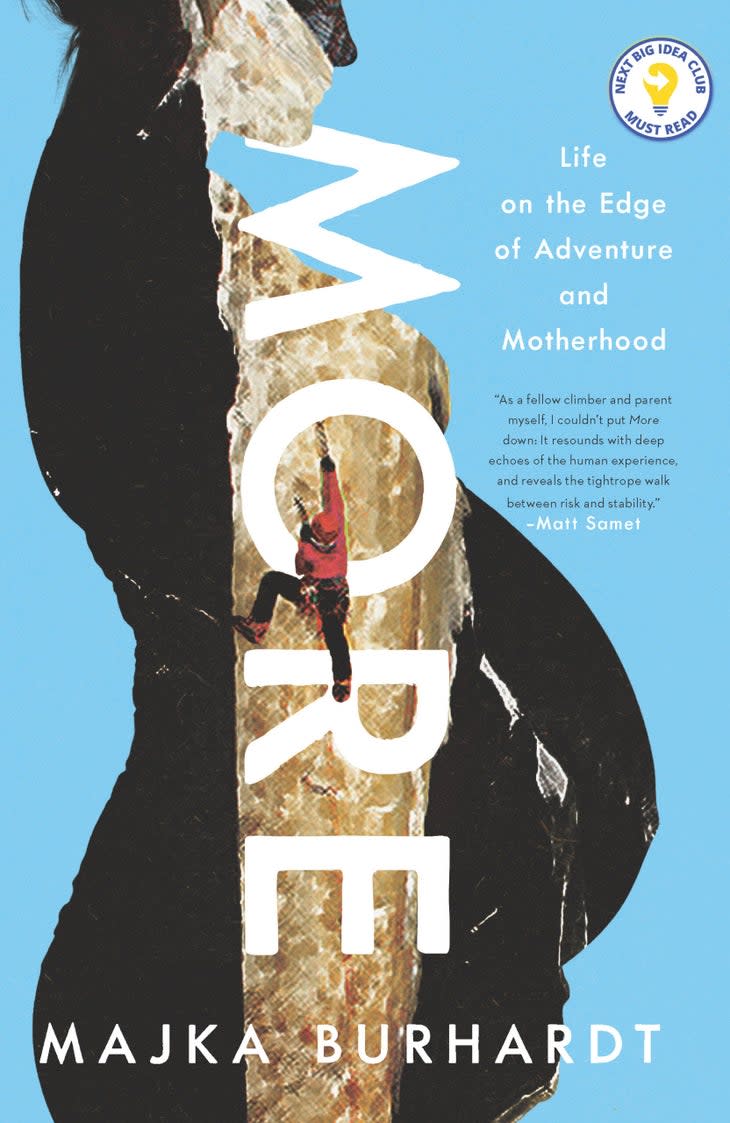

That tension--between climbing and family, freedom and obligations--is at the core of Burhardt's new memoir, More: Life on the Edge of Adventure and Motherhood, a flowing collage of a book built out of five years worth of audio notes, diary entries, and letters. And it's a tension that was only made more frightening when, in 2016, Burhardt gave birth to twins.

As Corey Buhay noted in her glowing review:

"The book describes Burhardt's painful metamorphosis from nomadic adventurer to pregnant spouse, and from full-time athlete to work-from-home mom. But through even the darkest moments, Burhardt has a talent for finding the bright spots. Some scenes are pure comedy. Others are punchy and self-deprecating, more Bridget Jones Diary than high drama. Together, they paint a story of a woman you feel like you know. A woman who, in many ways, reflects the conflicts so many of us face as we transition in and out of climbing and in and out of wanting something more.

More is a window into the life of someone who is being turned upside-down and inside-out before our very eyes. It's the story of a woman who's struggling to make sense of her new self and at the same time raising children in the era of Donald Trump, the Covid-19 pandemic, and George Floyd. All the while she's fighting to reshape a marriage that was founded on climbing, unearth long-buried traumas, and build a non-profit organization… that works to build a more holistic, equitable approach to conservation in sensitive environments across the world."

--Steve Potter, Digital Editor

November 18, 2015

Video Journal | Six Weeks and Five Days Pregnant

I am attached to the world by four metal teeth, each penetrating a frozen smear of water no more deeply than a grain of rice.

Actually, we are attached.

I have one ice tool in each hand and a crampon on each foot. I'm anchored to the world by filed tips of steel the same size as you, all of us together on the barely frozen November ice.

I've never thought about the relative attachment strength of a grain of rice to ice until I learned that this was your size at six weeks in my belly. I'll make you a deal: you stay in my belly and grow bigger, and I will handle the climbing. So far, two hundred feet up a six-hundred-foot scar of ice and rock, swinging weapons disguised as climbing tools at a frozen gash still seems reasonable. This is my sport. When I'm ice climbing, I feel whole.

Today, your dad and I are climbing and I'm testing how it feels to swing tools at ice with a stowaway. Your dad has had nothing change in his body in the past six weeks.

Do you want to know a secret? This isn't your first ice climb. A month ago I carried you up this same climb--the Black Dike on Cannon Cliff--without knowing it. On that day it felt great to be out in front, levitating on frozen water tendrils.

Today, my pants are tighter and I'm letting your dad go first. It sucks. For me, at least. It's likely your dad's dream has come true. We've spent eight years tabulating whose turn it is to be in the lead while climbing, all the while pretending we're not keeping score. I wonder if he will be up for making a deal that, in the future, I can get back on demand anything I've given up during pregnancy?

Likely not, I think.

You should know that for most of my life I have pushed myself to do whatever is bigger and harder, as if achieving at the edge of difficulty makes the feat more worthy.

I already feel myself slowing down to accommodate you and can't tell if I should be proud of myself or terrified.

December 1, 2015

From the Notepad | Eight Weeks and Four Days Pregnant

You are two.

December 4, 2015

Audio Journal | Nine Weeks Pregnant

It's 10:59 in the morning, it's forty degrees out and sunny, and I'm driving to Portland, Maine, to see my physical therapist and trainer to talk about growing you and staying strong at the same time. Don't worry--I have my two hands on the wheel. Just like there are two of you. You each are growing hands, hopefully two apiece, in my belly. I'd like to tell you I am writing you a letter, but it's good to fess up now that I've always been a talker.

A man crosses the street in front of me with a one-year-old on his shoulder. A dad and his kid, no doubt.

Before, I might have thought the scene sweet at best, delaying my drive at worst. But today? Envy. Total body-shaking envy. Because all I can think is that I won't be able to do that with my children--you-- because there will be two of you. What will I do instead? Walk across the street with one of you on my back and one on my front? One on my shoulders and one in my arms?

I want you to know I had a plan for this. And I want you to always be wary of what comes next whenever anyone tells you they have a plan.

I had a plan that your dad and I would try to have kids. That was all I knew I could commit to, and all I asked your dad to commit to as well. If the try worked, the plan would land on us having one kid--and no more--so I could finally wrap my head around motherhood. That we could seamlessy give up our comfortable, childless lives solely based on the fact that we'd only be parenting one child--a kid who would be easy. A traveler. An independent kid. A kid we'd take everywhere. We could handle it, I told myself.

In my plan, Peter and I could both still be driven. I could have my career and I could be a professional athlete, and, and, and . . .

My life has largely been about and, and, and. I grew up seeing that you could do everything because that's what my parents did. Granted, they might have been able to do everything because they were divorced and each had the means to hire a full-time nanny who transferred between parental homes with my sister and me in an alternating two-day and five-day shared split set on an endless loop for my childhood.

For right now, I want you to know: I want everything. I want to be a professional climber, I want to direct a revolutionary international conservation organization, I want to be able to write, I want to be a good partner, and I want to be a mom. Your mom. A mom of twins.

*

You should know I'm not driving anymore. I can't drive when I cry this hard. Instead I am on the side of the road with the car akimbo, straddling pavement and frozen dirt.

Twins. My body is shaking from sobbing.

Buying tickets to Kenya! reads a text message on my phone. It's my climbing partner Kate. I cry harder.

So fun! I write back while snot drips on the phone.

Next time you' ll have to come, she writes back.

I'm laughing and crying now. How is anything I have ever planned going to be possible with two of you? How can I plan now when I have never known so little about anything in my life?

I also cried and laughed when I found out you were not just one, but two.

"Here we go," I said to your dad when I heard the news.

"Here we go," I say to the empty car interior, speaking to all of us now--you two as cherry-sized orbs, and your dad and me together.

December 4, 2015 (Later)

Audio Journal | Nine Weeks Pregnant

I'm still driving to Portland.

We're going two hundred percent. That's my new plan. I discovered two hundred percent last year in Mozambique on our second expedition to launch Legado--that big, revolutionary international conservation organization I mentioned I am still working to make happen. It was two a.m. in the small town of Gurue, Mozambique, and I had to get a team of eighteen people speaking five languages, seven hundred feet of climbing rope, two hundred pieces of climbing protection, two gallons of ethyl-alcohol preserve, three microscopes, ten tents, sixty-two cans of tuna, and one snake hook to the base of a 2,000-foot granite wall twenty-two miles distant that caps off the 7,940-foot Mount Namuli--where we'd live for the next month. "We give it two hundred percent," I told everyone. And I kept asking for that and giving it for a month.

That's the world I have been in since, accelerating Legado at every possible moment. You wouldn't think it would have led me to you. But then again, you don't know about my toe rot.

*

Five months ago, I landed in France to climb after three back-to-back Africa trips for Legado. Thirty-eight years into my life and I was just ready to contemplate motherhood, but thus far the combination of anti-malaria pills and not actually seeing your dad was serving as birth control. France was going to be our first concentrated time together in six months. But within the first hour of sinking my hands and feet into perfect granite cracks high above the Vallee Blanche glacier near Chamonix, I didn't want babies; I wanted more climbing.

I told your dad I wasn't ready, and I knew that at my age it might mean I'd never have kids.

Two weeks later, I got a hole between the pinkie and second toe of my right foot. A hole all the way to the bone filled with crackling, oozy, smelly gunk, created by the simple act of my toes rubbing against each other when stuffed in my climbing shoes and in the mountain boots I wore while hiking to and from the climbs. Nothing sexy, nothing rad. Just a hole. Climbing was out until it got better. Then the rain started. And when, while trapped in the deluge in a twelve-by-twelve apartment in Chamonix, my best friend in New Hampshire called to tell me she had had her second baby, I crumpled to the floor and sobbed. What if I've done my math wrong? I thought.

Is it really worth sacrificing having children to go climbing when one measly hole in your toe can shut down your whole life plan? Does being a mom relate to foot rot? Should they even be in the same equation?

That night, I told your dad I wanted to make a baby. For real.

Two hundred percent. Turns out I was heading here the whole time.

*

Once we started trying to make you for real, it didn't work right away. I cried when I got my period and interpreted my tears like data points on a graph tracking my ever-increasing desire to pursue motherhood. But in hindsight, maybe the tears were just hormones.

We tried again. I took it easy. I decided that if this was going to be my one shot at having a kid, we'd go to the doctor, make sure my uterus was shaped correctly and my tubes were patent. I was ready to get a barrage of tests. Not because I thought we needed them, but because I wanted to be sure. Because, at (by then) age thirty-nine, I wanted to give myself the best shot.

I decided to take it easier, but not count on you appearing in my uterus. So when I got tired on the uphill approaches to climbs, I slowed down. But then when the ice came in on Cannon Mountain in a flash-freezing event, I did one of the earliest-season ascents ever on the Black Dike with my friend Alexa. I led each pitch, and with every tool and crampon placement, I felt my winter body coming alive.

Tap, swing, kick, tap, tap, kick, kick.

That is my music.

I went back to taking it easy the next day, resting instead of climbing, ordering new picks and crampons and putting away my rock-climbing gear to prepare for the frozen season.

I was ready for whatever was to be.

And then on the day I was supposed to call to make an appointment with my OB-GYN, at an exact point in my cycle, I decided for the heck of it to do a pregnancy test. Peter napped on the couch while I peed on the stick. A faint line showed up, which seemed both confusing and significant enough to wake him up.

"I think I may be pregnant," I said.

"How can you be 'maybe' pregnant?" he asked.

I peed on another stick. The same faint line appeared. I Googled it. The internet was in agreement--false positives don't happen, and a faint line is a line. I was pregnant.

I didn't sleep that night. We're doing this, I kept telling myself. By the middle of the night, the we part of my statement was gone--I was doing this. I lay awake in heavy moonlight while Peter slept with seemingly no care in the world. All I could think was if I was the one tipped us over the edge to have children in the first place, then it seemed I would also be the one who carried the dream forward into the future.

*

Every day for that first week of knowing I was pregnant, I spent half the day wondering if we should just put you back. Not actually wanting to go through the steps of having an abortion, but fundamentally feeling like growing a baby (because I didn't then know I was growing two) wasn't what I wanted to be doing anymore. And then the first week dissolved into the second. And the third, and the fourth. And through all those early weeks, the same thoughts kept crossing my mind: I am happy. I am excited. I am on board. I am doing this--but what if we just made a horrible mistake?

A mistake in getting pregnant. A mistake in creating permanence in the form of another being in the middle of marriage--something that, even without kids in the mix, is fraught and imperfect and many times the opposite of permanent.

I don't know anyone who is a parent who is happy in their marriage. I look at the moms and dads I know and the relationships they have . . . and they're awful. I know I'm not supposed to say that. And I am definitely not supposed to write that. I want to find another family we can emulate, but I don't know any. None of you have what I want to have. I am being naive and an ass. I know. I don't have a clue what I'm talking about, standing on this side of the great, raging river of parenthood and marriage.

I told Peter we needed to find a new model. He said he wasn't ready for a minivan. I told him I meant marriage.

December 4, 2015 (Later Still)

Audio Journal | Nine Weeks Pregnant

I'm back on the side of the road ugly-crying. Your dad just texted me that his departure date changed for his trip to climb with his friend Bernd in Patagonia, the alpine-climbing wonderland at the tip of South America. Leaving earlier than I thought next week--thanks again for the support, sweetie! I need to turn off my messages, or get a new husband and friends.

The husband I do have is an internationally certified mountain guide who spends half of his working time training the US military special-forces teams in high angle rescue and mountain mobility and the other half guiding civilians on everything from their first day out to their dream ascents here at home and around the world. And then in his spare time? You guessed it. He climbs. Though you will be part of his spare time soon and part of both of our all-the-times. For now, you're already my all-the-time. But not your dad's . . . yet.

Did you know I was supposed to be climbing in Patagonia this winter? Golden granite, blue ice, and the most perfectly jagged alpine skyline you'll ever know. Even after I saw that faint blue line on the pregnancy test, I thought I'd be able to pull off alpine climbing while pregnant. The only hiccup was that I was tired and nauseous all the time, and I suddenly couldn't quite imagine doing a three-day ascent of a mountain, much less a one-day push, much less a seven-hour approach hike to even get to the climbing.

Three weeks ago, Peter decided to go to Patagonia alone and I told him I would support him. To be fair, we both decided he would go, but only his decision was active. So I used frequent-flier miles from all of those Africa trips and booked myself a trip to Mexico instead. I then spent three days hating him for deciding to actually take me up on my offer to still go to Patagonia, resenting the shit out of him for believing I meant it when I said I would be okay with him going there without me.

I didn't mean what I said. I don't know what I meant.

*

There are people who don't tell anyone they are pregnant until halfway through their pregnancy. I told my climbing-equipment sponsors when I was five weeks along. Of course, back then, I thought I was only telling them about one of you.

I always wake up too early at the Banff Centre Mountain Film Festival. This year was no different, except this time my four a.m. wake-up had to do with nausea instead of jet lag. By 4:15 on my first morning, I had already quested out of my complimentary hotel room in the dark to the Banff Centre gym.

Rowing, squats, chops, Spiderman push-ups. Check, check, check, check. Pull-ups were next and I was already being smart and more conservative, so first I slung my skinny black rubber band around the bar to give me an assist.

I stepped into the band and jumped. But I missed the bar and the tension band shot me backward, depositing me flat on my back on the black floor matting. I erupted into tears first from the surprise, second from the pain, and third from the general emotional shitshow that is being pregnant.

Two things worth noting: not many people go to the gym at 4:15, and Canadians don't believe in providing Kleenex at the gym.

I left the gym shortly thereafter to look for breakfast. My friend and sometimes climbing partner Sarah Hueniken was opening the door to enter the gym as I was rushing out. "I'm pregnant," I said, instead of hello.

Later that day I told my first gear sponsor, testing the waters with an athlete manager who was also a dad.

He was having coffee. I was drinking water, seated in the Maclab Bistro and trying to shift my weight off my bruised backside.

"You're only five weeks though?" he asked.

"I know it's early," I said, "but I'd rather you know why I'm not going to Patagonia this winter . . ." I could not bring myself to also say it might be why I wouldn't be sending him many pictures of me climbing ice for the company's catalog and marketing materials. Back then, I still thought an ice season might be possible.

You had still not made your public debut as my belly dwellers. But I almost announced you one night a few days later in Banff while sitting on a panel celebrating forty years of the festival with five other climbers, among them Tommy Caldwell and Sonnie Trotter. That night the moderator, Ed Douglas, asked them, both dads, what it was like to be a parent and a climber. Tommy and Sonnie gushed about how great it was to be able to climb professionally and travel everywhere with their families.

Ed said something about how incredible it was that they were ushering in a new era in which climber babies could be born and live a vagabond life full of adventure with their families. All I could think was what a bunch of bullshit it was. Neither Tommy nor Sonnie has a wife whose own career is also built around climbing. How does it work then? I wanted to demand. Sarah was on the panel too, but neither of us counted as parents in this conversation--yet. My growing belly strained against my black tights and red dress while I debated announcing why I was so uncomfortable in my clothes and discomfited by this discussion to the twelve-hundred-person audience. But instead I kept you private and promised myself that, when it was time, I'd speak up.

That was three weeks ago. Three days ago, I lay on the ultrasound table while Peter stood next to me and a technician named Mabel scanned my belly. Less than a minute in, she paused the wand and looked away from her computer and directly at me.

"Have you been doing anything special?" she asked. I knew.

"Am I having twins?" I asked. "That's what I see," Mabel said.

I'd like to tell you that the first words out of my mouth were not these, but I have already committed to being honest. "Are you joking?" I asked.

"I don't joke about these kinds of things," Mabel pronounced.

I grabbed your dad's hand and started laughing. I didn't notice the tears until he reached over to wipe them off my cheek. "Babe--" he started to say.

"Only the positive," I interrupted him. "Only the good things."

I haven't slept in the three days since. I research double strollers and tandem nursing instead. "We've got this," I tell your dad whenever I see him. But soon, when he's in Patagonia, I will only have myself to tell.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.